One in Ten Million

Yellow Medicine Dancing Boy was born in Goshen, Connecticut on this day just one year ago. This rare white bison was born on the Mohawk Bison farm of Peter Fay. Not an albino or genetically modified, Yellow Medicine Dancing Boy is believed to be a sign of hope and unity, and some considered his birth and naming ceremony to be sacred events.

Stories of the Lakota people tell that White Buffalo Calf Woman taught them seven sacred rituals and gave them the sacred ceremonial pipe, the Chanunpa. There is a dark side to her story, however, as one of the two scouts who first found her was reduced to a pile of bones when his intentions for the white-clad beauty were revealed as less than pure. The tale of a mortal man overcome by lust for a divine beauty reminds me of “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter” by Robert E. Howard. In the Conan story, the barbarian predictably fares far better than the Lakota scout.

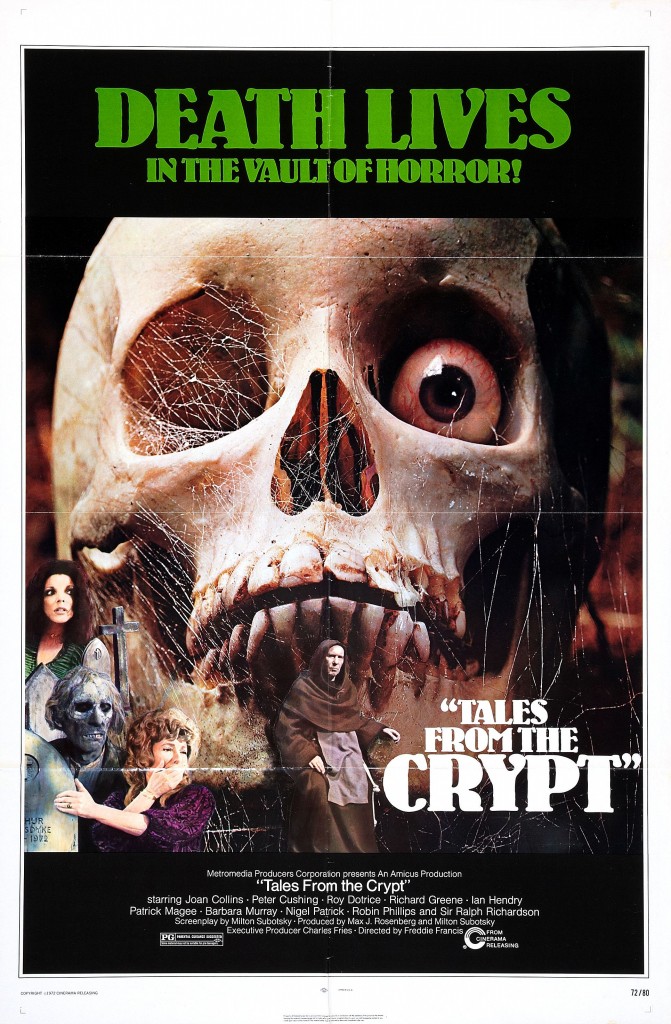

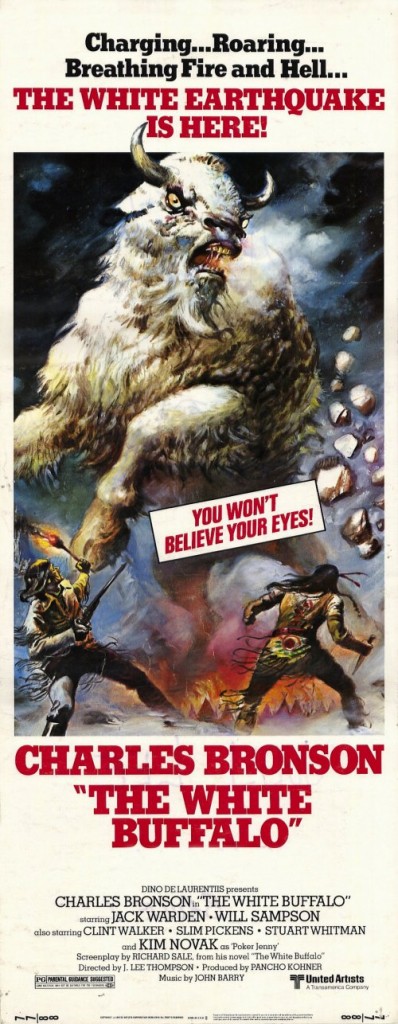

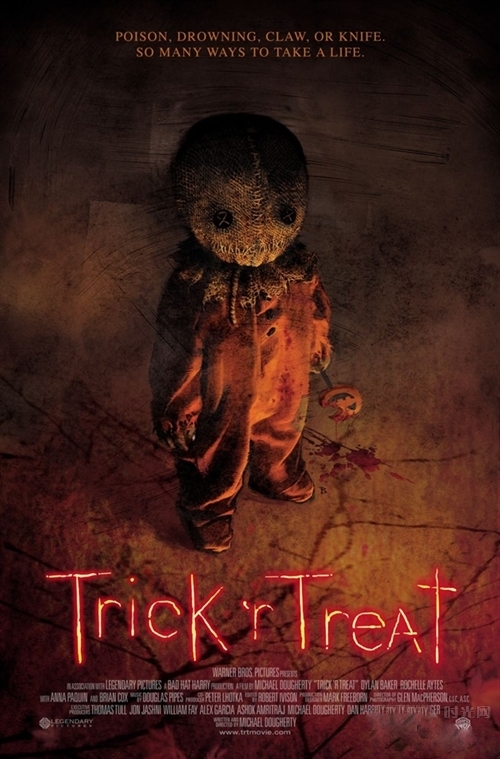

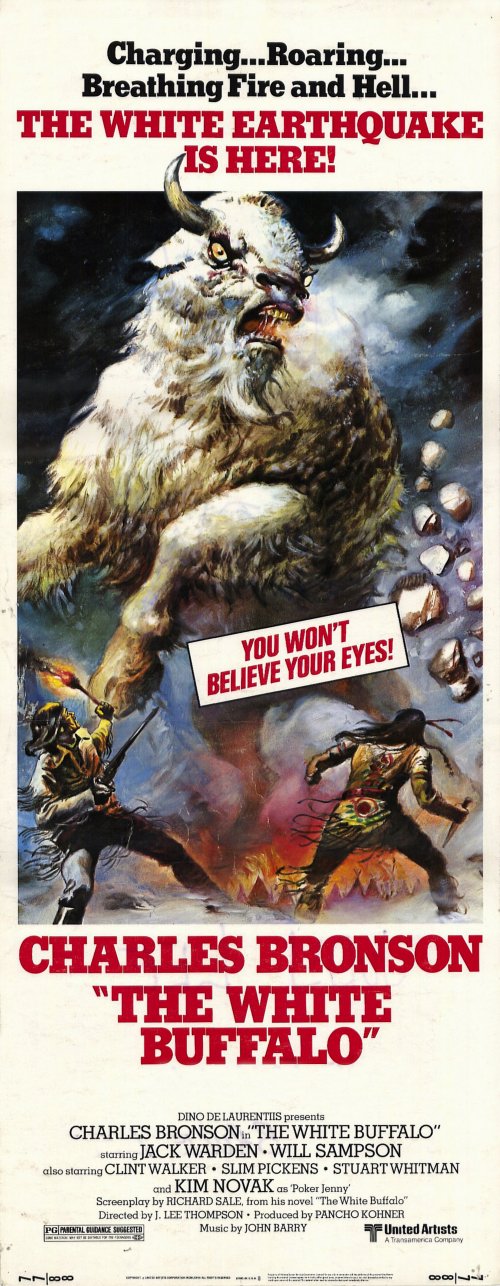

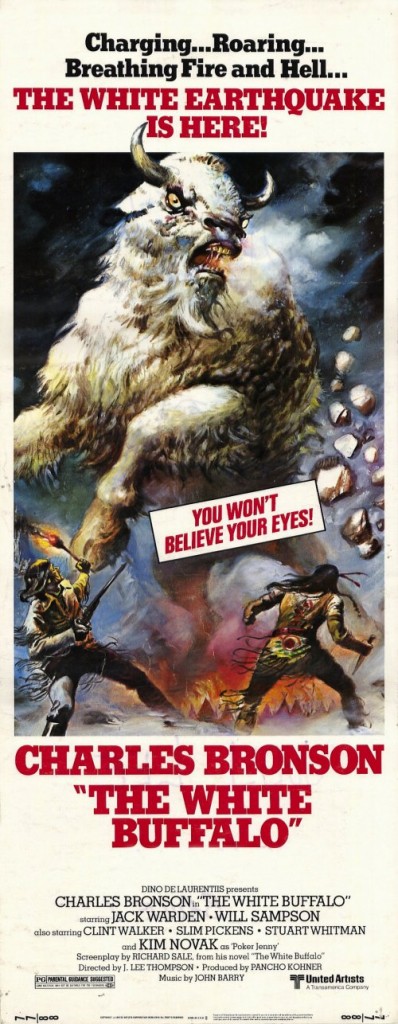

With a screenplay by Richard Sale based on his novel, The White Buffalo (1977) is a strange little western, full of dream-like imagery, dodgy special effects, and genuine frontier gibberish.

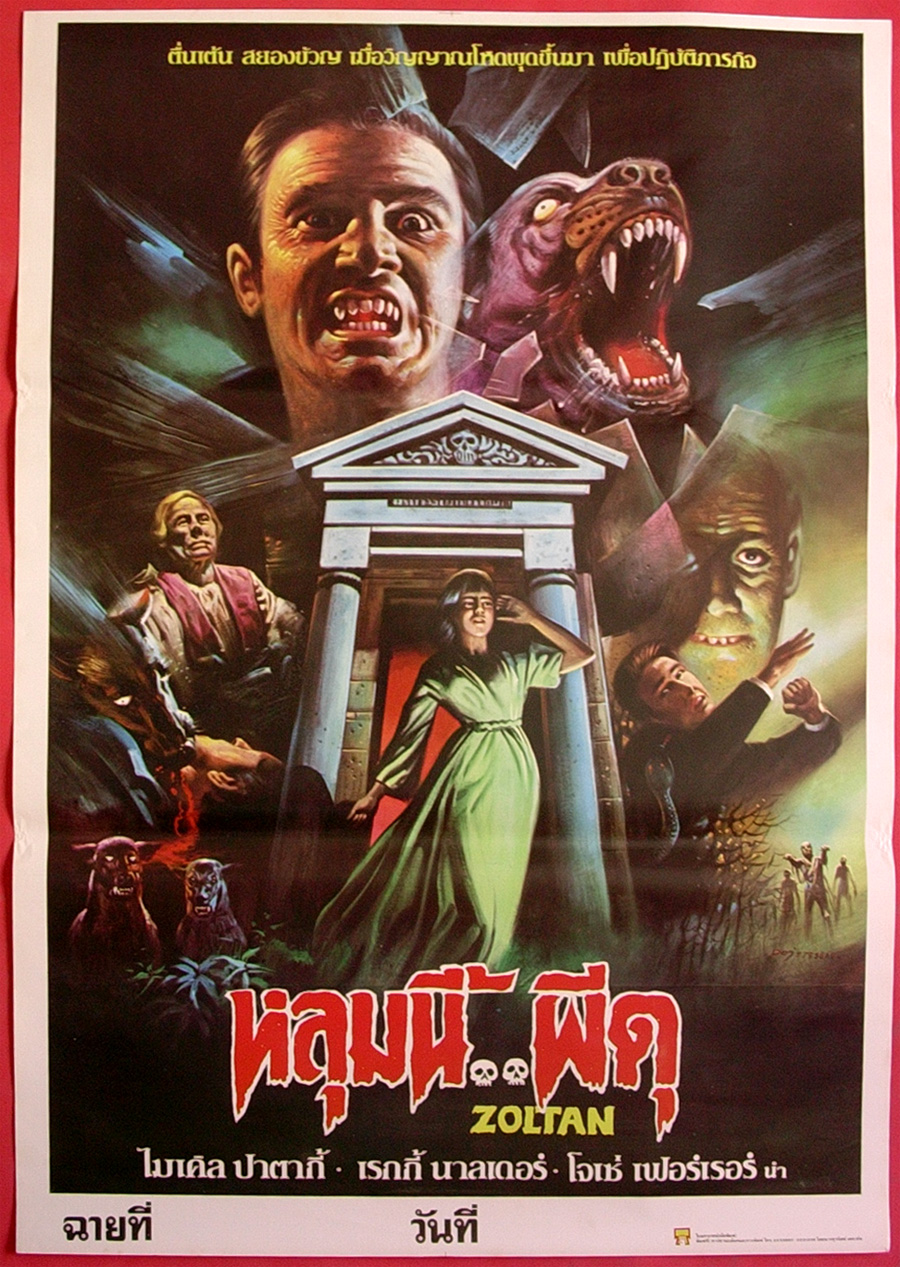

The White Buffalo (1977)

They say the last white spike was put down by “Prairie Dog” Dave Morrow last month way the hell and gone on the Cimarron. Still, James Otis is obsessed with a white buffalo that haunts his dreams, resulting in all manner of flummery. There’s suspicion that James Otis is actually the infamous “Wild” Bill Hickok, but that’s likely just sassafras. In his final western, Charles Bronson plays the haunted man wearing two names, who is in search of the white buffalo that rampages through his nightmares.

Movie Poster for The White Buffalo (1977)

Ridiculous but awesome painting by Boris Vallejo

Our opening credit sequence is set to ominous, ethereal music that, along with the copious amounts of dry ice fog shades of Ridley Scott, helps to set an otherworldly mood. This ain’t no wagon train. Before we meet any of the human cast, we get a good look at our title behemoth, and it’s a mixed bag. Personally, I like the obviously animatronic critter, but some folks will find it laughable. Your mileage may vary.

We soon find it’s all a dream as Hickok wakes with a two-gun barrage that probably puts a few holes in the roof of his train berth. Bill sports slick sunglasses that are likely the byproduct of a “disease of passion”, but we’ll get to that later. Suffice it to say, he’s got problems.

After our brief introduction to Hickok, we get two more opportunities to see the monstrous white buff in action. Mountain man Charlie Zane (Jack Warden) doesn’t see the thing first-hand, but hears its roar and is forced to dodge an avalanche created by it. This scene has all the hallmarks of a traditional western tall tale, the subject of dime novels and American folklore. Zane fares far better than a poor Sioux village that gets utterly (udderly?) ravaged by the angry buffalo for no really good reason.

Crazy Horse, War Chief of the Oglalas, returns too late to prevent the carnage. When he asks “Where is the little one?”, his wife can only reply “She’s gone to the stars.” The normally stoic chief, played with surprising depth by Will Sampson, weeps openly for his dead daughter, but such public displays of emotion are considered unbecoming of a man in his role. For this transgression, he is renamed “Worm” by his father. Worm makes a pilgrimage to the site of his daughter’s burial, Enchanted Mesa, far from the whites and safe from wolves, but he is told her spirit will be tortured until he can avenge her and reclaim his true name.

Charles Bronson in The White Buffalo (1977)

When Hickok arrives in Cheyenne by train, he is astounded by the buffalo graveyard. Killed to make way for the railroad as well as deny game to the Native Americans, the bones are piled high like mounds of white coal. While catching up with an old friend, we find that Hickok’s no friend of the Indians himself, with the Sioux in particular holding a grudge for his killing of Whistler the Peacemaker.

Hickok can’t exactly count many allies on the other side of the law, either. Tom Custer (Ed Lauter) and his cavalrymen are in Cheyenne hunting “Injuns”, relaxing when we meet them in Paddy’s Saloon. As Custer relates it, “Back in Hays City in ’69, Hickok killed my horse from under me and backshot two of my best soldiers.”

Barkeep Paddy recalls differently and insists “Bill never backshot nobody, not in his whole life.”

“You’re looking to wear a marble hat,” threatens Custer, but Paddy is nonplussed.

“You never did give me goosebumps, Tom.”

This exchange and others like it are representative of the style of dialogue employed in The White Buffalo. Fans of True Grit and the HBO series Deadwood (minus the outrageous profanity) should be pretty familiar with the flowery language, but contemporary audiences may be put off. Personally, I can’t get enough of circumlocution.

A Corporal Kileen interrupts this smacktalk session to say Hickok’s on his way to the bar, so Custer and his boys set up an ambush. This set-up goes awry when Paddy reveals his true colors, passing Bill first a revolver then a shotgun so the legendary gunfighter can shoot his way out. Despite their superior numbers, Custer and what’s left of his troop are sent packing. Afterwards, Hickok inquires about “Poker” Jenny, but Paddy claims she’s now known as the Widow Schermerhorn, gone to Fetterman to open her own place. Paddy also warns Bill about the Sioux “riding the Bozeman Trial like Irish banshees.”

Hickok takes a stagecoach to Fetterman, and Slim Pickens has an amusing cameo as the put-upon driver. This sequence serves to illustrate how the world-at-large perceives the persona of Mr. Otis, not knowing that he is actually Hickok. Among the passengers is a foul-mouthed Irishman named Mr. Coxy, who makes the mistake of bringing a knife to a gunfight in trying to rob Hickok. Bill forces him out into the mud and rain at gunpoint. When the stage is assaulted by Worm, Hickok exchanges gunfire with him. Bill hits nothing, but manages to impress the driver who previously thought of Mr. Otis as a “dude”, a “green tenderfoot”, probably on account of his fancy dress.

We’re treated to another cameo as horror icon John Carradine plays Amos the Undertaker in Fetterman. While talking with Pickens’ stage driver, he lets slip that the two dead men in his cart were arguing over a White Buffalo sighting. Bill also learns that an old friend of his is in town, Charlie Zane.

Kim Novak in The White Buffalo (1977)

Bill goes to Schermerhorn’s as James Otis, but “Poker” Jenny (a rare 1970s appearance by Kim Novak) doesn’t recognize him at first. She offers him some coffee, “strong enough to float a colt,” then quickly registers that Mr. Otis not only looks like her old pal “Cat Eyes”, it is him in the flesh.

After some smalltalk, Jenny tries to get down to business, but it seems Bill “ain’t got the gumption,” not even when Jen offers to “fly the eagle.” “One of your scarlet sisters dosed me proper,” he says, implying venereal disease. Widely circulated, it’s of dubious historicity that Bill caught VD, but it certainly fits the haunted man depicted here. Historical accuracy isn’t of paramount importance in this little Wild West fable.

Napping out at Jenny’s place, it’s nightmare time again, and Bill awakes with a start, shooting up the place and decimating some white buff heads. Bill questions why the hell Jenny has such expensive totems, worth an easy $2,000 in gold a piece, but she admits they’re not real and were painted white at her request.

The nightmare beast is very real, however, and Bill knows “If I don’t kill this buff, the dream’ll kill me. Like my own… my own fate is chasing me into the grave.”

Bill meets up with Charlie Zane at a makeshift camp saloon. It isn’t long before Zane tells Bill of his own wide-awake encounter with the white buffalo. Before Bill can get the particulars, “Whistling” Jack Kileen (Clint Walker) and his gang saunter in, all moustache and menace. Bartender Tim Brady offers Mr. Otis $500 in gold to back him against Kileen’s gang as they appear ready to rumble. Brady knows that Jack’s son was the unfortunate Corporal Kileen, shot dead by Otis in the Cheyenne ambush. Thought not called out by name, Martin Kove has a cameo as one of Brady’s men, billed in the credits as Jack McCall. McCall was a notorious buffalo hunter and the man who would later murder Hickok in Deadwood.

Provoked by the young hothead “Kid Jelly”, a shootout ensues in which Hickok kills three of Kileen’s men almost instantly with two Navy Colt revolvers. The patrons are astonished, and word quickly spreads that they’ve just witnessed THE “Wild” Bill Hickok in action. Charlie wants to immediately head out for Deadwood, but Hickok isn’t rattled. He’s not afraid of what was in the saloon, he’s afraid of what’s out there, in the wilderness, in his indeterminate future.

The next morning, Kileen and his remaining men bid Zane and Hickok adieu as they ride out of town. Director J. Lee Thompson treats us to some beautiful outdoor photography, full of snow-capped peaks, verdant pines, and boulder-strewn valleys as opposed to the stagey scenes of the film’s first half.

After a campsite discussion establishes that Hickok hates Indians with a passion reserved for one’s mortal enemies, he and Zane awaken to gunshots, finding themselves surrounded by Crow Indians. Zane quickly points out that they aren’t after them, but a single Lakota instead. Zane admires the lone buck’s bravery, but, at fifteen to one, gives him no chance. Hickok corrects him, “Fifteen to three.”

Once the Absarokee are driven off, a parlay is called between the three victors. Hickok quickly realizes that they’re all after the same white spike, but bids their one-time ally farewell just the same. Later, Hickok thinks he spots his quarry amongst the snowcapped rocks. “Old Timer, shake out a round.”

The gunshot rousts the beast, forcing it to retreat into a mountainside cave. Like a sword and sorcery hero, blazing torch in one hand, revolver in the other, Hickok warily pursues. He finds the buffalo went out another exit, but knows the time ain’t right based upon the details of his dream. “There has to be snow. Heavy snow.”

A mighty roar wakes them from their slumber inside the cave. Outside, Hickok has to put down their gored mare and finds hoofprints leading up across the mountaintop. Hickok tumbles through a carpet of pristine white in a stunning distant shot. Careless in his pursuit, Hickok doesn’t see “Whistling” Jack Kileen, snowshoed, lurking in ambush with two of his men until it is too late. Hickok is forced to take cover behind a ridge and quickly becomes pinned down.

Charles Bronson in The White Buffalo (1977)

The exchange of gunfire is interrupted by the howl of a wolf, and Hickok seems to take particular attention. After Zane takes one the men out with his rifle, Kileen spots what he believes to be the howling wolf, only for the wolf to stand up and riddle him with arrows like Boromir. Dumbstruck, Kileen’s last man stares and gets an arrow in the gut for his trouble. Worm celebrates their victory, but warns the whites that they are in Lakota land, his land.

Hickok invites the Indian to his council. Zane thinks it a clever ruse, but Hickok warns “You try hanging a wooden suit on that child and you’ll answer to me.”

Charlie is aghast. “That snow ossify your brain?” Hickok points out the eagle feather, a chief’s feather. This is no ordinary Indian hunter.

Worm thinks he knows this man, “Okute the Shooter”, the one who killed Whistler the Peacemaker, the murderer called Hickok. Bill claims “The Cheyenne call me Pahaska.” Pahaska was actually a Lakota nickname for “Buffalo” Bill Cody, meaning “long hair”. Instead of being an instance of historical inaccuracy, in the context of the film, it is likely Bill is lying about his identity just as he was under the Mr. Otis moniker.

Worm, having seen Pahaska fight with pistols, offers a long gun looted from Kileen. “Long Hair” reveals that Zane’s long gun is actually his own, forcing Worm to gift the long gun to the suspicious Charlie Zane. Charlie is shamed, and has nothing to offer in return.

“You give me shelter. You share your food.”

Zane eventually gives Worm a knife. Worm seems afraid to touch it. Is he considering how many of his kin it has murdered?

“How is the old one called?” Worm asks.

“Cheyenne call him Ochinee.” Ochinee was actually the name of a Cheyenne subchief killed in the Sand Creek Massacre, but here it is taken to be a metaphorical nickname rather than a literal one, as Ochinee translates to “One Eye”.

“The Great White Warrior of Sand Creek? You speak crookedly. This cannot be true.”

Hickok quickly realizes the disbelief is because Zane has a glass eye. Charlie pops it out, and the superstitious Lakota is taken aback until Hickok calms him by saying Zane is only clowning and that the glass eye is not magic. Worm is about to teach them how to pee (to mark territory like a wolf, a sign the White Buffalo respects) when an avalanche threatens to block them out of their cave.

A debate over who can lay claim to the White Buffalo quickly turns to politics. Hickok offers the classic argument that the land was taken by force from other tribes with lance and tomahawk, not gifted by the Great Spirit. “Today, it’s the white man’s turn.”

Hickok believes resistance is futile. “They are more than the blades of spring grass, more than the buffalo when they smothered the earth in their great herds… You will bend to the long knives or be broken. You will live as they say or die on their bayonets.”

While the two hunters come to an understanding and peace, the old timer is skeptical. The White Buffalo will surely come between them.

In the morning, Zane is surprised Worm didn’t slit their throats. Hickok laments that they didn’t have just one more day of peace. Downhill, they follow the heady scent of buffalo all day until they reach the valley floor of Hickok’s nightmares. And if we didn’t recognize it, the musical cues would fill us in that something dreadful is about to happen just before Hickok flatly spells it out. In his haste, he foolishly ignores Charlie’s suggestion to take the Winchester over the shotgun, which has only one shot left.

The White Buffalo charges for what seems like forever, but it is only a full minute of footage and, yes, the track is clearly visible for the fuzzy white buffalo machine. Just as Charlie warned, the shotgun is, in fact, frozen, so Hickok breaks it over the beast’s dome like a cricket bat.

Worm takes to the high ground, buries an arrow ineffectually in its hump, and then leaps onto its back, stabbing it repeatedly with the same arrow and lasting well longer than PBR regulation 8 seconds. The beast flees with Hickok in hot pursuit unarmed, but all eventually grows still. Hickok helps Worm up and reveals that the beast yet lives and is likely long gone.

The money shot, given away for free in the trailer, is the White Buffalo crashing through a snowdrift to attack. Hickok pulls a Colt from Worm’s belt and empties it into the thing’s head while Worm rushes forward to stab away with an arrow. Afterward, Worm is elated, but Hickok is seemingly saddened to know that he has helped usher in the end of an era.

“Why didn’t you use your gun?” he asks Worm.

“I am War Chief of the Oglalas. I cannot use the White Man’s iron. This bull had to be taken in the old way.”

Hickok correctly identifies Worm as Crazy Horse. Crazy Horse believes he and Hickok are kin, of sorts. Zane wants to backshoot Crazy Horse, but Hickok says no. “The robe belongs to Worm” (meaning the hide).

Zane can’t believe he’d so easily give up $2,000 gold.

“Charlie, I’ll make it up to you in Cheyenne.”

“You can tell your blood brother to shove it up his ass. We’re quits.” Charlie walks away with the gifted long gun, a great symbol for the subsequent treaties between Native Americans and whites.

“You have lost a friend,” Crazy Horse says.

“So it seems.”

“And found one.” Crazy Horse acknowledges that he knows “Long Hair” is Hickok, a great enemy, and while he will tell no one, they must never cross paths again. They bid goodbye to each other, forever.

The epilogue gives birth and death dates for J.B. Hickok (Born 1837, Murdered 1876) and Crazy Horse (Born 1842, Murdered 1877). Hickok was only 39 at the time of his death, but Bronson was 55 at the time of film’s release. Crazy Horse’s birth date is in dispute, putting him at 34 to 37 at the time of his death. Sampson was 43 at the time of film’s release. The choice to cast older actors was certainly a conscious one, to give the impression of men whose time was growing short.

Criticism of the film as a rip-off designed to cash in on Jaws is largely misguided, but producer Dino De Laurentiis did the film no favors during its publicity, putting it in the middle of his killer animal trilogy along with King Kong (1976) and Orca (1977). Even the poster above and trailer below try to shill the film as a monster movie. It is more appropriate to compare both Jaws and The White Buffalo to Moby Dick, the original novel about the hunt for a great white metaphorical beast.

Hickok’s dialogue is the most telling, however, and truly gets to the heart of the matter. “If I don’t kill this buff, the dream’ll kill me. Like my own… my own fate is chasing me into the grave.” The White Buffalo is dying out, and so are men like Hickok and Crazy Horse, killing each other off in the name of progress and civilization. The times they are a-changin’.

“It was hated… and hunted… It was worshipped… and feared…

It was… The White Buffalo”

Though his coat has since turned largely golden brown, Yellow Medicine Dancing Boy will always be considered one of the elusive White Buffalo here at WeirdFlix. Many happy returns. So, take a moment today to give thanks for the wonders of the natural world around us and the diverse people and cultures who inhabit it.