Welcome to Day Six of the

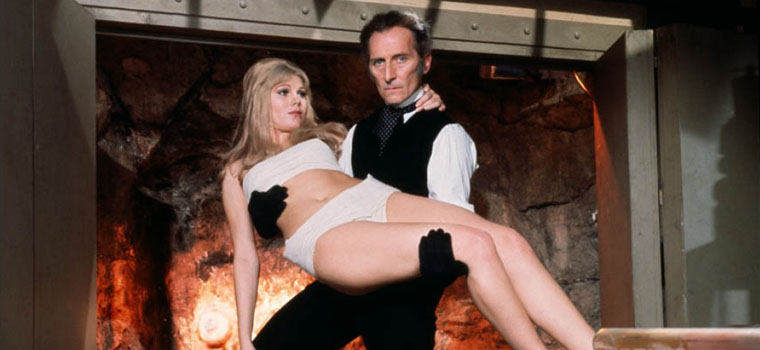

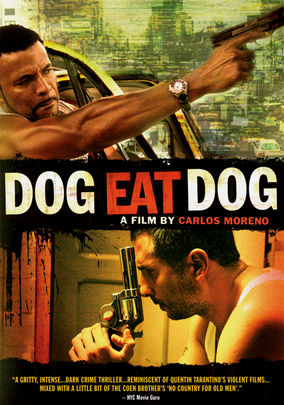

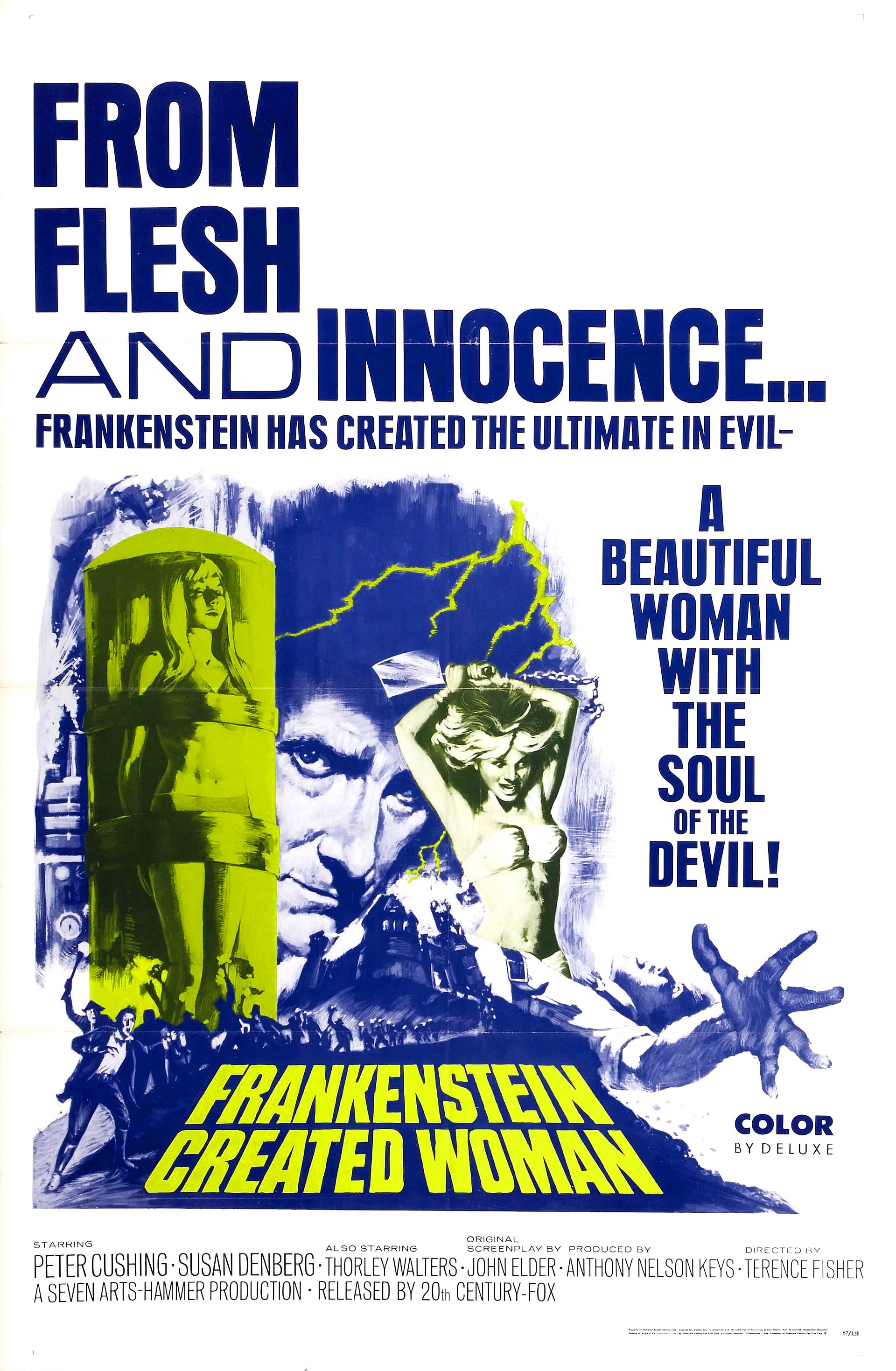

Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon. We’re continuing our exploration of Peter Cushing’s six Hammer Frankenstein films with the fourth installment in the franchise, Frankenstein Created Woman (1967).

As Brittney-Jade points out over at Day of the Woman, Cushing’s Baron Frankenstein is really a peripheral character in this tale of love and loss, seduction and revenge.

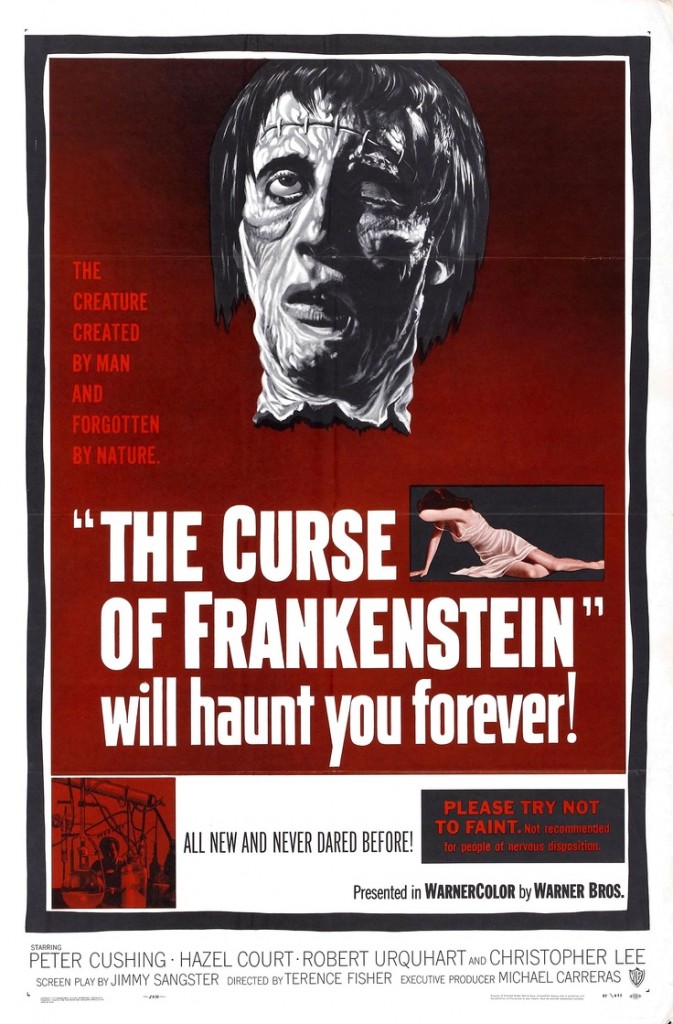

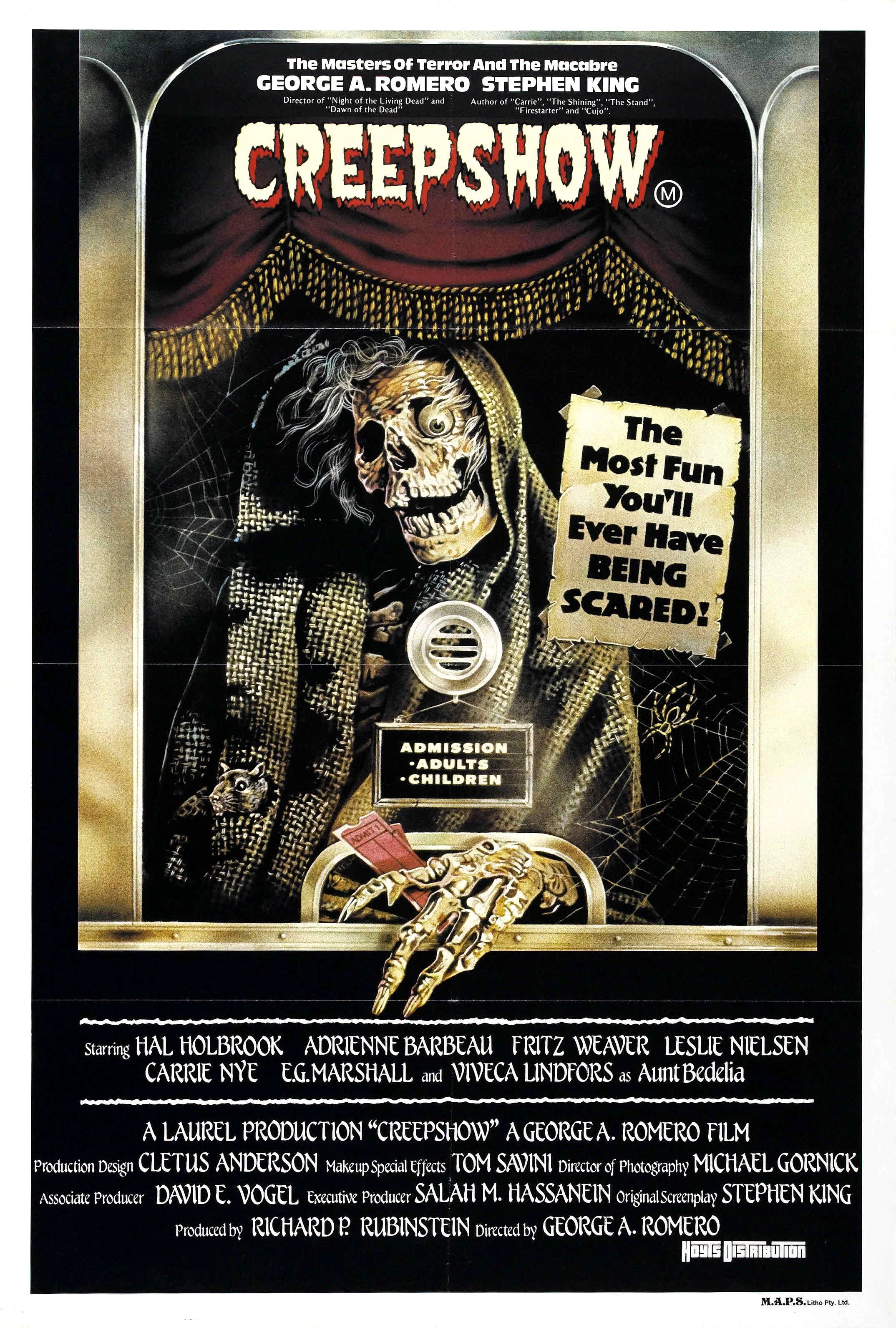

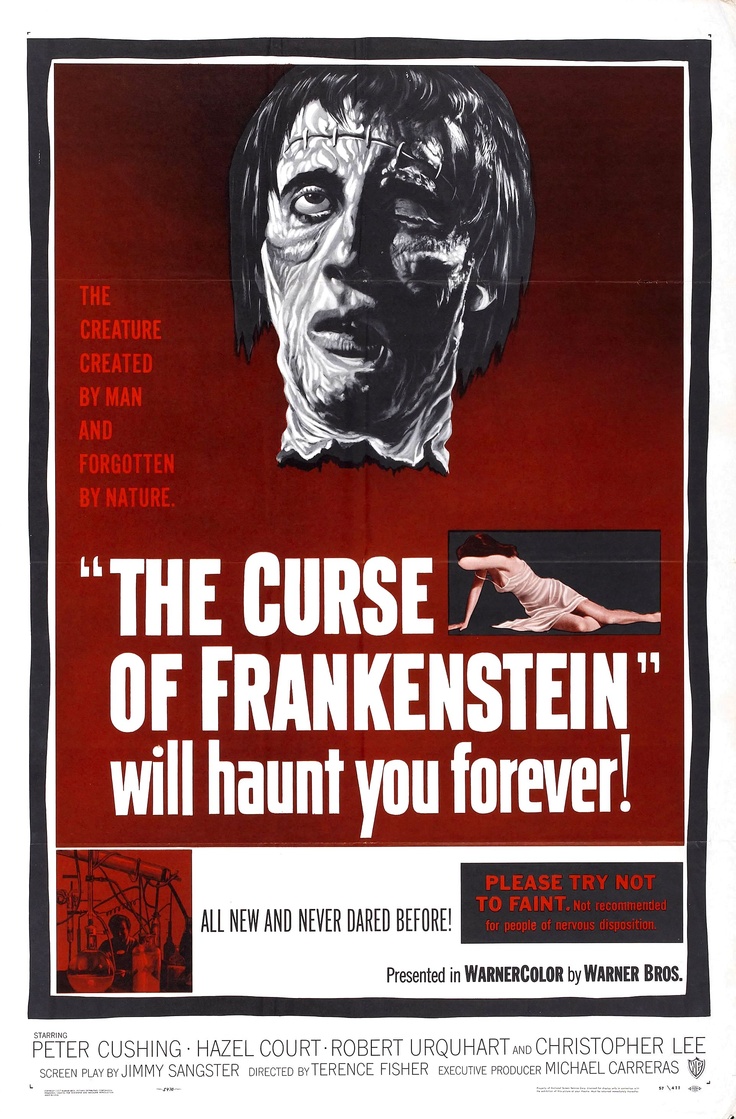

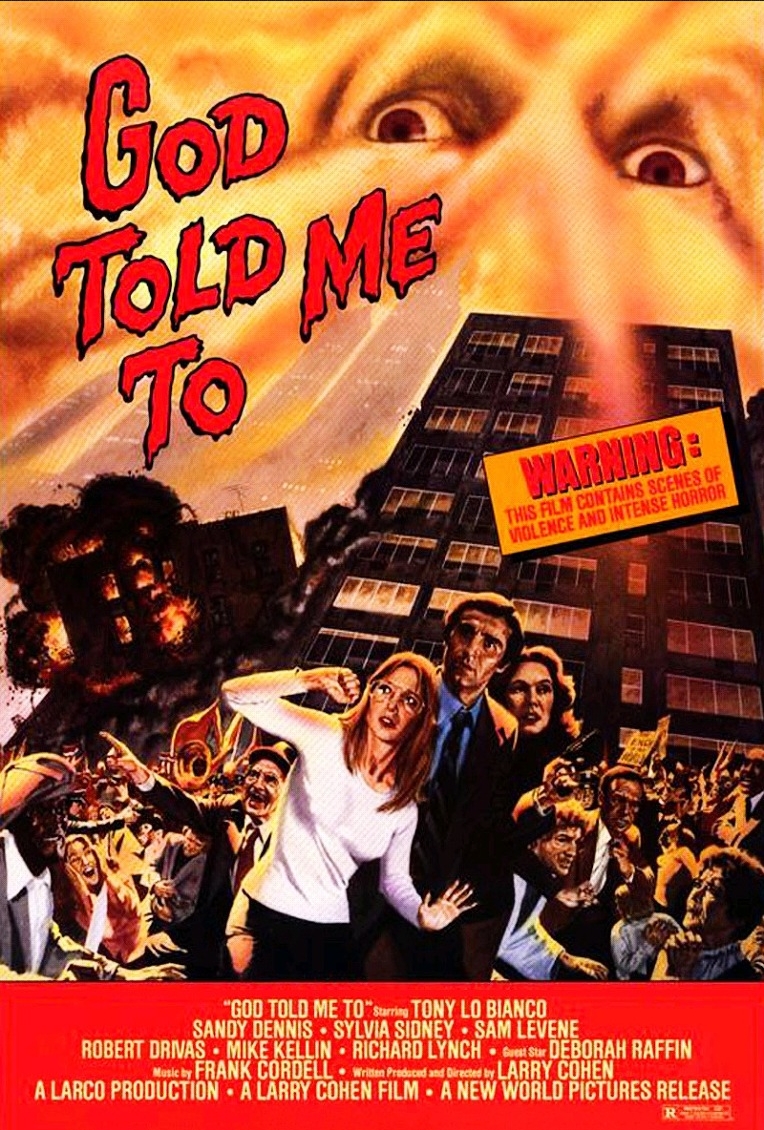

Nearly ten years since The Curse of Frankenstein took theaters by storm, Peter Cushing returns to the role that put Hammer Horror on the proverbial map. In that time, “The Gentle Man of Horror” had also made quite a name for himself at Hammer, Amicus, and elsewhere. The title Frankenstein Created Woman predates actual filming by a good bit and was derived from Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman (1956), the film that made his wife Bridgitte Bardot a star and led to the coining of the phrase “sex kitten”.

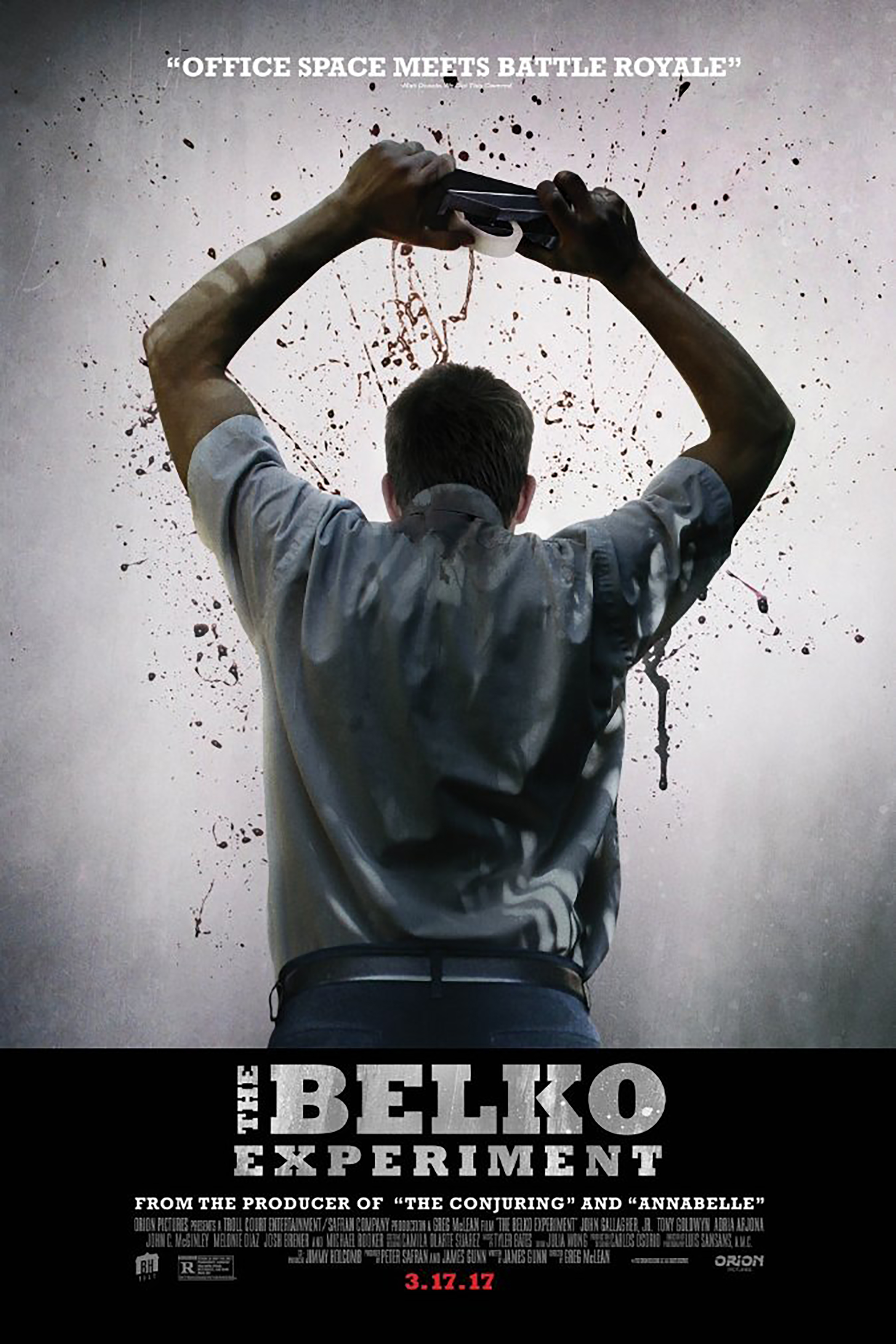

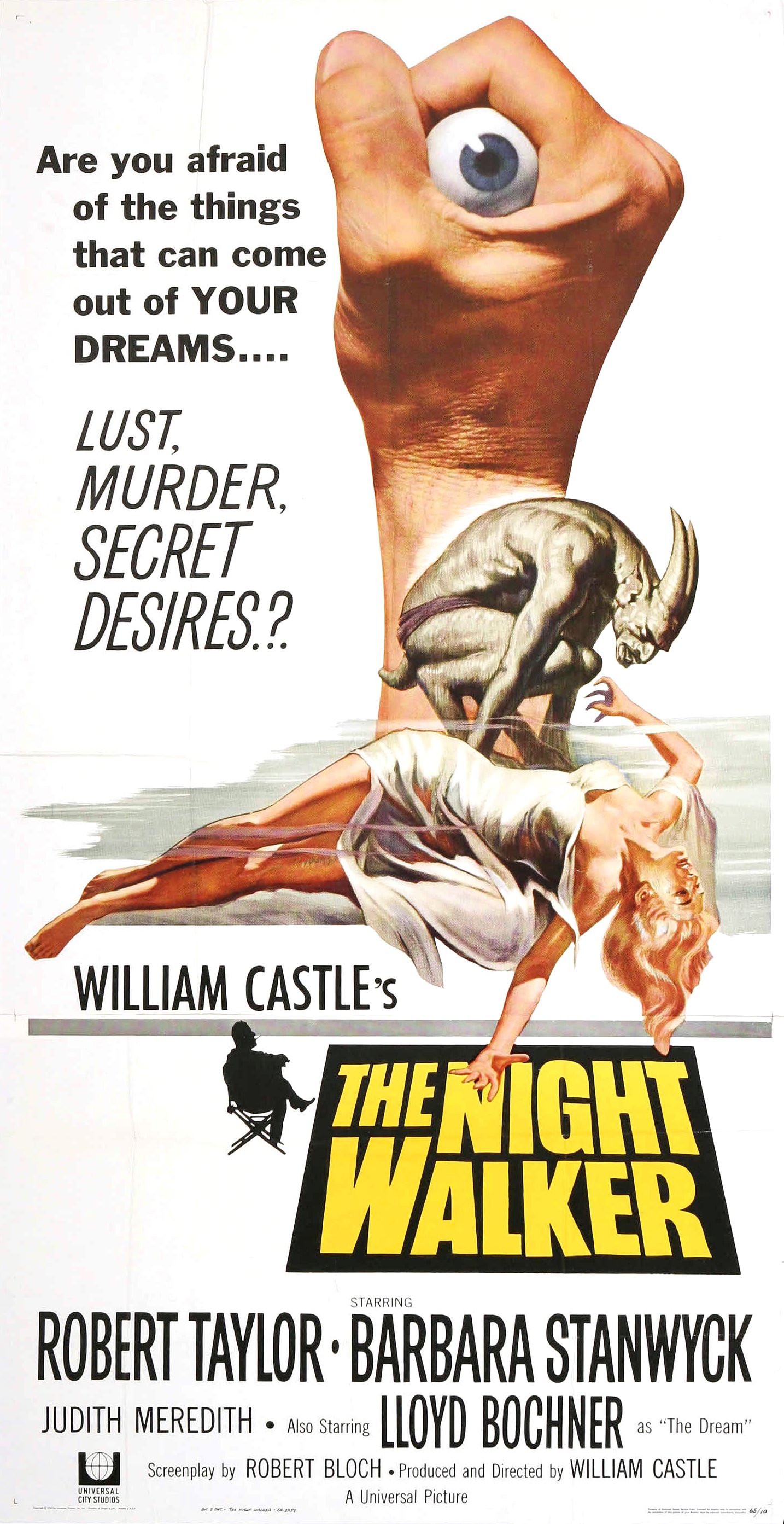

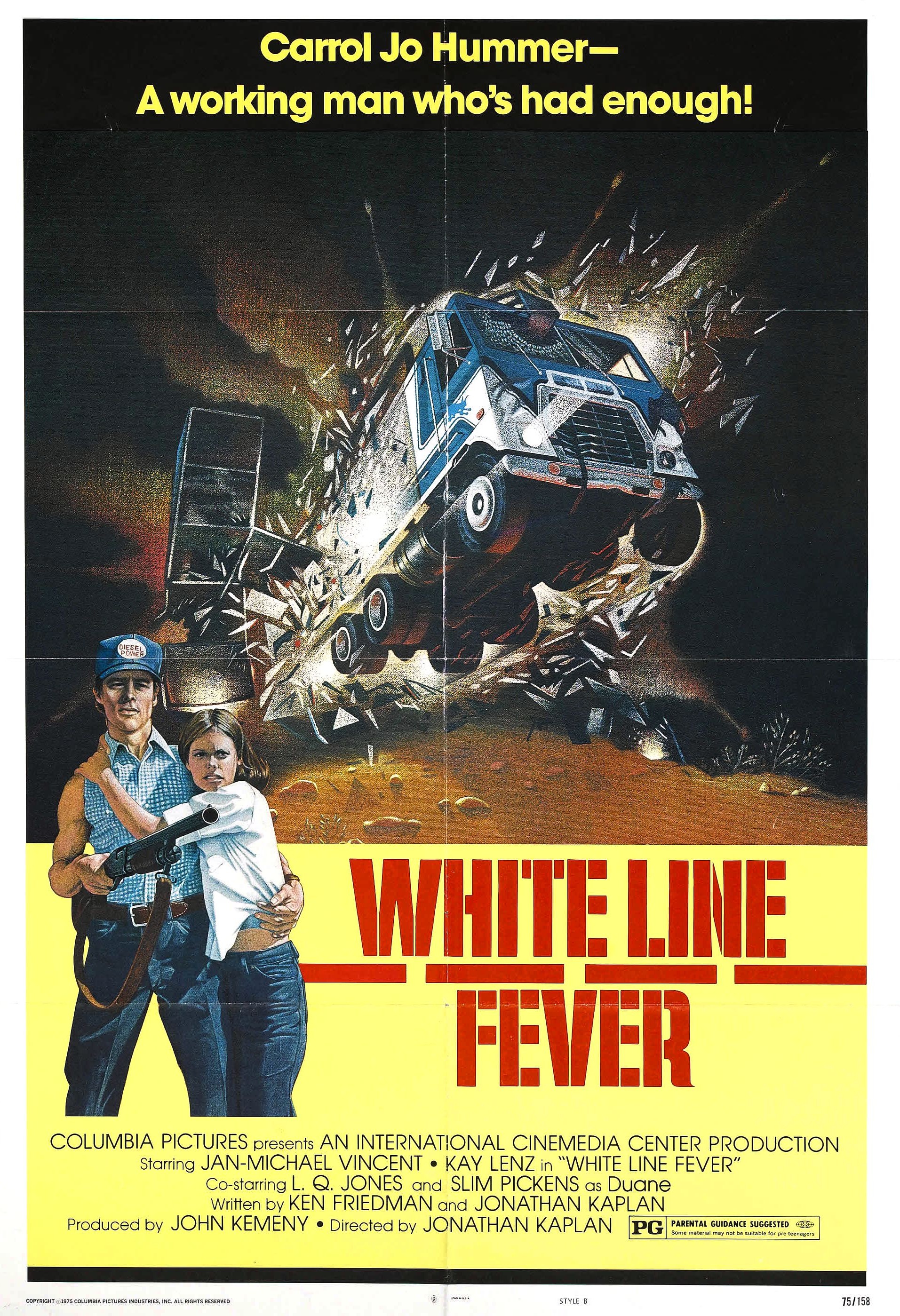

With a series of provocative promotional photos such as the one below, containing staged scenes not included in the film, Hammer seemed to have set out to create their own sex kitten in Susan Denberg. Denberg was Playboy’s Playmate of the Month for August, 1966 and a finalist for Playmate of the Year 1967. Like many models, she expressed her desire to enter the acting field.

Anthony Hinds, again as John Elder, returns to script with Terence Fisher taking the directorial reigns back from Freddie Francis. Fisher returns to his roots with limited sets and a small cast that put the story first and foremost. He would stay in the director’s chair for the remainder of the Hammer Frankenstein films.

Frankenstein Created Woman (1967)

As the film opens, we find ourselves returned to the shadow of the guillotine, a theme Fisher had established through the first two entries in the series. Duncan Lamont, the Police Chief from Evil, returns here in a very different role, albeit brief, as the condemned man. Accused of murder, he is drunkenly defiant and unrepentant until he notices his young son looking on from the distant treeline. He screams for his boy to turn away, begging his captors not to execute him in front of his son, but he has already lost their sympathy. The decapitation is indelibly burned into the boy’s mind and, as we will discover, it haunts him his entire life.

We find the grown Hans (Robert Morris) working alongside Dr. Hertz (Thorley Walters) on a timed experiment. At the count of one hour exactly, the two open a refrigerated chamber in their laboratory and pull out a long iron box. When the iron box is opened, its contents are none other than Baron Victor Frankenstein. Once he is resurrected by Hertz, his experiment is declared a success, proving that the soul does not exit the body immediately upon death, but lingers for at least an hour postmortem.

Hans and Hertz are an interesting pair of henchmen. Hans suffers under the social stigma of being a murderer’s son known for his own ill temper. Hertz serves as Victor’s hands. The Baron’s own are twisted and burned, presumably in his escape from fiery doom at the end of The Evil of Frankenstein (1964), and he wears sinister black gloves over them. Hertz appears to steady his hands with judicious slugs of cheap brandy and makes reference to his role as the village’s only physician being the sole reason for even modest success.

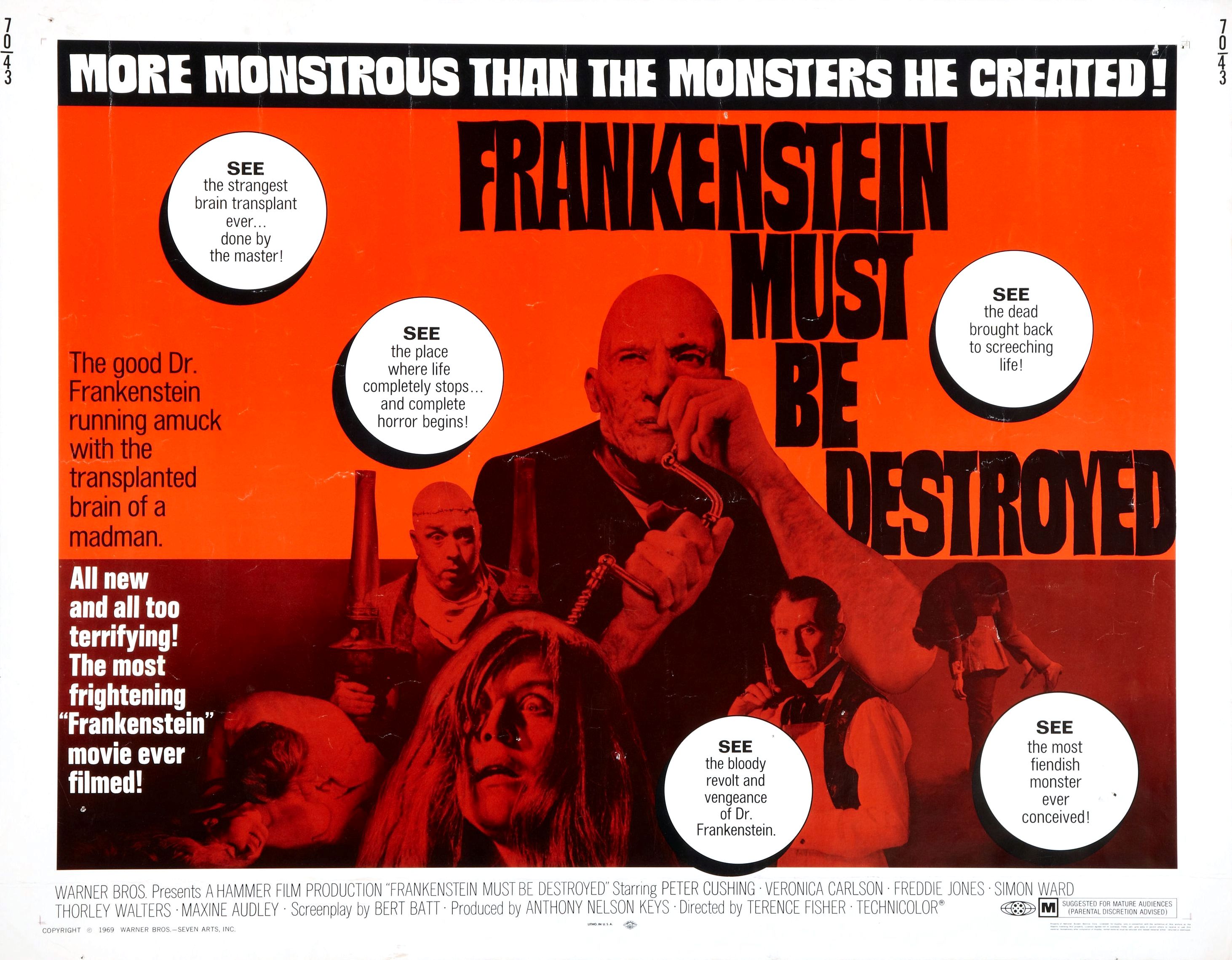

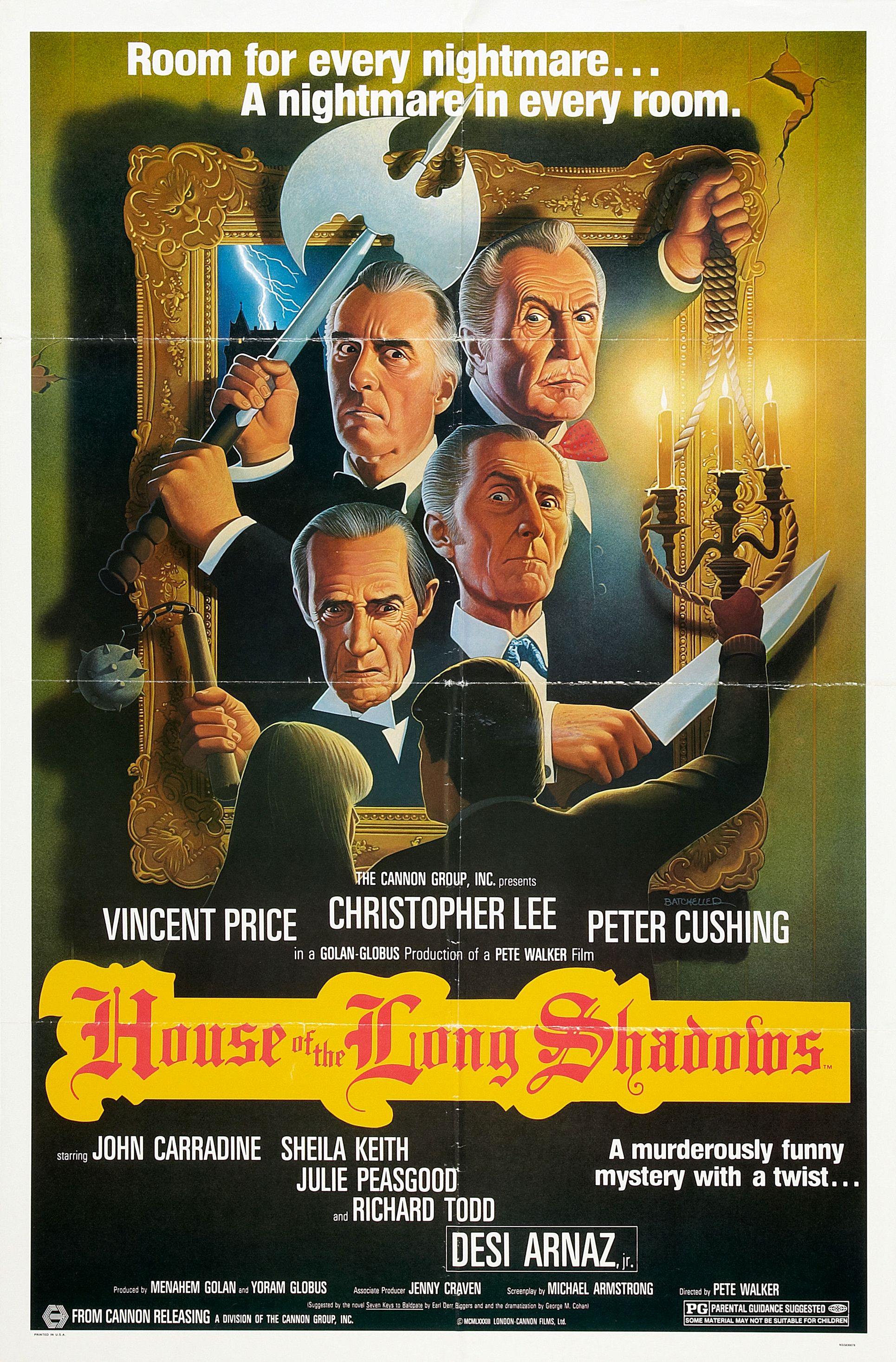

Frankenstein Created Woman father and son Duncan Lamont and Robert Morris went on to team up for Hammer’s Quatermass and the Pit (1967). While Thorley Walters worked with Cushing previously in the non-Hammer thriller The Risk (1960), there are also a couple of notable near-misses. He played Dr. Watson in Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace (1962), but with Cushing’s pal Christopher Lee as Holmes and not Cushing. His Renfield clone Ludwig serves Lee’s vampire lord in Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966), but Andrew Keir’s Father Sandor opposes Drac in that outing instead of Cushing’s Van Helsing. We’ll see more of ol’ Thorley when he returns in a different role for Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969).

Hans is dispatched to the local pub to secure appropriate beverage for celebration, and this is our first introduction to Denberg’s Christina. The image is a surprising one, especially to those drawn in by the film’s promotional materials. Barmaid Christina is scarred, disfigured, and partially paralyzed, in an even sadder state than poor Karl from The Revenge of Frankenstein. As we gradually discover, she is also Hans’ secret lover, each able to see beyond shallow village judgments to the beauty within the other.

Those village judgments are personified in the form of three young well-born rakes out for a bit of mischief. They taunt Christina and her father, the barman, until it proves too much for short-tempered Hans. A brawl ensues in which Hans gets the better of all three dandies, scarring ringleader Anton (played with wicked relish by Peter Blythe). Hans makes the fatal mistake, however, of threatening Christina’s father when the barman breaks up the fight upon the arrival of the authorities.

The three fops come back for revenge later that night and matters quickly escalate until they beat the barman to death with their walking sticks. Given Hans’ reputation, he makes the perfect patsy. He is summarily arrested the moment he stumbles upon the crime scene.

The subsequent trial is the standout scene in the film for me and features some great work by Cushing. The first is yet another example of his stagecraft as he absent-mindedly thumbs through the Bible he’s been sworn in on. He acts as if it’s the first time he’s seen one and is unimpressed, despite his current obsession with the immortal soul. The second is an exchange with the rakes who try to add witchcraft to Victor’s stated list of credentials. Frankenstein argues that while a doctorate is not offered in that field, if one were, he would surely qualify. Great stuff.

Hans refuses to damage the modesty of Christina with his alibi, seeing as he was in bed with Christina at the time of the murder. In spite of the friendly testimony from Baron Frankenstein, Hans is convicted and sentenced to the guillotine just like his father before him. Out of town to visit a doctor during the trial, an excited Christina returns just in time to witness the blade’s fall.

Victor and Hertz have already procured the head and body of Hans to capture his soul when grief proves too much for Christina, and she drowns herself in the river, providing a convenient vessel. The bulletproof force field used to contain the soul, represented here by a ball of light, may be too much for modern sensibilities, but I find it appropriate to the Victorian era. It’s no hokier than the “science” depicted in such period fare as At the Earth’s Core (1976). It reminds me of the 19th century science fiction of Nathaniel Hawthorne, such as “The Birth-Mark” or “Rappaccini’s Daughter”, both being concerned with the pursuit of artificial perfection.

Indeed, Victor and Hertz take the opportunity to “fix” Christina, transforming her into a blonde Bavarian beauty. Frankenstein calls the hair a side effect, but I think the title of this post hews closer to home. There is also a bit of bitter irony that while traveling the countryside and nearly bankrupting her father in search of a doctor who could help her, a capable and willing, if morbidly insane, candidate who is able to accomplish it as an afterthought can be found right in her home village.

This was not the first time Denberg played a character with an artificially enhanced physical appearance. In the Star Trek episode “Mudd’s Women” (1966), she plays Magda Kovacs, a “mail order bride” benefiting from the use of the “Venus pill.” While the rest of “Mudd’s Women” wore make-up to depict their character’s unenhanced appearance, Denberg merely had her hair tousled. It may have been at her request, but I’m not sure that it’s a flattering implication.

Even with Hans’ soul now residing in the bombshell body, Christina is largely a clean slate post-op. Frankenstein isn’t too forthcoming in helping her with her identity crisis, distracted as he is by the metaphysical aspects of his experiment. Hans’ severed head becomes a source of sinister direction, and through her, he begins taking his revenge on the three spoiled dandies.

This is new ground for the Frankenstein films, as Christina’s appearance draws her victims in rather than having them run for pitchforks and torches to assault the abomination. Hans knows just how to use his newly acquired assets to bait his traps while Christina was always uncomfortable in her own skin. The kill scenes are surprisingly lush and lurid, evoking the work of Mario Bava rather than James Whale or even Terence Fisher’s usual style.

Some are put off by the sequence of the kills, preferring instead if Christina had built up to the murder of ringleader Anton rather than dealing with him first. I believe the order is a conscious choice, and shows that Hans’ thirst for vengeance was not so easily sated until all three were dead. Avenged, he departs Christina’s body and leaves what remains of her own soul to bear the murderous guilt.

Once more it proves too much for Christina, and before Victor can stop her, she throws herself off a cliff back into her watery grave. The closing moments, the look on Victor’s face, can be interpreted either as sympathy for the young lovers or regret at another creation slipping through his fingers into oblivion. Given Cushing’s range, I like to think it’s both.

While clearly upstaged by the brief but memorable appearances of Cushing’s Frankenstein, Denberg surprisingly holds her own. Although her thick Austrian accent forced Hammer to dub her dialogue, she turns in a great performance as both the disfigured Christina and the vessel of vengeance, changing her body language to suit each aspect. Terence Fisher shows great restraint in not overly exploiting her, to the disappointment of many, I’m sure, and she remains sexy and sultry but believable as a murderess.

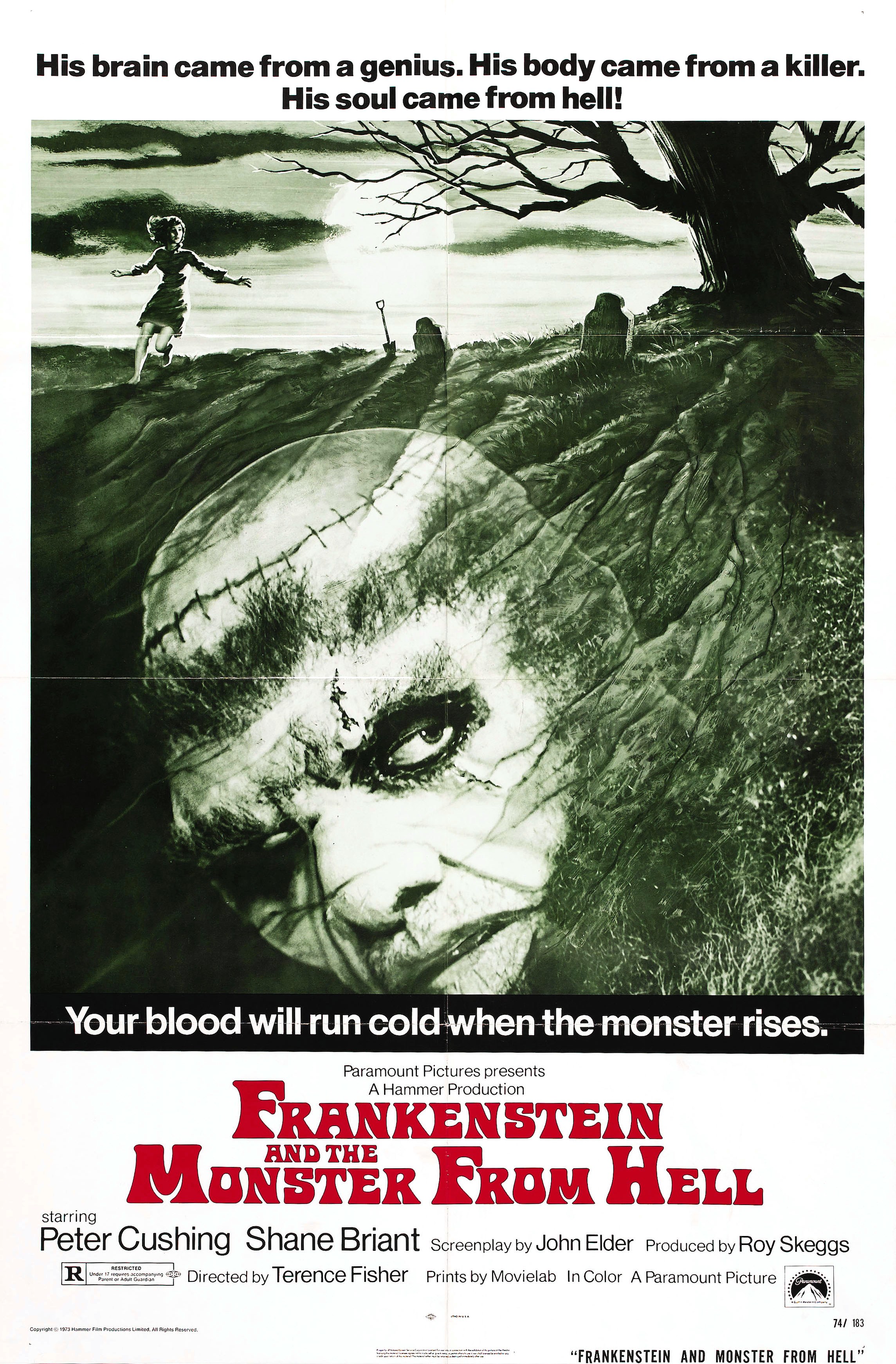

I would also be remiss if I didn’t encourage you to click the badge above to check out all of the myriad offerings in the Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon. There are some great articles, amazing art, music videos, interviews, and more. We’ll be back tomorrow to bring our little journey to its conclusion as we look at Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969) and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974). We hope to see you here!