R.I.P. Gene Wilder (1933 – 2016)

Archive for In Memoriam

Time Is a Precious Thing. Never Waste It.

Remembering Jack Kelly

Jack Kelly was born on this date in 1927 to a family already deeply involved in “show business.” Jack’s mother was an actress and model while his father was a theater ticket broker. His older sister, Nancy, would go on to win a Tony Award and an Academy Award nomination.

Jack’s own career began at the age of two, modeling for soap ads, and he made his stage debut at the age of nine. He moved to California with his family in 1938 and went on to attend St. John’s Military Academy and UCLA. His film debut was a very minor role in The Story of Alexander Graham Bell (1939). In 1945, Jack joined the Army and flew on the first B-29 to cross the Arctic Circle.

By 1955, Jack Kelly was already a veteran of radio, stage, and screen, primarily in military or cowboy roles. His Army background made him ideal for the former while the latter led to his most well-known role, but more on that later. Today, we’re going to look at one of those military roles, that of Cpl. Carl Turner in the Universal Studios monster movie Cult of the Cobra.

Cult of the Cobra (1955)

Bolstered by the success of Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), the Universal Monsters had nearly recovered from being made laughable alongside Abbott and Costello. Cult stands as an outlier in a shift for Universal away from supernatural menaces to threats born of science such as the Gill-man and the monsters in It Came from Outer Space (1953), This Island Earth (1955), and Tarantula (1955). While Cult makes a token reference to the speculative science behind the principle of “metamorphosis,” the transformation of woman into cobra is presented as traditional Near East Mysticism rather than a disease (lycanthropy) or a genetic trait. Indeed, the final images of the film only make sense in the context of magic, but that’s perhaps looking at things a little too closely in what is, essentially, a goofy cautionary tale about “Ugly Americans” and the dangers of fraternizing with foreign women.

As Air Force Cpl. Carl Turner, Jack Kelly is perhaps the most ruggedly handsome of the aforementioned “Ugly Americans” and is depicted as quite the ladies man, in both dialogue and in action. He is joined by five others, but the airmen are largely interchangeable in the early proceedings. About to be discharged from service, they’re up for some “wholesome” fun, mostly obsessed with the prospect of female companionship either in their exotic surroundings or back home.

Slender hangs illusion,

fragile the thread to reality.

Always the question: Is it true?

Truth is in the mind and the mind

of man varies with time and place.

The time is 1945.

The place is Asia.

Looking to get a photo op with a snake charmer, “Professor” Paul Able (Richard Long) takes the conversation in a strange direction when he asks “Hey, have you guys ever heard of snakes being changed into people?” The staff sergeant then proceeds to lecture the group on the cult of the lamians and principles of metamorphosis. Paul is a definite buzzkill, but the ham-fisted expository dialogue delivered by Richard Long (House on Haunted Hill) in this scene and the next sets the plot in motion less than three minutes in. The snake charmer, a lamian himself and member of the eponymous “Cult of the Cobra,” is more than happy to sneak the westerners into a cult ceremony for a hundred crisp American dollars.

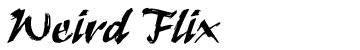

Despite multiple dire warnings, Cpl. Nick Hommel (James Dobson) can’t resist the temptation for a little flash photography. He is instantly caught and the Americans are forced to fight their way out of the temple. The whole sequence, drum-heavy orchestral score and eventual discovery included, is similar to the portrayal of Thulsa Doom’s Cult of Set in pulp classic Conan the Barbarian (1982).

The high priest curses them, proclaiming “One by one, you will die!” The snake charmer also tries to warn them of their unavoidable doom, but his admonishments are cut short by a tulwar to the gut as punishment for his transgressions. I guess he won’t be spending that dirty Benjamin any time soon.

The guys catch up to Nick on the street, finding him unconscious and snake-bit, but still alive. When he awakens in the hospital, he is quick to blame his poor judgment on being rip-roaring drunk, something firmly established in the earlier bar scene. Instead of leaving with his mates the next morning, Nick receives a late night visitor. An unmistakable shadow and point-of-view cobra-cam make his attacker obvious.

Once back in the States, we are reintroduced to the love triangle of Paul Able, his roommate Sgt. Tom Markel (Marshall Thompson), and Julia (Kathleen Hughes). Having made up her mind, Julia breaks it off with Tom at the bowling alley of Cpl. Rico Nardi (David Janssen). Tom takes the news well enough, but the love triangle turns into a love rhombus later that night when he rushes in to “rescue” a shrieking neighbor from an unseen intruder.

After some light flirting, Tom manages to convince his neighbor (Faith Domergue) to allow him to show her more hospitality than the city has thus far in her first week as a New Yorker. She introduces herself as Lisa Moya, but when she accidentally calls him Mr. Markel, she plays it off as having seen it on his mailbox. Serious red flag?

Tom takes Lisa out for her first hot dog and shows her the sights. She doesn’t drink, smoke, or kiss, and seems to rankle every animal they encounter, from cats to Tom and Paul’s dog, to carriage horses on the street. More red flags, but Tom is enchanted by this exotic mystery woman from across the hall.

After their day on the town, Tom insists on introducing Lisa to his roommate Paul. Lisa picks up a framed photograph of the six uniformed soldiers and inquires about each of them in turn.

If the relationship between roommates Tom and Paul is awkward and tense, that’s nothing compared to horndog Carl just openly hitting on his supposed buddy’s new girl shortly after meeting her. Jack Kelly manages to ooze oily swagger as he lays on the charm. His unwelcome attention earns him a crack across the jaw from a jealous Tom.

Soon, Tom’s Air Force buddies start getting eliminated in a series of cobra-cam sequences, one by one, just as the priest had promised. There’s a surprisingly solid stunt with a car flipping over during one of the attacks. Can “Professor” Paul Able and his remaining fellows uncover the truth behind these sudden deaths before it is too late?

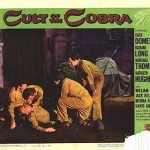

Promotional Photo of Faith Domergue as

Lisa Moya and her cobra alter ego from

Cult of the Cobra (1955)

Cult of the Cobra was the first of four genre films for Domergue released over four consecutive months in 1955 (along with This Island Earth, It Came from Beneath the Sea, and The Atomic Man).

As Lisa Moya, Domergue is cleverly lit in an almost noirish style. Her large, dark eyes are framed by light, leaving the rest of her head and shoulders shrouded in deep shadow, suggesting the hood of a cobra. It proves very effective and helps rescue the film from the noticeable absence of a signature transformation sequence as seen in such earlier Universal Monsters films as The Wolf Man (1941) and even Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1953).

Later the same year, Universal reunited Jack Kelly with Marshall Thompson and David Janssen as soldiers for the epic Audie Murphy bio pic To Hell and Back. The war film set a box office record for Universal that stood for nearly two decades. This record was eventually beaten by a low budget monster movie plagued with production troubles known as Jaws (1975).

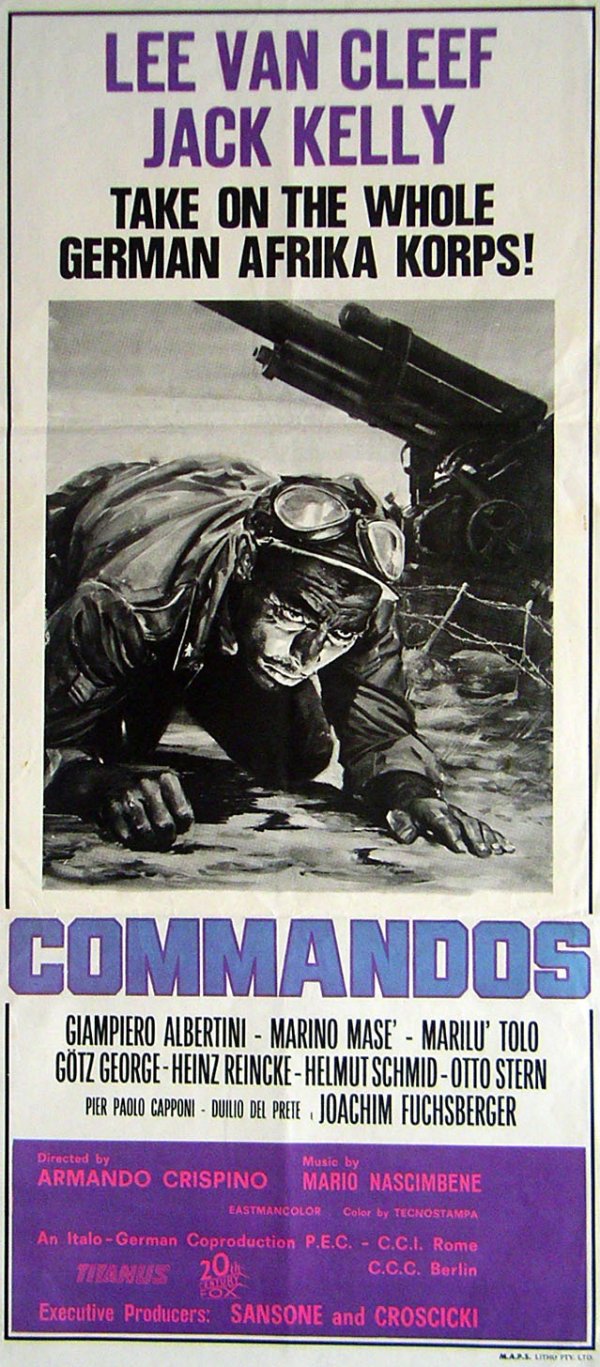

Jack Kelly continued to play soldiers and cowboys for much of his career, including the role of Captain Valli in one of my favorite macaroni combat films, Commandos (1968). His most iconic role is undoubtedly that of cowboy gambler Bart Maverick (brother to James Garner’s Bret). Beloved Bart would also be Jack’s final role, appearing in the NBC television movie The Gambler Returns: The Luck of the Draw (1991) just a year before his death from a stroke.

With appearances in such diverse genre fare as the classic Forbidden Planet (1956), Kurt Neumann’s She Devil (1957), and The Human Tornado (1976), this is surely not the last time we’ll discuss Jack’s career. We hope you’ll return as well the next time we remember the work of Jack Kelly.

Scream If You Believe In… The Tingler!

William Castle was born William Schloss, Jr. in New York City on this date in 1914. Schloss took the stage name Castle (translating “Schloss” from German to English) when he made his Broadway debut in 1922. At age 13, William was mesmerized by the Prince of Darkness himself, Dracula, played on Broadway by Bela Lugosi, just a few years before Bela reprised the role on film for Universal. On Lugosi’s recommendation, William Castle was given a job as an assistant stage manager, causing Castle to drop out of high school.

By 1941, Castle had acquired a knack for creative misrepresentation, having already posed as the nephew of famed Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn during his teenage years. With Orson Welles leaving his renowned Stony Creek Theatre in Connecticut to make Citizen Kane (1941), Castle seized upon the opportunity and convinced Welles to lease him the theater. Castle’s leading lady was the Berlin-born Ellen Schwanneke, but theater guild regulations dictated that German-born actors could only appear in plays originally performed in Germany. Castle responded by immediately conjuring up a fictional German play, Das ist nicht für Kinder (Not for Children). Ellen Schwanneke was invited to return to Germany by the Nazis, and this further fueled Castle’s hype machine. Promoting Schwanneke as “The Girl Who Said No to Hitler,” Castle used the telegram refusal as a press release of sorts. He even went so far as to secretly vandalize the outside of his own theater with swastikas to create additional controversy.

It was the first of what would become William Castle’s enduring legacy, promotional gimmicks that were often more memorable than the film they were designed to shill.

The Tingler (1959)

The gimmick at work in William Castle’s The Tingler is Percepto, a 4D film experience provided by $250,000 worth of surplus WWII airplane wing deicing motors. These were affixed to the undersides of seats scattered throughout the theater. At an appropriate moment in the film’s climactic sequence, the screen would go black and these motors would buzz, eliciting screams from startled patrons in the gimmicked seats.

The Tingler is the third of five collaborations between screenwriter Robb White and director/producer William Castle, following Macabre (1958) and House on Haunted Hill (1959). White was a world traveler, a pilot in WWII, and a prolific writer, leaving his engineering job with DuPont after selling his first story for $100. Of his 24 published novels, only one remains in print, the Edgar Award-winning Deathwatch (adapted for ABC television in 1974 as Savages).

So, what is a “Tingler?” Well, according to Dr. Warren Chapin (Vincent Price), the Tingler is a parasite that lives at the base of the human spine, feeding upon fear. If it grows too large, unabated, it will eventually crush your vertebrae, providing a physical justification for death by fright. Screaming relieves some of this tension and causes the creature to relent. This is, admittedly, questionable science at best, and probably more appropriate to a Frankenstein film set in the Victorian era than in the late 1950s, but we’re not exactly talking Watch Mr. Wizard here. This is just a couple years after The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) proposed that the heart is composed of one big cell. I guess movie-goers weren’t exactly up on grade school anatomy back then or they just cared a lot less about such inaccuracies.

For a film with such a hokey sci-fi premise, The Tingler manages to pack in quite a bit of subtext without being preachy or ham-handed. The most obvious juxtaposition in the film is the thin veil between the rational and the irrational, a line easily blurred by drugs, madness, or both. When Chapin is stymied by his inability to frighten himself, he resorts to LSD, providing the first depiction of acid use in a major motion picture. The resulting experience is surprisingly restrained, largely conveyed by the often underrated acting talent of Vincent Price. One can only imagine the gonzo directorial choices of a Dario Argento, Terry Gilliam, or David Lynch.

A particularly stylish demonstration of the irrational is accomplished by filming one of the signature scenes in color. A bathtub filled with garish red blood sits in striking contrast to a set painted in gray tones and an actress covered in ashen make-up to match. The visual effect is surprisingly seamless.

This use of color also highlights another of the movie’s main themes, that of changes in the film industry itself. Oliver and Martha Higgins (Philip Coolidge and Judith Evelyn) are the owners of a struggling revival theatre that shows silent films. Oliver seems to speak from William Castle’s own heart when he pines that “Some of these old silents are just as good as the movies they make nowadays even though the sound and the color and the screen’s a block wide.”

Chapin’s source of wealth involves another of the film’s themes, that of class divide. Chapin’s laboratory and research are funded by his father-in-law, as his unfaithful wife, Isabel (Patricia Cutts), is all to quick to remind him. Isabel cuckolds him with a heartless bravado more commonly seen in film noir. Cutts is delightfully vampish as the spoiled daddy’s girl. Check her out in the lusciously lurid red dress to the left.

Pamela Lincoln and Darryl Hickman round out the cast as Lucy Stevens and David Morris, Chapin’s sister-in-law and research partner, respectively. An accomplished child actor, Hickman had well over a hundred credits to his name before being recruited by Castle to play Lucy’s fiancé in the film. Reluctant at first, Hickman was convinced by Castle that it would help his real life fiancé’s career. Darryl even declined his salary for the role. Sharing scenes as a fellow pathologist alongside Price’s Dr. Chapin, Hickman was forced to wear lifts to bridge the gap between his 5’10″ height and Vincent Price’s towering 6’4″ frame.

The climax of the film takes place in the revival theatre, during a surprisingly packed showing of the silent film Tol’able David (1921). This provides a great opportunity for the film to build suspense without dialogue while the tingler makes its way through the unsuspecting audience in search of a prospective victim. The film comes close to breaking the fourth wall as the screen goes black when Dr. Chapin cuts the power. For theatrical premieres, a fainting woman (in actuality a planted shill) is taken out of the audience on a stretcher. After some verbal reassurances from Chapin to the in-film audience (which serves double duty as Price reassuring the “real world” audience), our film resumes for the grand finale.

The Percepto gimmick made quite the impression on many theater-goers. In his youth, cult film director John Waters would seek out a rigged seat to get the full effect while viewing. “Rumble-Rama” in the film Matinee (1993) and the character of Lawrence Woolsey (John Goodman) are clearly based on Castle and his ambitious promotional style.

Even without the dubious benefits of Percepto, The Tingler is a fun little monster movie, well worth your time. For this and his many other contributions to genre film, we give heartfelt thanks to William Castle. He was certainly one of a kind.

R.I.P. Michael Ansara

I recently rediscovered Mr. Ansara’s work with the two films I selected to feature as part of the William Castle Blogathon. His performances in both films were highlights I felt compelled to point out. I was saddened to learn of his passing this past Wednesday.

I’m not going to offer a career overview here and now, and such things are easily found elsewhere. Undoubtedly, we will look at his impressive career in genre films time and again, and I hope that will do some small measure to help insure he is not forgotten. I guess, with this short, woefully insufficient post, I just want to say “Thank you” to a man who brought so many fond memories to my childhood and continues to amuse and inspire me as an adult writing about film.

Michael Ansara (April 15, 1922 – July 31, 2013)

“We’re all human. We have our foibles, we’ve made mistakes and yet there is still greatness.” — Michael Ansara

Castle and Crusader

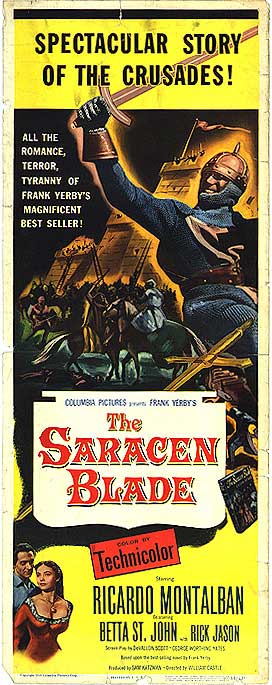

He convinced you that the luxurious Chrysler Cordoba (priced at $5,580) was upholstered in “soft Corinthian leather“. As Mr. Roarke, he offered to sell you your fondest wish for a mere $50,000. And as Khan Noonien Singh, he taught you the best way to serve up revenge. But long before all that, way back in the halcyon days of 1954, Ricardo Montalbán showed what it meant to love, lose, endure, and avenge. He was Pietro Donati. He was The Saracen Blade.

This film forms our second entry in The William Castle Blogathon, graciously hosted by The Last Drive In and Goregirl’s Dungeon. Directed by William Castle from a screenplay co-written by DeVallon Scott and based on the Frank Yerby novel, The Saracen Blade (1954) was the last of four collaborations between Castle and Scott (along with Conquest of Cochise (1953), Slaves of Babylon (1953), and The Iron Glove (1954)).

Frank Yerby was the first African-American writer to become a millionaire from his work and the first to have a novel purchased by Hollywood for a film adaptation, The Foxes of Harrow (1947) starring Rex Harrison. His painstakingly researched historical romances covered a multitude of time periods. In 1952, the year of The Saracen Blade‘s publication, Yerby expatriated to Europe, citing the specter of racism as his rationale.

The Saracen Blade is the last of three film adaptations of Yerby’s novels, following The Foxes of Harrow (1947) and The Golden Hawk (1952).

Ricardo Montalbán stars as Pietro Donati. Montalbán got his start in acting in 1941 by appearing in dozens of three-minute musicals for the Soundies film jukeboxes, precursors to the modern music video. Arriving in Hollywood in 1943, studios wanted to Americanize his name into “Ricky Martin”. With a leading role in the Mexico-themed film noir Border Incident (1949), he became the first Hispanic actor to appear on the front cover of Life magazine. Many of his early roles were as an “Indian” in westerns or as a “Latin Lover”, but as Pietro, he gets to show his action/adventure chops.

Pietro’s father, the elder Donati, is played by Frank Pulaski. Pulaski served as a liaison between the U.S. Army and the Australian 7th Division during WWII. After the war, he took up acting, playing the tribune Quintus uncredited in The Robe (1953). Changing his name to Guy Prescott after The Saracen Blade, he appeared in another Crusades-era film as an uncredited Arab in King Richard and the Crusaders (1954).

Nelson Leigh had been acting for over a decade before taking on the role of Pietro’s mentor and foster father, Isaac. Along with his fair share of adventure films and westerns, Leigh made a career of playing father figures, from Jor-El in the Columbia Pictures Superman serial (1948) to King Arthur in The Adventures of Sir Galahad (1949). He is perhaps best known for playing Mars Mission Commander Dr. Eldon Galbraithe in the sci-fi thriller World Without End (1956).

William Castle regular Michael Ansara once again threatens to steal the show as Count Alesandro Siniscola, Pietro’s main antagonist. Ansara appeared in an earlier Frank Yerby adaptation by producer Sam Katzman, The Golden Hawk (1952). The Saracen Blade was the fourth of five films Ansara did with William Castle at the helm. They would part ways soon thereafter with Ansara transitioning from westerns and Biblical epics to television and Castle entering his schlock and shock phase.

Betta St. John, born Betty Jean Striegler, plays Pietro’s one true love, Lady Iolanthe Rogliano. As Striegler, she made her film debut at the age of ten, singing in Destry Rides Again (1939). After performing on Broadway in Carousel and South Pacific (part of the original cast in the latter), she appeared in The Robe (1953). She is perhaps best known for her role in the proto-Amicus horror film The City of the Dead (1961) shortly before her retirement.

Carolyn Jones plays her foil, Lady Elaine Siniscola, a far cry from her role as victim-turned-exhibit in House of Wax (1953) the year before. While she makes a fine blonde femme fatale, her striking, batrachian eyes would serve her better as the iconic Morticia on the long-running sitcom The Addams Family. Shortly before her death from cancer, she re-teamed with Montalbán as four different characters on four different episodes of Fantasy Island.

The Saracen Blade (1954)

The year is 1194. In a public square in Iesi, Italy, a crowd waits with bated breath for the birth of Frederick II, Emperor of all Europe. Amongst the onlookers are the blacksmith Donati and his friend Isaac. Isaac explains the dual need for security and transparency to prevent the noble child or his lineage from being compromised.

Bells ring to announce the birth of the Empress’ son. Shortly thereafter, Donati’s own wife, Maria (Nira Monsour), starts going into labor. Panicked, Donati asks a guard to fetch one of the Empress’ midwives. Midwife Gina (Poppy del Vando) besmirches Donati and all other men as useless at such times, calmly escorting Maria away.

After giving birth to Pietro, Maria is stricken with fever. Isaac offers to fetch a man who might be able to help, and Donati insists upon accompanying him. They run afoul of Count Siniscola, called “Count Satan” by Donati in ill-timed mockery. Siniscola, like Isaac earlier but not nearly as gently, takes exception to Donati’s newfound pacifism. He claims the blacksmith ended his vassalage early, and the lack of swords cost him in his feud against Baron Rogliano. Siniscola’s men take Donati into custody by force.

By the time Isaac returns to Maria, she is already dead. With the father captured by Count Siniscola, Isaac offers to raise the newborn son. While Frederick II sits the throne in Rome, receiving tribute from the distant corners of the Holy Roman Empire, humble Pietro Donati grows up in Sicily.

There, we find him dueling with his friend Afghal. Using a trip to turn the tables on his sparring partner, Pietro defeats him in good humor. Afghal wants Pietro to join the Saracens, but Isaac has raised him as a Christian.

Isaac calls Pietro away from his tomfoolery to tell him about a revolt in Count Siniscola’s territory, led by his father. They take a ship to mainland Italy, and we’re treated to some poorly integrated siege footage, tinted from the black-and-white Prince of Foxes (1949). The siege, as depicted, takes place at night while Isaac and Pietro talk and look on from horseback in full daylight. Not sure if they planned to film an actual siege here and the budget fell short or if the planned stock footage was switched unexpectedly or if no one gave it that much thought.

The elder Donati has been captured and Isaac immediately considers ransoming his friend. “The arm of Hercules himself cannot help your father now, my boy, but there is still one power on this Earth that can… Gold. Let’s pray we put away enough of it.”

With the blessing of the Siniscolas (Alesandro and his son Enzio (Rick Jason)) paid for in gold, Pietro approaches the castle to parlay with his father. The rebels reluctantly pull him over the battlements on a rope. Father and son are reunited, and Pietro is eager to fight by his father’s side, not discouraged by the notion that they are all doomed men. When he presses the issue, the elder Donati saves his life by knocking him out with one right hook across his glass jaw.

When Pietro awakens outside the castle walls, he finds that the Siniscolas beat him to betrayal and have hanged Isaac (check out Pietro “Tebowing” in Lobby Card 2, below). He overhears Baron Rogliano (Edgar Barrier) and his daughter Iolanthe tut-tutting about the carnage, vowing to see the Siniscolas repaid in kind one day. Pietro begs to join the lord’s service, giving his curriculum vitae, but the baron is dubious. “For if you are so gifted, why do you seek service? I should think it would seek you.” Based purely on his claims, Iolanthe recommends him.

Pietro proves to be skilled with mace as well as quill, but is visibly smitten with the Lady Iolanthe. While he keeps the records, she flirts with him a bit, questioning his dedication to skill at arms and his thirst for vengeance. “By the stars in heaven, Iolanthe, if you stay I’ll forget I hate the Siniscolas for the rest of time I have nothing in my heart but you. Is that what you want me to do?” This is delivered as a run-on sentence, awkward but strangely sincere.

“What’s the matter?” she asks.

“With you, nothing, Iolanthe, but I could easily be hanged for this, and you banished to a convent.”

She wants to elope with him, but he has made a vow to her father and cannot violate that, not even for her.

The Siniscolas arrive at that very moment to forge an alliance, shocking Pietro. Baron Rogliano sends for Lady Iolanthe, and Pietro urges her to “smile sweetly for your guests.” Late that night, Baron Rogliano wakes his daughter to deliver the good news. She is to wed Enzio Siniscola and become a countess. His grandson will be heir to the combined Rogliano and Siniscola holdings. After he leaves, she weeps into her pillow.

The Lady Elaine of Siniscola tries to grill Iolanthe on her true feelings, speaking ill of her own kinsman Enzio. Elaine demands a guided tour of the castle and accuses Iolanthe of hiding Pietro when they stumble upon him hard at work.

“He’s a young man, that’s always of interest. I wonder why it took us so long to come upon him. The castle records are usually kept by a… a weezened (sic) oldster with a gray beard.” She is charmed by his wit and easily detects the sexual tension between him and Iolanthe, but he warns that they should not be so familiar with one about to marry Enzio Siniscola. When he confesses his father was a blacksmith, she loses interest in someone so low-born.

That night, Enzio finds his bride-to-be in the gardens brooding. He kisses her and worries he has offended her. Enzio asks if he has a rival, while Pietro looks on from hiding. When Enzio leaves to fetch her scarf, Pietro asks Iolanthe to elope with him. Enzio returns to find her gone.

The young lovers ride through the night, but Iolanthe’s horse eventually tires out. This is the infamous moment when Montalbán bends down and gets his scabbard stuck in the dirt. Castle and company just roll with it. Extra takes cost money. Pietro and Iolanthe give the horses a rest and wander the river bank together.

Pietro grows discouraged. “You will never be the wife of a count, or a baron, or even a knight.”

“But I’ll be your wife, and I’ll be very happy.”

“You will go without many things.”

“But not without you. We’ll starve together. What’s it like to starve, Pietro?”

“I have no intention of finding out, even if it’s with you.”

They are soon found and surrounded by riders led by Enzio. He leaves the decision of Pietro’s fate to Iolanthe, but only after they are wed. After said nuptials, Enzio looks in on Pietro’s cell. The jailer confirms that only the Lady Iolanthe comes to visit him, every day at the break of dawn. Enzio instructs that the jailer will be asleep when she arrives tomorrow. The jailer fears that she will steal his keys and free the prisoner, but that is just what Enzio is counting on.

Emperor Frederick II (Whitfield Connor) has come to visit, and there’s a subtle nod to his legendary falconry skills. Clearly disappointed, he is promised better game for hunting by the Siniscolas. “Cleverer than any stag… faster than even the boar… one seldom hunted.” Shrewd though the emperor may be, he has clearly never read “The Most Dangerous Game”, but that’ll be published about seven hundred years hence, so I suppose I’m expecting too much. Yerby was undoubtedly familiar with the classic short story.

Iolanthe does as anticipated and frees Pietro with the stolen keyes. She implores Pietro to hurry without her, lest she slow him down and he be recaught. Enzio finds Iolanthe closing the cell door and boasts about their upcoming hunt, happy that she has decided his fate as promised.

Pietro flees the hunting hounds through the forest until they tree him like a cat. While they tear his coat to shreds, he drops down and runs away. Coming upon the Lady Elaine, he wades through tall reeds to cross the stream and sneak up behind her, hoping to steal her horse. The riders approach, and he is forced to threaten her with a dagger to insure her silence. Despite her disdain, they quickly get to flirting.

“To think, my cousin Iolanthe has probably given you her lips.”

“So? They’re her lips…”

“I only wonder how she ever made them clean again.”

He kisses her passionately. “Try soap, try perfume, and then try pumice stone and sanding paper. Good day, milady.”

He mounts her horse and rides off as she is left to smile guiltily.

With Frederick II approaching, Pietro dismounts to hide in the thick brush. Still, the Emperor nearly spears him. They exchange words, but before things can be sorted out, Pietro kills an attacking boar with the thrown spear, saving the Emperor’s life. Pietro tells him the circumstances of his birth and their strange parallel lives. “Born in the same hour? We shall probably die in the same hour…”

Frederick II is impressed with Pietro, but not his thirst for bloody vengeance. With Frederick’s inspiration, Pietro asks for Lady Elaine’s hand in marriage, an oblique angle from which to launch his plot for revenge. Emperor Frederick II introduces the Siniscolas to a man held in highest regard, soon to be knighted upon his return from the Holy Land and then to inherit the first barony that falls vacant. It is, of course, Pietro, and Frederick savors the look of disgust on the faces of the Siniscolas.

The Siniscolas call a family meeting where Lady Elaine instructs her kin to mind their manners while she, unafraid of Pietro, gets close to him to discover his plot. This backfires when Pietro asks Lady Elaine to marry him, leaving her practically speechless. Frederick II plays matchmaker, and the two men make light sport of Lady Elaine’s discomfort. When her cousin, Count Siniscola enters, Frederick is excited to deliver the news, but Lady Iolanthe trails behind, and her disdain wounds Pietro and puts doubt into his plan.

On their wedding night, Elaine is beyond reluctant.

“A kiss is one thing even an Emperor can’t make me give you. What, do you have him with you now, dear husband? Is he nearby where you can call on him for help?”

“From now on, I need very little help. Very little…”

He kisses her forcefully, and she pulls him even closer. He lays her down on the bed as she gazes up longingly into his eyes, fluffs her pillow, and leaves, satisfied with his skill at frustrating her expectations. I’m surprised she didn’t throw something at him.

Later, she sees him off to the Crusades.

“Crusaders always write home, and their wives always say prayers for the husband’s safe return. You too, I’m sure, will say a little prayer each day that… uh, I do not come back?”

“I suppose the next request is that I’m faithful to you while you’re gone?”

“You know the kind of man I am. I never ask the impossible of anyone.”

The moment he’s gone, she cozies up to Alesandro, who acknowledges the church’s reluctance to let the two cousins marry. This is our first inkling that there’s clearly some history between the two. Enzio walks in on them to tell that he and Alesandro must join Emperor Frederick on his Holy Crusade. Alesandro is not frightened, and sees this as a welcome opportunity.

“What will happen to me, I cannot say, but one thing I can assure you, your Pietro will not return to you.”

Elaine is strangely charmed. “This jealousy becomes you, Alesandro.” They embrace and kiss.

While Alesandro believes Frederick’s decree is Pietro’s doing, Frederick tells Pietro he needs the Siniscola’s men and that Pietro must confine his fighting to the Saracens. Pietro acquits himself well, and on the field of battle, he saves Emperor Frederick II from a Saracen. He is subsequently knighted for his bravery.

An unnamed prince (Gene Darcy) needs volunteers for a suicidal force to hold the Turks back while the others, including the Emperor escape. Count Siniscola volunteers himself and his son first, then goads Sir Pietro Di Donati into volunteering as well. The prince finds the Siniscolas too elder in knightly service, and they feign disappointment.

“You cannot ask a better death, Sir Pietro, than to die fighting for your emperor and the Holy Sepulchre.”

Pietro is defeated by the Turks and taken as a slave. Enraged by a taskmaster whipping a woman, he wrestles the man to the ground. He is immediately confronted by an Arab who questions his concern and shows that the woman, Zenobia (Pamela Duncan), is being punished for the gouges inflicted on his cheek. Pietro mocks Haroun (Leonard Penn), whose pride is as wounded as his face. Haroun offers to let him take the remainder of the whipping in her stead, and he agrees. Afterwards, Zenobia lovingly tends Pietro’s wounds.

Pietro’s repeated escape attempts, and resultant floggings, tax Haroun’s patience. “If I can’t get value from you as a slave, at least I’ll make an example of you to the others. One more try and you’ll be put to death. Twenty lashes don’t do any good? Give him thirty!”

Zenobia hopes to buy Pietro’s freedom with some jewelry she has acquired (gifts from admirers, perhaps?), but confesses she wants her own freedom as well. Haroun claims her own value highly exceeds that of the Italian. At knife-point, she makes him swear on the Koran (pronounced “Korrin”) that they will be allowed to go.

Meanwhile, the church has granted Count Siniscola permission to marry Lady Elaine, but Emperor Frederick II reminds him that in cases of doubt, the wife should wait seven years for her husband to return. He does concede that he has promised Pietro a barony, but that it shall be the Barony of Rogliano, which Alesandro believes belongs to him by Enzio’s marriage to Lady Iolanthe. Emperor Frederick II has found question in the lineage of Lady Iolanthe’s father, making the barony vacant.

When Count Siniscola returns home, he finds everyone else in ill humor except for Lady Iolanthe. Word has arrived that Baron Pietro of Rogliano is returning home with a Saracen girl. “She wears a veil after the manner of Moslim women.” Lady Elaine tries to share her annoyance by taunting Lady Iolanthe about this prize.

On the evening of his return, Pietro is surprised to find Lady Elaine smiling at him. She tries to charm him, but he sees through to her naked avarice after his newly bestowed title and fortune. After Pietro departs, Count Siniscola confronts her, dagger in hand, and demands that she use it to murder her husband, but she believes she could be very happy with Pietro.

“My position as a baron’s wife leaves very little to be desired. He has wealth. Ooh, not as great as yours, but very near. He stands high in the Emperor’s favor. Those are the cold facts. I see no reason not to face them. Then, consider that he has a certain grace and charm about him, even comparable with yours, cousin. In strength, Pietro is your equal. In age, he’s a much younger man, and from my point of view, superior.”

Alesandro pulls her close, kisses her, and thrusts the dagger into her heart.

Despite Elaine’s flaws, Pietro mourns her loss. He declares war on the Siniscolas. In the heat of battle, Lady Iolanthe warns Pietro that Frederick has decreed that he will pay with his life if he kills the Siniscolas.

Enzio prepares to spear Pietro in the back while he is distracted by Lady Iolanthe’s words, but Pietro’s loyal retainer Giuseppe (Edward Coch) saves him with a well-aimed crossbow. Count Siniscola quickly descends the battlements to engage Pietro in a final swordfight amidst smoke and flame.

Both men lose their shields in turn, with Alesandro nearly proving too skilled for Pietro. Count Siniscola uses the trip maneuver Pietro demonstrated earlier in the film against his buddy Afghal, but Pietro has a counter, and while on his back, as the Count moves in for the kill, Pietro plunges his sword into his foe’s stomach, killing him.

Pietro bravely accepts the punishment for his actions from the Emperor. “Even for you, I cannot make exception in matters of this kind. You must pay for your presumption. Pietro Donati, your lands and titles are hereby taken from you. What was yours when we first saw you, your life, we leave you, but nothing more.”

“I’m still rich, sire. I have my life, my love, and your friendship.”

Pietro and Lady Iolanthe depart for Venice to start again… together.

The End.

Click on the banner above for more of “The William Castle Blogathon” hosted by The Last Drive In & Goregirl’s Dungeon (July 29 – Aug. 2, 2013)

Reviews of The Saracen Blade, even contemporary to the film, tend to focus upon its low budget and often misrepresent or misunderstand key plot points. Admittedly, the battle scenes, when not composed of awkwardly inserted stock footage, rarely depict more than a dozen combatants in frame. There is also very little of the sweeping landscapes of Europe or the Holy Land, and the whole production could have been filmed in a good sized backyard. Indeed, the interiors were all shot on several sound stages near downtown Los Angeles.

Still, the costumes are appealing and the dialogue is fun, even if the line deliveries are occasionally specious (“weezened”, “Korrin”, “Moslim”). None of the actors come across as openly contemptuous of the material, and everyone seems to be giving their best effort. I believe, given a proper budget, Castle and cast could have delivered an adventure classic. Alas, such was not to be, and The Saracen Blade must stand as a footnote to a number of celebrated careers. It’s solid B-movie fare, but, at the end of the day, that’s an accomplishment in its own right.

Someday, I’ll probably check out the other two William Castle/DeVallon Scott collaborations (Conquest of Cochise (1953) and The Iron Glove (1954)). Hopefully, you’ve enjoyed my humble contributions to The William Castle Blogathon, hosted by The Last Drive In and Goregirl’s Dungeon. The Blogathon still has one day left, so be sure to take a look.

Until next time…

“There was no skill to their taking — only overpowering force. He had that feeling again that he had had before: that life was neither good nor pleasant nor worth the living. You started out in blood and stench with the echoes of your mother’s dying screams inside of you somewhere so that unrecognized, unremembered, they were there a part of you; then afterwards you were the hunted, always the hunted, running with that tiredness inside of you that was part of death itself, the knowing always in the end that the running was no good because you’d be pulled down — by the big ones, the strong ones, the ones whose world would crash about their heads if they permitted you, the small the wily, the different, to go on living. Or they worried you to death in small and ugly ways: by telling you what seat you might take at a table, by the epithets with which they addressed you, by forbidding you to wear fur or bear a sword or take to wife a girl of different station. Small ways and ugly, but they killed something inside of you — your pride of manhood perhaps your belief in yourself until you became the beast-thing that they were and lit candles and rang bells and ran weeping and howling to prostrate yourself before the unknown and unknowable because you had to have something to cling to against the onrushing dark even if it were only the gibbering ghosts of other men’s fears labelled god or saint or holy spirit….” — Frank Yerby, “The Saracen Blade”

Sure, that passage is a wall of text, but it’s a POWERFUL wall of text.

EDIT (03/22/15) – Removed broken link to swordfight video clip. Looks like all clips from this film have vanished from the interwebs. I’ll keep on the lookout, though. I’d love to have a trailer, if such a thing exists. Got a tip? Please leave a comment. Much appreciated!

Savage! Sinful! Spectacular!

These three words are used to describe William Castle’s peplum epic, Slaves of Babylon (1953), in the poster below. Promising to tell the tale of “The last days and nights of mighty Babylon”, the film is part of Castle’s journeyman era, just a few years before he adopted the Barnumesque promotional gusto that would cement his legacy. Slaves enters the “peplum”, or “sword-and-sandal”, era early, before Kirk Douglas as Ulysses (1954), Charlton Heston as Ben-Hur (1959), or the countless Hercules and Samson films that would define the genre in the decades to come. The most obvious influence on Slaves is the MGM Technicolor epic Quo Vadis (1951), which became the highest grossing film of the year and earned eight Academy Award nominations.

Today, as part of The William Castle Blogathon, hosted by The Last Drive In and Goregirl’s Dungeon, we’re going to take a closer look at Slaves of Babylon. Directed by William Castle from a story and screenplay written by DeVallon Scott, Slaves was the second of four collaborations between the two (along with Conquest of Cochise (1953), The Iron Glove (1954), and The Saracen Blade (1954)). It is largely an adaptation of the biblical Book of Daniel, though Daniel (played by the Yiddish Laurence Olivier, Maurice Schwartz) appears only sporadically. The bulk of the narrative is driven by the minor prophet Nahum (Richard Conte), depicted here as a student and contemporary of Daniel.

Richard Conte as Nahum

Richard Conte was discovered by John Garfield and Elia Kazan while working as a singing waiter at a Connecticut resort. While many Hollywood actors were off fighting the good fight in WWII, Conte signed a long-term contract with 20th Century Fox, groomed to be the “New John Garfield”. He began his career playing mostly soldiers, but by the late 1940s, he had transitioned to film noir. Conte’s Jersey accent occasionally creeps through here as the kingmaker Nahum.

Linda Christian as Princess Panthea

Born Blanca Rosa Welter, Linda Christian was given her screen name by then lover Errol Flynn after Bounty mutineer Fletcher Christian. Flynn convinced her to give up her medical studies and move to Hollywood. She was quickly spotted by MGM head honcho Louis B. Mayer and offered a seven-year contract, nicknamed “The Anatomic Bomb” by the studio. Her best known work before Babylon was Tarzan and the Mermaids (1948), Johnny Weissmuller’s last Tarzan film.

Shortly thereafter, she became more famous for marrying actor Tyrone Power than any of her film roles. While they never ended up working together, Christian and Power were offered the leading roles in From Here to Eternity (1953), but Power turned the project down. Eternity would go on to win eight Oscars. Neither Christian nor Power would ever take home that prize.

Linda Christian’s Princess Panthea is a bit of a biblical femme fatale, putting her own interests first and foremost and mercurial in her moods and affections. She is a natural seductress and manipulator, a character very much at home in the sword and sorcery fiction of H. Rider Haggard or Robert E. Howard. Unlike most of her ilk (spoiler alert!), she does not suffer from her opportunistic nature, emerging entirely unscathed.

Perhaps because she is a true polyglot, able to speak six languages fluently, Linda Christian’s accent fluctuates wildly as Panthea. Most often, it comes across as Shakespearean, with a languid, breathy delivery. At other times, though, she sounds vaguely Eastern European, like a Russian tsaritsa. Your mileage may vary.

Terry Kilburn as Cyrus the Great

Terry Kilburn achieved film fame at a very young age, appearing as Tiny Tim in the MGM production of A Christmas Carol (1938) and four generations of students to the title teacher in Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939). Throughout the 1940s and into the early 1950s, Kilburn would appear in a wide variety of adventure films, from Swiss Family Robinson (1940) through Only the Valiant (1951) and often as a sailor in swashbucklers such as Song of Scheherazade (1947), Tyrant of the Sea (1950), and Fortunes of Captain Blood (1950). He also played the cub reporter Seymour in four Bulldog Drummond mysteries from 1947-1948.

While 26 at the time of the film’s release, Kilburn appears much younger. This helps him portray Cyrus as an uncertain ruler, prone to youthful indiscretions and easily steered by the savvy Nahum. This contrasts rather harshly with most historical accounts that place Cyrus as one of the great military leaders of the ancient world, but Nahum’s the star here, the power behind the throne just as Daniel was to King Nebuchadnezzar.

Leslie Bradley as King Nebuchadnezzar

Leslie Bradley had uncredited roles in Prince of Foxes (1949), which would provide footage for Castle’s The Saracen Blade (1954), and the highly successful biblical epic Quo Vadis (1951).

Michael Ansara as Prince Belshazzar

Syrian-born Michael Ansara appeared in the western adventure Only the Valiant (1951) with Terry Kilburn and in the Castle peplum Serpent of the Nile (1953) along with Michael Fox, Robert Griffin, and Julie Newmar. Ansara followed Slaves with dramatically more successful biblical epics, taking uncredited roles in the Oscar-winning films The Robe (1953, as Judas) and The Ten Commandments (1959). How do you not credit Judas?

Ansara, in a mere supporting role, practically steals this film away from its stars. His Belshazzar is delightfully wicked, and his line delivery reminded me of an angry William T. Riker (Jonathan Frakes). Ansara would be no stranger to science fiction television, playing Klingon commander Kang in three separate Star Trek series as well as Kane on Buck Rogers in the 25th Century.

Slaves of Babylon (1953)

We open with a reading from the “Book of Daniel”, narrated by Michael Fox, who previously appeared in the William Castle pelpum Serpent of the Nile (1953) and who would go on to narrate another William Castle/DeVallon Scott collaboration, The Iron Glove (1954). For the historically and/or geographically challenged, Babylon was located some 53 miles south of Baghdad and was responsible for the destruction of Jerusalem. The titular Hebrew slaves were taken back to Babylon to build the fabled Hanging Gardens (represented here by some gorgeous matte paintings) and the Temple of Bel-Marduk, but they refused to worship at the latter, even under penalty of death.

Daniel, however, has found favor with King Nebuchadnezzar, who relies upon his sage counsel. Prince Belshazzar takes strong exception to his father’s tolerance, claiming “He has bewitched you!” and “It is Daniel who really rules Babylon!”

“I rule Babylon!”

“But Daniel sits at your right hand. Why do I not sit at your right hand?”

“Soon you will sit on the throne itself, my son.”

Daniel seeks an audience, and while Belshazzar is insulted, his father welcomes the interruption to end their ongoing quarrel.

At the house of Rachel (Ruth Storey), Daniel’s rebellious student Nahum finds refuge and a tender kiss while soldiers search for him outside. She urges him to flee Babylon with her, but he refuses to leave Daniel. Daniel himself then enters to tell Nahum he must go to the ruins of Jerusalem, which Nahum has never seen. Afterwards, Nahum must seek a shepherd boy named Cyrus who has the power to overthrow Babylon, but if he never uses this power, Cyrus will die a shepherd. Knowing his pupil’s limitations, Daniel urges Nahum to be wise and controlled, as he is. Nahum eagerly takes up this noble quest, leaving Rachel to lament her loss.

Exiting Babylon undetected is no easy feat, however. Nahum recalls a way out from his childhood. Some unexpected underwater photography highlights Nahum’s escape, squeezing between bars blocking a conduit to the River Euphrates and the shore outside the city.

In the Kingdom of Media, Nahum makes inquiries about the shepherd boy Cyrus. Stopping to drink at a river bank, he hears a shepherd’s flute and wanders over to ask his tired question. He is surprised (but we shouldn’t be) to find that he speaks to Cyrus himself.

Cyrus doesn’t like strangers, dismissing Nahum out of hand. Nahum won’t be so easily turned away, however, and resorts to force to subdue Cyrus. At the shepherd’s home, Cyrus’s father (Wheaton Chambers) offers hospitality to the visitor from Babylon. Undaunted by propriety, Nahum calls Cyrus’ parentage into question and asks his mother (Beatrice Maude) to speak the truth, but is horrified to find she has no tongue.

Cyrus’ father knows not how she lost it, and she cannot tell him, but it happened while she was heavy with child and Cyrus’ father was off in the mountains. She served in the palace at the time and perhaps insulted someone important. While the menfolk speculate, she produces a woven cloth that tells the story of Cyrus.

Nahum examines it and tells the tale. “The visit from the king’s men, the child swathed in royal purple, given to you to expose in the wilderness to die because they were afraid to kill a king’s son. Your own child, stillborn. The dead child put out on the hillside, the living child raised as your own, and you could never tell him because of what the soldiers had done to you.” This story, as written by Herodotus, is but one of many legends of abandoned children of noble birth returning to claim their royal birthright, putting Cyrus alongside such luminaries as Oedipus the Greek and Romulus and Remus, founders of Rome.

Cyrus wishes to die a shepherd and wants nothing to do with the kingdom of his grandfather, King Astyages, but when Nahum indicates that he would be free to marry whoever he chooses, Cyrus suddenly shows interest.

Nahum has the tapestry brought to Cyrus’ mother, Mandane (Ernestine Barrier), as a gift. When she tracks Nahum down, he shows her the Talisman of Mithra that was found around the infant Cyrus’ neck. King Astyages orders Cyrus killed, but his daughter stays the execution and spares the boy she now knows to be her only son.

Cyrus is quickly accepted as a prince in the court of Astyages, and Nahum is tasked with teaching the new ruler of Persia the ways of kingship. Before leaving for his new lands, Cyrus wishes to wed the Princess Panthea, but he is skittish about speaking to her and betraying his humble origins. He asks Nahum to play John Alden to his Miles Standish and speak on his behalf instead.

When we are first introduced to Princess Panthea, she is lounging about her luxurious chambers petting her leopard. Sometimes a leopard is just a leopard, I suppose, but the way Linda Christian vamps it up here is captivating. She has only the scantest interest in Cyrus, his title, and his messenger Nahum.

To gild the proverbial lily, Julie Newmar has a brief cameo as our forbidden dancer du jour. Nahum tries to goad the distracted Cyrus into making war on Astyages, even suggesting that Princess Panthea may wed someone else if he waits too long. Suddenly, Nahum catches the dancer by the wrist before she can plunge a blade into the heart of Cyrus. She immediately fingers King Astyages as her employer, convincing Cyrus to give the attack order against his own grandfather.

Best known as Catwoman in television’s Batman starring Adam West, Newmar was still going by her birth name of Newmeyer when she played the would-be assassin. Earlier that same year, she had been a feature dancer clad in gold paint for the William Castle peplum Serpent of the Nile (1953) and later in the widely panned sequel to The Robe, Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954).

The campaign goes poorly for Cyrus, and in the very first battle, he is saved from certain death by Nahum. He swears to reward Nahum with whatever he desires, but Nahum insists he will only redeem his wish once Babylon is taken. Cyrus can’t see that happening any time soon, since he’s lost three battles in a row to his grandfather.

In Babylon, King Nebuchadnezzar has been pressured into making a decree that anyone who prays to a deity other than Bel-Marduk for the next thirty days will be thrown into a den of lions. Daniel, predictably, defies this order and is arrested. He is taken into custody peacefully, even when stoned in the streets by angry mobs.

King Nebuchadnezzar begs Daniel to pray to Bel-Marduk. When Daniel refuses, Nebuchadnezzar tells him that he has doomed himself. “Release the lions. We will return at daybreak.”

When Nebuchadnezzar returns, the lions are lying around Daniel, docile. The guard thinks it a trick, so Nebuchadnezzar shoves him into the cell to be devoured. During his time with the lions, Daniel has had an epiphany and now knows how to help Cyrus.

Back in Media, Nahum tells an envoy from King Astyages that tomorrow, at the ninth hour after sunrise, the entire world will grow dark unless Astyages’ men throw down their arms. During the battle, a solar eclipse vindicates the prophecy, presumably delivered to Nahum by Daniel but historically attributed to Thales (an opponent of Cyrus) and the King of Lydia. The soldiers of Astyages drop their weapons in fear, and Astyages surrenders his throne to his grandson. Cyrus spares his grandfather’s life but reduces him to a lowly shepherd.

Nahum tries to keep Cyrus hungry, but the young king is done with conquest and just wants his Panthea. Princess Panthea receives Nahum, but says she’s not interested in him, the throne of Persia, or Media. When Nahum offers the throne of Babylon, that finally piques her interest. Rather than offer up the hand of Cyrus as was requested, Nahum claims that Daniel will spread word in Babylon of Panthea’s beauty, intriguing Prince Belshazzar into arranging their marriage.

Meanwhile, Belshazzar is busy burning Hebrews, but they walk out of the flames unscathed. This is a dramatization of the tale of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, though the men are unnamed here and it is the cruel Belshazzar not Nebuchadnezzar who orders the execution. Neither are the guards burned who cast them in. It is perhaps the weakest of the miracles depicted in the film and should really have been given more oomph than some cheap rear projection.

Cyrus is angry that Nahum has not disbanded the army as commanded. Before it can be done, Nahum reveals that Panthea is en route to Babylon to be betrothed to Belshazzar. As Nahum cheekily gets ready to disband the army, Cyrus stops him, now wanting to march on Babylon.

Cyrus’ forces intercept the caravan of Panthea, and she consents to be his queen, but only if he succeeds in taking the throne of Babylon, a kingdom worthy of her stature. Cyrus entrusts Nahum to escort Panthea safely behind his army, but warns that if she complains about his stewardship, it will mean his death. Sounds like nothing could go wrong there, right?

Nahum confronts her in her pavilion, angry that she did not wait in Tarsus as instructed, but she has clearly seen through his scheme and is working her own angle now. “Cyrus or Belshazzar… I must win with either. You must lose with both.”

Over the five-day journey to Babylon, she tries to seduce him and is surprised to find that this well-spoken statesman used to be a slave. He tells her stories of his people, such as that of Ruth and of Joseph, Son of Jacob. This seems to satisfy her need for attention and affection… for now.

As King Nebuchadnezzar grows senile and enfeebled, Belshazzar believes that his father has been bewitched by Daniel. Nebuchadnezzar seeks forgiveness from Daniel, who passes this request along to God, and the stricken king receives clarity of thought briefly before expiring. Belshazzar walks in to find his father dead at Daniel’s feet. Before he can act, word arrives that Cyrus has reached the city walls with his vast army.

Belshazzar shouts from the walls, telling the Medians that they will starve during a siege while his people eat heartily from their stockpiles of food. “Babylon will live forever under the protection of the all-powerful god, Bel-Marduk!”

Elsewhere, Panthea dances seductively for Nahum, eventually coming to rest her chin suggestively on his thigh. After he tells her the tale of Joseph, they kiss. “In all my life, they taught me only one thing, that I should one day be a queen, but I want to be a woman… with you.” Nahum spurns her advances just as Cyrus walks in, seeking his counsel. Without explaining her ire to Cyrus, she angrily vows to decide Nahum’s fate after Babylon has been taken.

Inside the city, Belshazzar is warned about the danger of the slaves, who might open the gates to the invaders, and is encouraged to put them all to the sword. Rather than spark open revolt in the streets, Belshazzar tells the Hebrews that they are free to return to Jerusalem by the east gate that night.

Daniel interrupts Belshazzar’s revelry to ask for the return of the sacred vessels from the temple at Jerusalem. Belshazzar and his advisers mock this humble request. The sacred vessels are brought to Belshazzar, who, along with his general, drinks wine from them. Inexplicably, a spectral hand writes out Hebrew script (right to left, as is proper), the oft-cited “writing on the wall”, shocking all in attendance. Daniel translates it into a long prophecy of doom for Belshazzar.

Clearly rattled, Belshazzar responds with vicious bravado. “It is not I that am doomed, but your people, all of you. Even now they are being destroyed.”

This is no idle threat, as the departing Hebrews have been trapped in a high-walled ravine where the surrounding brush is set alight by the Babylonians, leaving the Hebrews to burn to death. A sudden, miraculous rain spares them, but Belshazzar does not know that, and he proclaims Daniel’s god false.

Outside, Nahum suggests that Cyrus’ men use cover of night and fog to re-enter the city through his escape path, the river gate. Before Belshazzar can slay Daniel, a thrown spear buries itself in his back, cast by brave Nahum. The forces of Babylon, sodden with wine, spiritually shattered, leaderless, and taken unawares are summarily defeated.

Victorious, Panthea broods on the throne of Babylon alongside King Cyrus. Cyrus announces that he is ready to redeem his two vows, one to Nahum, the other to Panthea. Nahum regifts his favor to his mentor Daniel. Daniel asks for freedom to return to Jerusalem with his people.

Panthea decides Nahum’s fate. “Yes, he shall die… but in his own land, surrounded by his brothers. For your god will surely visit you and bring you out of the land of exile back to the land of your fathers, and from this day on you shall never again look on Babylon.”

Leaving Babylon forevermore, Nahum is reunited with Rachel, his one true love, and they wend their way toward a distant rainbow. And Jerusalem knew happiness and peace for the rest of days. Well, not really, obviously, but that’s “THE END” for now.

Click on the banner above for more of “The William Castle Blogathon” hosted by The Last Drive In & Goregirl’s Dungeon (July 29 – Aug. 2, 2013)

Savage? Sinful? Spectacular? Sadly, no.

Tame. Tepid. Tolerable. All would be better descriptors. William Castle’s direction is competent but lifeless. The various miracles depicted in the film are given little to no weight, the score doesn’t swell, and the actors mostly respond as if it’s just another day at the office, especially the Hebrews walking out of the furnace and, presumably, directly toward craft services.

Still, it’s not a terrible film by any stretch, and as far as adaptations of the Book of Daniel go, I’m sure you can find far worse. Certainly, it’s not enough to scare me away from tackling another William Castle/DeVallon Scott collaboration in two days’ time, their last, The Saracen Blade (1954). Hopefully you won’t be scared off as well and will return to check out Ricardo Montalbán buckling his swash.

Be sure to click the banner above for more of The William Castle Blogathon, hosted by The Last Drive In and Goregirl’s Dungeon. Castle was a prolific director, and with five days of coverage and dozens of participating blogs, there’s sure to be something for everyone. Until next time…

“I created the peplum so you can eat in it.

You can have a dessert, you can have another sandwich.”

– Fashion designer Alber Elbaz in 2012

Pretty sure the ancient Greeks invented the peplum. Just sayin’.

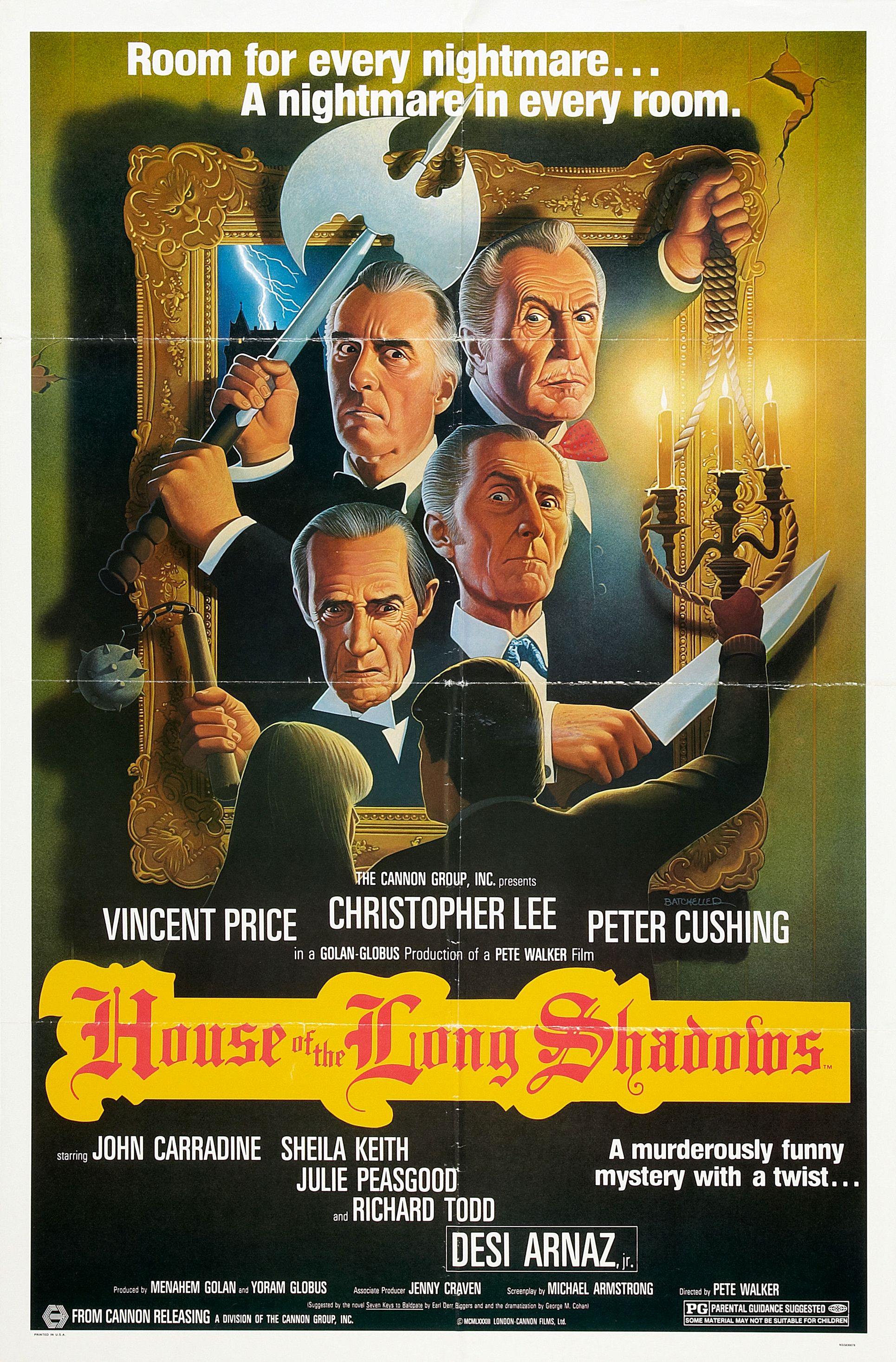

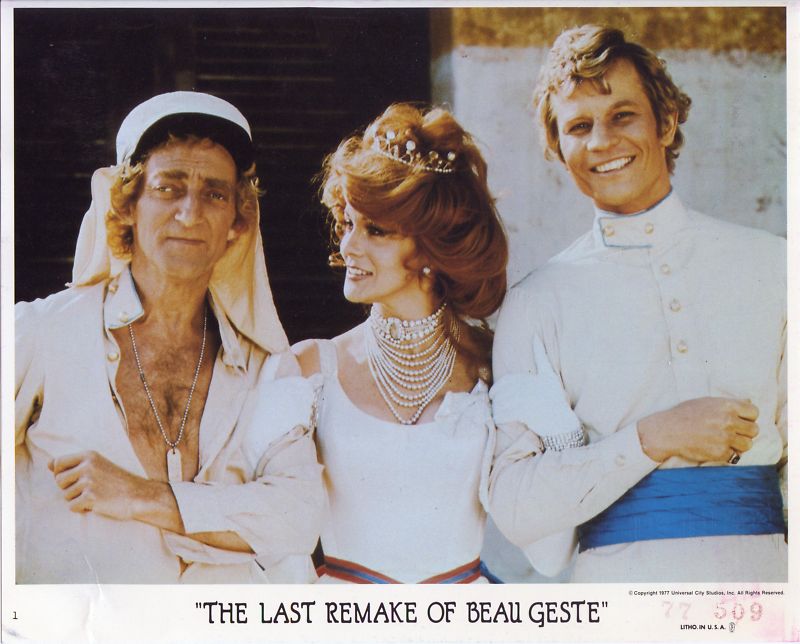

Remembering Marty Feldman

Last year’s tribute to Marty Feldman, covering three of my favorite performances, proved to be our most popular post to date here at WeirdFlix. This year, I thought we’d break new ground and examine a Feldman film I hadn’t yet seen. The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977) was written and directed by Feldman with perennial musketeer Michael York in the title role and Feldman as his “identical” twin brother, Digby Geste.

The title references the many adaptations of P. C. Wren’s adventure novel Beau Geste, first published in 1924. There are three earnest adaptations and one BBC serial, each with its own variation on Beau’s exploits in the French Foreign Legion. Last Remake joins such comedy luminaries as Laurel and Hardy’s Beau Hunks (1931) and the Carry On film Follow that Camel (1967) in spoofing the tale of derring-do.

The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977)

Marty Feldman made his feature film directorial debut with The Last Remake of Beau Geste, after directing an episode of the Mel Brooks Robin Hood parody When Things Were Rotten (1975) for the ABC Network. By the late 1970s, Marty was already a veteran of Mel Brooks/Gene Wilder farces, having appeared in Young Frankenstein (1974), The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother (1975), and Silent Movie (1976). All three were very successful, especially given their modest budgets.

As The Last Remake opens, it becomes apparent that Marty Feldman was a great influence on his former collaborators Graham Chapman and John Cleese of Monty Python fame. Feldman indulges in not only parodying the adventure genre, but in deconstructing the tropes of film itself. Quite literally, in the case of the opening credits. This is perhaps zanier than even Mel Brooks’ fans are accustomed to, if one is not familiar with the Python style.

“The place: North Africa. The year: 1906.”

A rather amusing opening song explains the mercenary nature of the French Foreign Legion to the uninitiated. But first, we must backtrack some years to Merry Olde England and stately Geste Manor. Sir Hector Geste (Trevor Howard) eagerly awaits the birth of his son Beau, having already named him and proclaimed him an epic hero. When the child born proves to be a daughter, the enraged Sir Hector is forced to seek out the offerings at Wormwood & Gall Boys Orphanage.

Sir Hector has very specific requirements. “He’s got to be tall, blonde, and, per my specifications, he must have an aristocratic bearing and the necessary blue eyes. A lad to whom I can confidently bequeath my own noble features. I shall eventually need him to reach a height of six-feet-one and, naturally, he will be brought up with an English gentleman’s attitude and love of slaughter. That seems to cover the essentials.” He soon spies a curly, towheaded boy laying into the other ruffians with not a speck of dirt upon him. Young Obadiah Spittle is immediately rechristened Beau Geste.

Miss Wormwood protests, however. For a mere twelve guineas, she’ll throw in his identical twin brother, Digby. Sir Hector, envisioning two epic heroes, agrees sight unseen. Where they got a child version of Marty Feldman, I’ll never know, but it works.

The idyllic childhood of Beau, Digby, and Isabel Geste is disrupted when Sir Hector is called off to war. Before he can leave on his grand escapade, he shows Beau the Geste family treasure, the legendary Blue Water Sapphire, a gem of such beauty, the Hope Diamond and the Koh-i-Noor pale in comparison. Sir Hector puts it in rather cruder terms, but I’ll take the high road here.

While Sir Hector is off to war, the Geste children grow to young adulthood. Digby is now played by Marty Feldman while Michael York takes the title role of Beau. York was no stranger to swashbuckling, having previously appeared in Director Franco Zeffirelli’s Shakespeare adaptations, The Taming of the Shrew (1967) and Romeo and Juliet (1968). In the latter, he played the flamboyant swordsman Tybalt. It isn’t much of a stretch from the “Prince of Cats” to the role York is most often associated with, that of D’Artagnan in The Three Musketeers (1973) and The Four Musketeers (1974).

“And what of the lovely Isabel? She practiced and practiced and became an accomplished… virgin.” Primarily a television actress, Sinéad Cusack takes on the role of the adult Isabel. She had debuted with an uncredited role in Rocket to the Moon (1967) with Terry-Thomas (Geste‘s Governor), then appeared with Michael York in the costume drama Alfred the Great (1969). She performed alongside her father, respected Irish actor and “The Man Who Would Be Who”, Cyril Cusack, in Roddy McDowell’s The Ballad of Tam Lin (1970) for AIP.

Sir Hector returns from the Sudan with a chest full of medals and a trophy wife, Flavia (played by the voluptuous Ann-Margret). It may seem hard to believe in retrospect, but Ann-Margret had been nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for Carnal Knowledge (1971), then nominated for a Best Actress Oscar for Tommy (1975). She was perhaps born to play “Lady Booby” in Tony Richardson’s adaptation of the costume comedy Joseph Andrews (1977), and, though Geste was released just a few months later, it feels like she just reprises the role of the lusty widow.

Indeed, Flavia proves “too much for a man of his age,” and Sir Hector suffers a heart attack while in the throes of passion with his new bride. “He overcame himself.” Flavia gets an early start on grieving and arranges a nunnery for both Isabel and Digby, while she has other plans for handsome young Beau.

When she openly plans to sell the Blue Water to gentlemen from Cartier’s, the lights go out and the sapphire disappears. This plays out in an extended sequence that overstays its welcome but finishes strong for fans of Ann-Margret. A subsequent letter from Beau reveals that he has left for North Africa with the family treasure to keep it out of the hands of his wicked stepmother.

Digby keeps Beau’s secret and takes the rap for the theft. He is sentenced to hard labor, “956 years or life… whichever is the longer.”

When we catch up to Beau, he is “somewhere in Morocco…”

The new recruits to the French Foreign Legion are ready for inspection by Sergeant Markov (a bombastic Peter Ustinov). The veteran actor previously teamed with Michael York in Logan’s Run (1976) and played a charlatan in the Disney adventure Treasure of Matecumbe (1976), the first feature-length movie filmed on Disney’s Florida property. He will teach his little “fledermauses” how to die with dignity in the French fashion.

Meanwhile, Flavia visits Digby in prison and tries to get him to tell her where Beau has taken the Blue Water Sapphire. Digby rather vocally refuses to speak, forcing Flavia into the bed of the Governor (Terry-Thomas). There, she convinces him to arrange Digby’s “escape”, figuring he will lead her right to Beau. “It’s been a business doing pleasure with you,” she says with a wicked smile.

Here, the film takes a cinematic detour, paying homage to the 1926 silent film adaptation of Beau Geste, starring Ronald Colman. Soon, despite his inept efforts, Digby is free and reunited with his twin in Morocco. While they think they’ve seen the last of mother, Flavia is in hot pursuit and making good time with the delightfully foppish General Pecheur (Henry Gibson).

Gibson was already a veteran TV actor before Geste. He voiced the beloved pig Wilbur in Charlotte’s Web (1973). He also appeared in Director Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye (1973) and Nashville (1975), getting a Golden Globe nomination for Best Supporting Actor in the latter.

Pecheur introduces Flavia to Sergeant Markov. For 200 francs, Flavia hires Markov to retrieve the gem from Beau, using whatever means necessary, and deliver it to her at their next destination, Fort Zindeneuf. Markov’s assistant, Boldini (Roy Kinnear) lays the groundwork for betrayal by revealing that the paste gem she seeks is no mere trinket, but the fabled Blue Water Sapphire.

En route to Fort Zindeneuf, the Legionnaires are assaulted by Arabs, and the Geste Boys get an opportunity to test their mettle. Inexplicably, a brown-faced Ed McMahon shows up to give us the score and take us out to a commercial break. Avery Schreiber does double duty as an Arab raider and as Honest Hakkim, a used camel salesman. When we return to the action, the Brothers Geste save the regiment banner and the dignity of the Legion.

When the march resumes, Digby finds himself separated from the unit and wandering into a “Mirage Area”. Here, we have another cinematic detour as Marty “Gumps” himself into footage from the 1939 Paramount adaptation of Beau Geste with Gary Cooper. If this scene is to be believed, Cooper’s trademark lackadaisical speech pattern is the result of “Moroccan Gold” cigarettes. Sounds canonical to me.

While Digby negotiates exit from the earlier film and the “Mirage Area”, we catch up with the Sheikh, leader of the Arabs. He enters a tent, and suprise # 1 is that he’s there to meet General Pecheur and Flavia Geste. Surprise # 2 is that when he unwraps his keffiyeh, we see he is none other than James Earl Jones. Surprise # 3 is that he’s a very proper British gentleman, not at all the desert savage we would expect.

Star Wars (1977) was released just two months prior to Geste, but Jones would not be widely associated with the Darth Vader role for some time, primarily because his voiceover work was uncredited at his own request. He starred in Swashbuckler (1976) with comedian Avery Schreiber, who plays his Sheikh’s Aide here.

The subsequent scene reveals a sadly underdeveloped plot twist, the fact that Pecheur is actually financing both sides of the conflict and expects better results from his Arab ally. He demands an attack on Fort Zindeneuf in which everyone is killed.

At Fort Zindeneuf, a regimental ball is held to celebrate the Legion’s victory. Attempts by Boldini to locate the Blue Water Sapphire, vulgar though they may be, prove fruitless. Empty-handed, Markov deftly avoids Flavia, leaving her to dance with her stepson Beau.

General Pecheur exits the ball early, aware that the Arabs are soon to beseige the fort. As they ride by, we find Flavia and Beau in the midst of a moonlit rendezvous. She lets slip some pillow talk that she doesn’t want to go back to the fort since it will be attacked at dawn. This restirs Beau’s passions, and they arrive on horseback in the midst of the Arab charge.

Beau reveals that the Legionnaires have been supplied with blank ammunition. The men voice their support for Beau Geste and offer to “die to the last man” behind him, but the supposed epic hero is aghast. “No, you can be free! So, for your own sakes, desert! Get out of here! Go and be rotten to people, but do it for a decent living wage!”

Digby and the Sheikh seem to be the only ones horrified by this turn of events. “How can I lead you if you won’t wait for me?!” The Sheikh rides off into the sunset with Rudolph Valentino (Martin Snaric), off to Hollywood and silent film. This leaves Markov and Beau to duel over the Blue Water and a pugilistically adept Flavia to save Digby from Boldini.

Beau honors what seems to be Markov’s last request, to reveal the hidden location of the Blue Water. He takes a saber to Markov’s wooden leg and the sapphire tumbles free from the hollow inner compartment. Markov and Boldini flee with “the Geste family fortune”, but Beau confesses it’s a fake. The real Blue Water has been in a safety deposit box in Paris the whole time.

As the last man alive in Fort Zindeneuf, Digby is hailed as a hero and reunites with Isabel at Geste Manor while Beau and Flavia retire to a posh beach resort.

FIN.

Marty Feldman, Ann-Margret, and Michael York in a

promotional photo for The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977)

As is common with these sorts of spoofs, The Last Remake of Beau Geste is wildly uneven, but still quite amusing. Re-cut by Universal while Marty was touring Europe to promote the film, his version never made it to theaters. Though performing well in test screenings, Universal sticked to their guns and, sadly, it remains unavailable.

In Blazing Saddles (1974) and Young Frankenstein (1974), Mel Brooks managed to make decent, if light-hearted, examples of the genres he parodied, filled with endearing characters. Broader spoofs such as Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) and Airplane! (1980) filled the running time with non sequitur gags to account for their large ensemble casts of largely undeveloped characters. Sadly, the extant cut of Geste fails to achieve either effect, but it still contains enough laughs to be worth watching on a lazy Sunday afternoon.

Though it may not be the film he intended to release, it was great to spend time with the late, great Marty Feldman once again. We’ll be sure to do it again some time.

Now, I just have to find the supposedly serious 1966 adaptation of Beau Geste starring Doug McClure, Leslie Nielsen, and Telly Savalas. That’s sure to be a hoot.

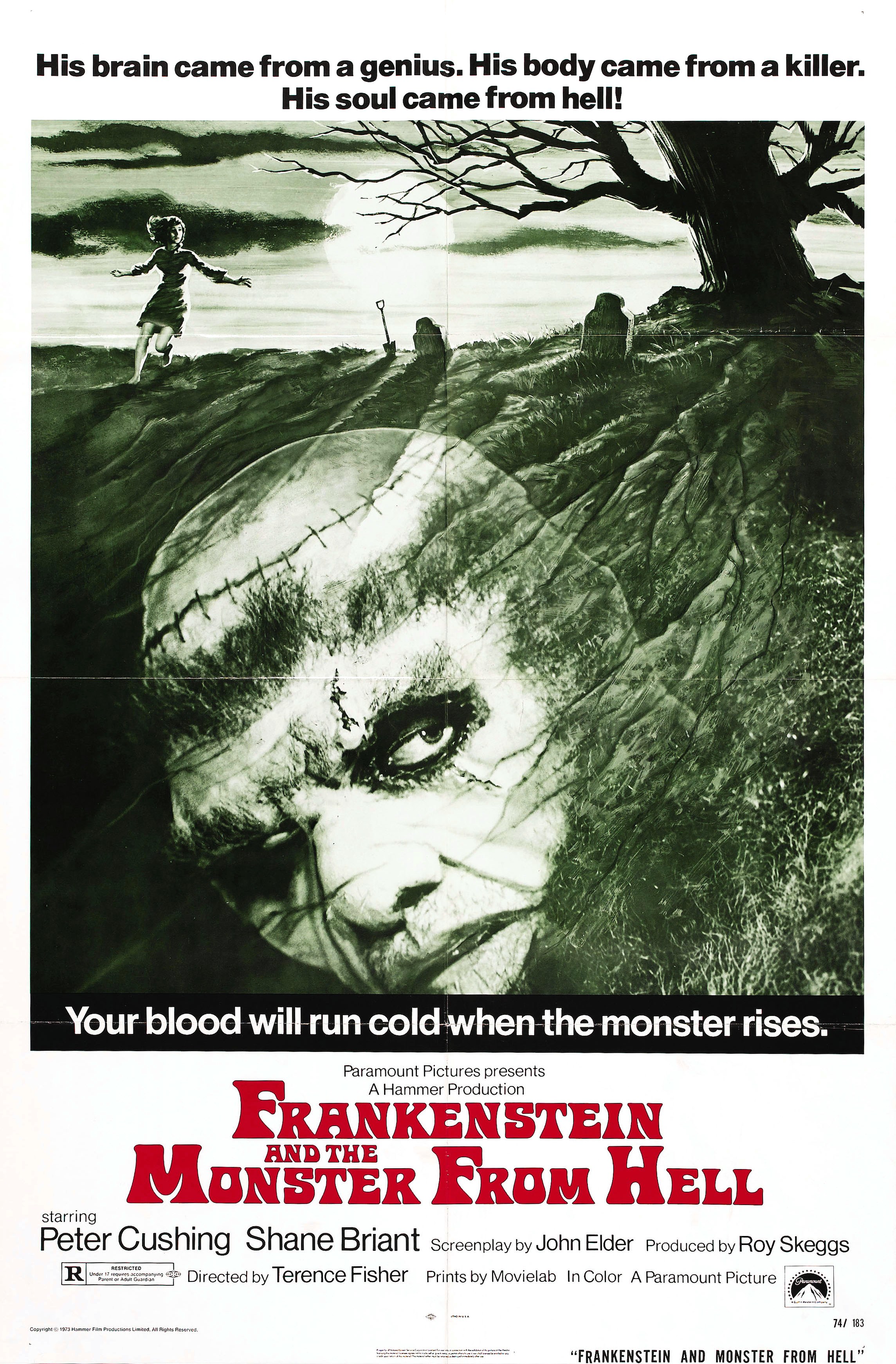

All Good Things

“All good things must come to an end.” — Chaucer

Welcome back to Day Seven of the

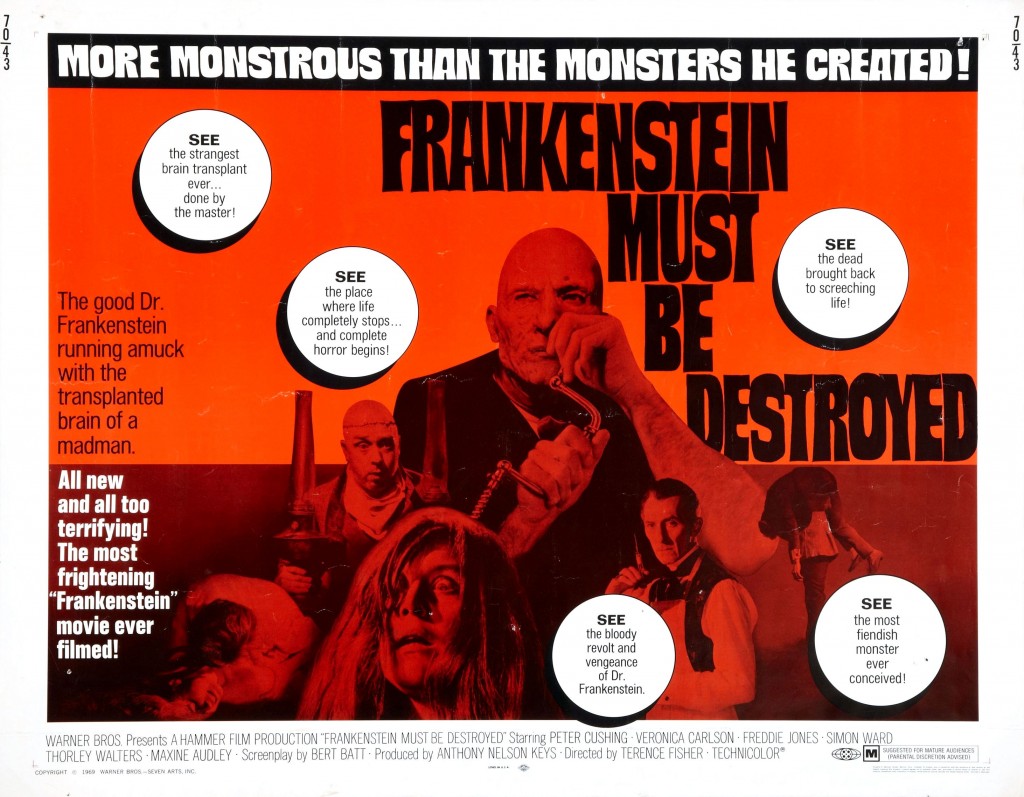

Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon. This is it, the final chapter in the Hammer Frankenstein saga. After Jimmy Sangster’s attempt at a younger, more comedic Frankenstein in The Horror of Frankenstein (1970), we’re back on track with Cushing in the title role and Terence Fisher in the director’s chair (sadly, for the last time). The script, by Anthony Hinds writing as John Elder, brings back familiar gimmicks and themes from the series to bring things to a satisfying conclusion. I must confess that I do not know how obvious the end was for Hammer and company and whether or not they intended to continue the series past Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974).

Despite being passed over for Horror, Peter Cushing kept quite busy in the intervening years. After an unbilled cameo as Baron Frankenstein in the Rat Pack farce One More Time (1970), he continued to be a linchpin for Hammer. He appeared in two installments of The Karnstein Trilogy, The Vampire Lovers (1970) and Twins of Evil (1971). He also continued his work in the Amicus portmanteau films with The House That Dripped Blood (1971) (with Christopher Lee, though in different segments), his iconic portrayal of the tragic Arthur Edward Grimsdyke in Tales from the Crypt (1972), as well as Asylum (1972). Lee and Cushing also took their chemistry outside of Hammer with the criminally underrated Horror Express (1972), Nothing But the Night (1973), and The Creeping Flesh (1973). In all, it was a golden age for Mr. Cushing’s fans when his final performance as Frankenstein finally made its way to theaters.

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974)

We begin with a body-snatching, not exactly breaking new ground if you’ll pardon the pun, but the recipient is not Baron Victor Frankenstein as one might assume. No, we are introduced instead to Dr. Simon Helder (Shane Briant), a detached scientist pursuing those familiar forbidden avenues of research first trod by the Baron. He is found out by the authorities and committed to an asylum, much to the shock of Asylum Director Adolf Klauss (John Stratton), who at first assumes Helder must be the new staff doctor.

As the fresh fish on the block, Helder gets some rough treatment, not the least of which is a nasty hose-down as if he were some filthy indigent rather than a learned doctor. When the abuse is interrupted, we zoom in on Helder’s savior and find it to be none other than Baron Victor Frankenstein. In subsequent discussion with Director Klauss, we learn that Victor has taken on a new identity once again as Dr. Carl Victor and that Klauss is a willing accomplice in the charade.

Hammer Films and Director Terence Fisher always gave Cushing great freedom with subtle character notes, including his handling of props. Here, he was given a hand in the design of his wig, but the results show Peter to be a more accomplished actor than wefter and he would later describe the result as making him look like Helen Hayes. Victor also sports his black leather gloves again, his hands burned at the end of either The Evil of Frankenstein or Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, take your pick.

Helder is quite the student of Frankenstein’s work, however, and recognizes him immediately. He convinces Victor to take him under his wing in exchange for assistance in his latest experiments. Helder gets the guided tour and meets some of the other inmates including a man who believes he is God. Victor makes the perhaps self-deprecating joke that the patient is not the first to suffer under that delusion. It should be patently obvious that all of these, from sculptor to mathematician, are mere raw materials for Victor, his living Erector Set. To drive the point home, when the dead sculptor’s coffin is accidentally dropped and falls open, we see he has lost his talented hands post-mortem.

Madeline Smith, Shane Briant, David Prowse, and Peter Cushing in

Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974)

The surgery scenes are the most graphic and unflinching depictions of Victor’s work in the series. Briant, having previously appeared in Hammer’s Demons of the Mind (1972), doesn’t even try to hold his own against Cushing, and it perhaps works to the film’s advantage. His Helder proves a valuable assistant, able to perform the delicate operations now denied to Frankenstein due to his damaged hands. Frankenstein is giddy as his project begins to take shape, cackling like a madman in juxtaposition to Helder’s cold callousness, and one could envision them as father and son working on a ’57 Chevy instead of building a man. There’s even a nice little nod to Curse as Victor sits down for some chow before the big brain swap.