“…Is but a dream within a dream.”

– Edgar Allan Poe

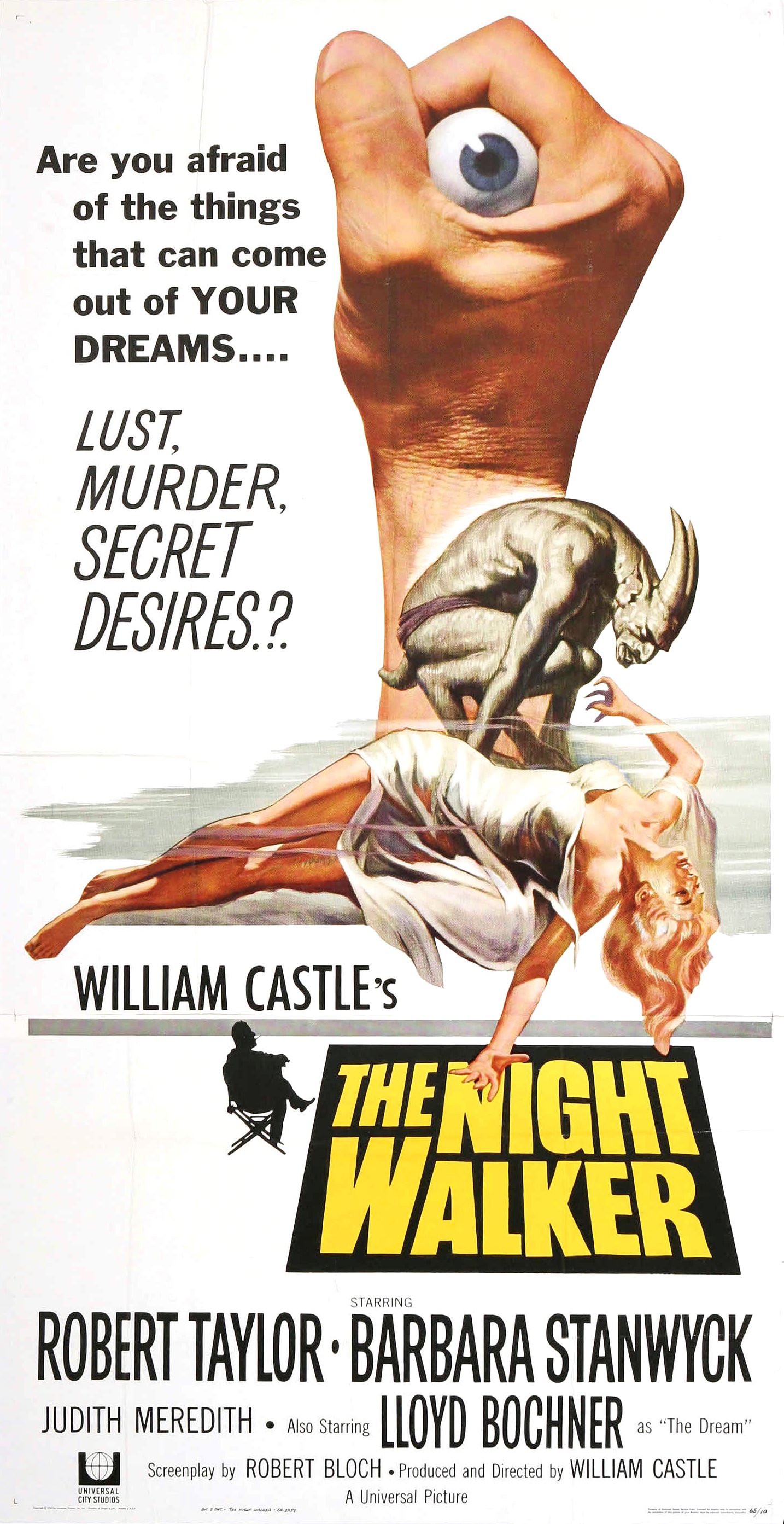

Dreams are the source of inspiration and terror in William Castle’s The Night Walker (1964), starring Barbara Stanwyck. The Night Walker stands as a milestone at the end of an era. It was the last black and white theatrical feature released by Universal and the last feature film in Barbara Stanwyck’s long and storied career.

The Girl with the White Parasol is hosting the Barbara Stanwyck Blogathon this week, and I’m proud to be participating with our little discussion today. Be sure to check out some of the other offerings at the link. Stanwyck had an incredibly diverse film career, and there’s sure to be something for everyone.

“A man is not old until regrets take the place of dreams.” — John Barrymore

In the late 1950s through the mid-1960s, Director/Producer William Castle was primarily known for his promotional gimmickry, often so outrageous that it overshadowed the films themselves. For The Night Walker, he attempted a more sedate approach, focusing attention on the pedigree of his screenwriter and stars.

Robert Bloch was already well known as the writer of the novel Psycho, adapted by Alfread Hitchcock into a wildly popular, record-breaking thriller. The success of the film led Bloch to move to Hollywood, racking up assignments in the wake of the Writers Guild strike. The Night Walker was Bloch’s second screenplay for Castle, after having written the Joan Crawford vehicle Strait-Jacket (1964) earlier that year.

A recurring theme throughout this period of Bloch’s oeuvre is the focus on psychological terror rather than supernatural bugaboos. His characters are often afflicted with a mental condition that makes their perceptions suspect if not outright delusional, and can be used to direct the actions of either antagonist or protagonist. Barbara Stanwyck plays our distressed protagonist in The Night Walker, a wealthy woman whose recurring dreams turn dark and potentially deadly after the untimely death of her blind and jealous husband (Hayden Rorke).

Stanwyck’s failed marriage to co-star Robert Taylor formed another angle for Castle’s publicity efforts. An Associated Press news story describes a Universal Studios party held in their honor on May 5, 1964 to promote the film. Stanwyck was asked if she had any objection to re-teaming with her ex-husband. “Of course not,” she said, “but you’d better ask Mr. and Mrs. Taylor.” Robert Taylor reportedly said “It’s all right with me if it’s all right with her.” By contrast, when Taylor’s then-current wife, German actress Ursula Thiess, was asked as well, she replied with “Not necessarily.”

Stanwyck and Taylor first collaborated on His Brother’s Wife (1936), a melodrama chock full of love, loss, betrayal, mobsters, and spotted fever. The film couple soon began living together, setting the rumor mill spinning. They reunited a year later for This Is My Affair (1937), with Stanwyck and Taylor reprising the moll and honorable man roles, respectively, but substituting bank robberies for jungle fevers.

By 1939, despite Stanwyck’s reticence in the aftermath of one deceased fiancé and one failed marriage, MGM insisted upon their wedding with studio chief Louis B. Mayer personally arranging the event. Their marriage lasted a little over a decade until Taylor filed for divorce in 1950 for unspecified irreconcilable differences. The chemistry between the two leads in The Night Walker is palpable and contains just enough grit and tension to give it depth without devolving into bickering or swooning.

The Night Walker (1964)

We open with a five minute reading from the “Book of Dreams”, voiced by the accomplished voice actor Paul Frees and accompanied by Twilight Zone-style visuals. If you have ever asked yourself the question, “What do The Manchurian Candidate, The Abominable Doctor Phibes, and Nestor, the Long-Eared Christmas Donkey have in common?” the answer is Paul Frees. With over 300 performances over 4 decades, most of them uncredited voice-overs, Frees was beyond prolific and sets the tone very effectively here.

After our introduction, we find blind millionaire Howard Trent (Hayden Rorke) and his attorney Barry Morland (Robert Taylor) talking over brandy. In the face of a world composed almost exclusively of sound, Trent has begun recording his surroundings. He has caught his wife Irene (Barbara Stanwyck) talking in her sleep, having the same dream night after night, and believes it suggests an affair. This leads to some none-too-subtle accusations that Barry might be the dream man in question.

After Howard Trent retires to his upstairs laboratory, Irene confides in Barry and, while insisting upon her innocence, she also flirts shamelessly with him before he leaves. This just seems to confirm Howard’s suspicions, and he confronts her directly afterward on the stairs. Tired of his jealousy, she just lays into him.

“I know why my dreams seem real, because when I’m awake my life with you is like a nightmare!” Howard demands the truth, but he clearly can’t handle the truth. “All right, here’s the truth! My lover is only a dream, but he’s still more of a man than you!”

Outraged, Howard assaults her viciously with his cane until she flees the mansion. Inexplicably, smoke begins rolling out from under the door to his laboratory. After he enters, shutting the door behind him and obstructing our viewpoint, an explosion rocks the house.

The next day, Irene is questioned by an arson investigator. Howard’s remains were not found, and the investigator chalks it up to the intense heat. He condemns the lab as unsafe and padlocks the door to what is now a crime scene.

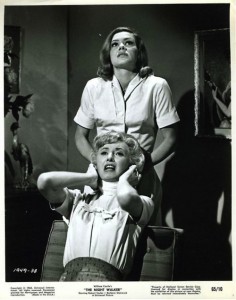

A clacking noise, reminiscent of Howard feeling his way along with his cane, disturbs Irene’s sleep. She gets up and wanders the house, calling his name. Noises draw her to his laboratory, now curiously unlocked and filled with smoke. The door slams shut, seemingly of its own accord. Unable to see through the dense smoke, Irene feels her way to the door and is horrified to find Howard’s burnt, motionless body alongside it. She screams in terror and revulsion. As her screams turn to choked sobs, he begins slowly walking, stalking towards her, tapping with his cane. Pretty chilling stuff. Stanwyck has an impressive shriek, worthy of a “scream queen”.

Irene awakens, confused, and throws on her robe. She rushes to the lab to find it soundly padlocked. It was all a horrible nightmare.

She drives over to Barry’s office for the very first time. He’s been going through Howard’s files. Irene wants to sell the house, but Barry indicates that it’ll take six months to go through probate. She can’t wait that long. She tells him about her nightmare and vows to move out that very day if she can’t sell it. She still owns a beauty shop with an apartment in the back where she used to live and decides to relocate there for the time being.

There, new employee Joyce (Judi Meredith) has seen to Irene’s apartment, setting up her furnishings and wardrobe. Irene tries to get comfortable, but it’s clearly no longer the home she remembers. Lying down exhausted, she falls fast asleep.

A tapping awakens her, but this time it’s different. A voice calls her name from outside the curtained window, pleading for her to let him in. We meet her recurring dream man (Lloyd Bochner), in suit and tie. He enters, a wry smile on his lips. “Surely you’re not afraid, not of me? We know one another too well for that.” He takes her in his arms, pulls her close, and kisses her.

“You have been warned!”

A worried Joyce wakes her at eleven, having let her sleep in all morning. Joyce tells Irene that Barry Morland has requested an appointment. He left a message that he’ll pick her up at six.

At a swanky jazz club, Barry and Irene talk over dinner. She puckishly inquires about his personal life, and Barry gamely plays along. Irene then tells him about her dream visitor. When Barry suggests a psychiatrist, Irene is insulted. A flaming kebab skewer halts her in her tracks, and she’s surprised to find herself suddenly pyrophobic. Barry drops all pretense and plainly asks if she murdered Howard, earning an indignant slap across the face.

Just after midnight, Irene takes some pills and tries to get some sleep though she’s clearly still distraught. Her mystery visitor wakes her up with his deep, sonorous voice. “Better hurry, it’s past nine.” A glance at the clock reveals it’s 9:20 to be exact.

After some champagne and banter, he takes her to a chapel, ignoring her pleas to head back. “We can’t. They’re all waiting.” When she asks who is getting married, the shocking answer is that they are. “You and I can do anything we like.”

Irene is appalled to see the priest and witnesses are actually all wax mannequins, even though she can hear the priest’s voice quite clearly. Despite never saying “I do,” the ceremony proceeds just as if she had. Once the ring is on her finger, the chandeliers start spinning and everything takes on a somber tone.

She rushes to the door and manages to pull them open, only to be confronted by a burned Howard. She retreats, screaming and shouting “No!” in denial. The ceremony is repeated, with Howard now serving as the groom. Instead of “I do” or mute silence, Irene’s reaction this time is a blood-curdling scream.

She seems to awaken, only to find her dream man looming over her. “I can’t wake up!” she sobs.

I found the whole sequence to be creepy and effective in that subtle fashion that has seemingly gone out of style. I’ve long argued that just a touch of the inexplicable added to the mundane taps into the purest terror. Movie monsters and cackling madmen, while often entertaining, tend not to unnerve me, but put something seemingly innocuous where it should not, could not be, and I’m shivering. Mannequins clearly don’t belong in wedding chapels. It also doesn’t hurt to have a top-notch actor or actress sell the piece, and Stanwyck’s growing anxiety is surely contagious.

The next day, Morland comes to check on her and apologize. They reconcile over some coffee, and she asks for his help with her nightmares. She recalls a landmark from her trip with the mystery dream man, a statue of a woman spinning on a silver dollar. If anyone has any idea what landmark this may have been from, please comment below. I couldn’t find hide nor hair of it anywhere.

Anyway, they manage to locate the apartment where her mystery man first took her for champagne, convincing Irene that it was no dream. All of the furnishings inside are covered, however, and the paintings on the wall are all gone. “It all looks so different, so un-lived in.”

Barry lets her in on the fact that her deceased husband Howard owned the apartment in question. When questions put to the landlady fail to identify her mystery beau, Irene starts to question her sanity. She and Barry next try to locate the nightmare chapel.

They find it, also vacant, as well as condemned and up for lease. Barry uses the leasing option as a pretense to get the groundskeeper to let them in. Just as she’s about to give up convincing Barry of the reality of her visions, Irene finds the wedding ring lying discarded on the floor.

What is real, what is dream? Who is alive and who is dead? Such are the questions facing Irene Trent and, by extension, the viewer. I’ve probably given far too much away already, but I’m not going to spoil the last third of the film, which unravels the twists and turns to provide largely satisfying answers to those queries.

Ms. Stanwyck isn’t the only one bringing their A-game to what was traditionally B-material. All of the performances are exceptionally tight, with Robert Taylor and Lloyd Bochner anchoring the film on either side of Stanwyck’s Irene Trent, bookending her character with reality and fantasy, respectively. Bochner had previously starred in the iconic Twilight Zone episode “To Serve Man” (1962) and headlined the King Solomon’s Mines rehash Drums of Africa (1963) with Frankie Avalon. He manages to be at turns seductive and menacing, aloof and enigmatic. By contrast, Taylor’s Barry Morland is earthy and pragmatic, a lawyer to the core, but drawn to the frantic widow perhaps despite his better judgment.

The set design is also worthy of distinction. While most of the set pieces have that staged feel of studio-bound dramatic film and television productions, some of the choices highlight rather than hinder the script. From the Trent mansion, with a wall covered in ornate clocks, all ticking and chiming in unison, to the beauty parlor, all functional and sterile, and, of course, the chapel, sparse and Kafkaesque, shot from rapidly changing angles to disorient and unnerve.

Lastly, a word about the music. Some have stated elsewhere that the title theme does bear a striking resemblance to “Food, Glorious Food” from Oliver!, but overall, the bombastic score by The Addams Family composer Vic Mizzy does its part. I found any chuckling it invoked to be WITH the film, rather than AT it. In a 2009 interview, Mizzy tells of a screening of the film at the Hitchcock Theatre for Universal Studios chief Lew Wasserman where Wasserman only gushed to William Castle about the score.

Now, admittedly, before viewing this film, I had only seen Ms. Stanwyck as the quintessential femme fatale in Double Indemnity (1944). Still, it’s such a memorable performance that I knew there was more to Ms. Stanwyck than an anklet, a strategically placed towel, and some breathy innuendo. I’m glad I was able to participate in the Barbara Stanwyck Blogathon, and many thanks to The Girl with the White Parasol for graciously hosting. If you’re looking to broaden your Barbara Stanwyck horizons, you couldn’t ask for a better opportunity than that link. Take a look, then feel free to come back and let me know what you’ve found. I’m always open to suggestions.

Until next time, then, folks… Sweet Dreams…

RayRay, this is a great review–I’m totally hooked and want to see Night Walker NOW!

Thanks,

Ivan

This sounds like a must-see! I didn’t realize Stanwyck and Taylor had done another movie together as late as 1964. Thanks for a great review.

Wow! This sounds almost too scary for me — but if I ever run across it, I’ll give it a try, for Stanwyck’s sake. Great review!

Ray- I’m sort of hooked on your site now!See you at the William Castle Blogathon fella-Cheers Joey

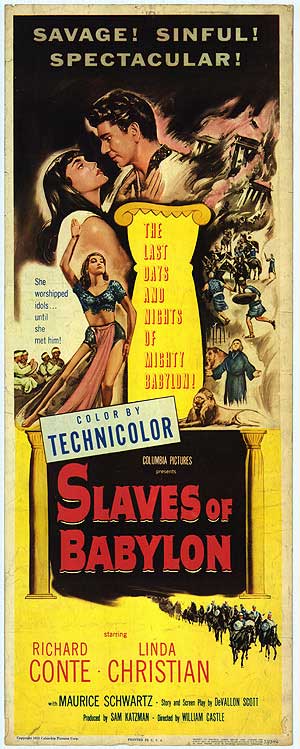

[...] at Weird Flix: Slaves of Babylon [...]

[...] at Weird Flix: Slaves of Babylon [...]

[...] at Weird Flix: Slaves of Babylon [...]

[...] at Weird Flix: Slaves of Babylon [...]

That shriek of Stanwyck’s–it’s like a soprano’s dying aria! I haven’t seen enough of Castle’s work to judge where this one rates but I can definitely say I wasn’t bored and I was always intrigued to see where it was going. I really appreciate that Castle didn’t treat Stanwyck like a camp object or a faded beauty queen. So many post-Baby Jane flicks really exploited older actresses and held them up to ridicule and this one doesn’t. My main qualm with the film is the whole “dream lover” angle. Mainly because it’s hard to imagine Stanwyck either fantasizing about or wanting this slick, weird courtship. So her passivity during the whole thing disturbs me; I keep expecting her to snap, “Can it, brother,” every time the mystery dream man starts yammering on. Still, the idea of being trapped in an endless, constantly shifting nightmare is pretty creepy and I find the chapel/mannequin scene horribly unsettling.

Cheers and thanks for a great contribution to the blogathon!

Thanks again for hosting!

I think the key to the whole “dream lover” scenario is in Irene’s enraged confession to husband Howard. She’s been the trophy wife for so long, locked up in that creepy manor, that any alternative is appealing. Any relationship between her and Barry (Robert Taylor) began as a figment of Howard’s jealous imagination, but she seems amenable to it once it is suggested. I think it’s intentional that she seems to have more chemistry with her former co-star Taylor than anyone else in the film.

Without giving the ending away, it becomes clear that her “dream lover” is more than her own sexual and emotional frustrations taken shape. Any shortcomings there are not a product of Irene’s or Stanwyck’s desires. I guess if the mystery man were more openly attractive, it would undercut the tone of menace that underlies his “yammering”. Agreed, though, that she plays a decidedly more passive character than her trademark femme fatales.

That would be an interesting intellectual exercise. Would this film work if the gender roles were reversed, perhaps with some older grande dame playing Taylor’s blind wife (remaining menacing without falling prey to the customary exploitation and ridicule) and Stanwyck as the edgy attorney? Hmm. I like that.