Welcome to Day Three of the

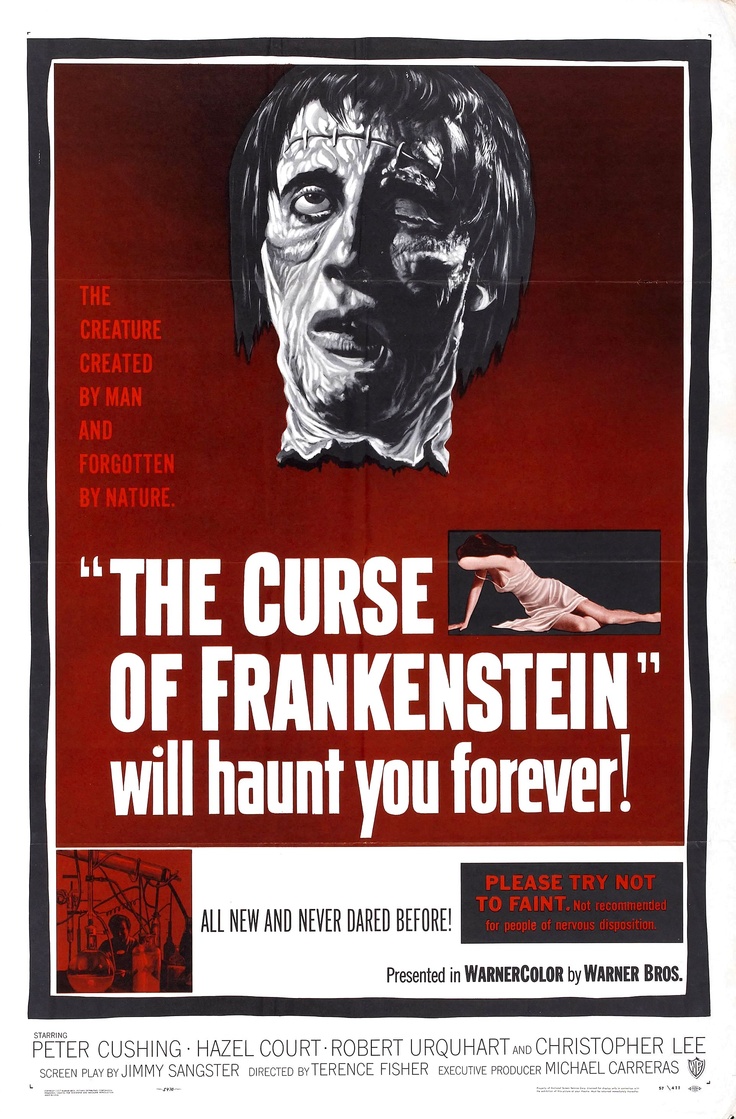

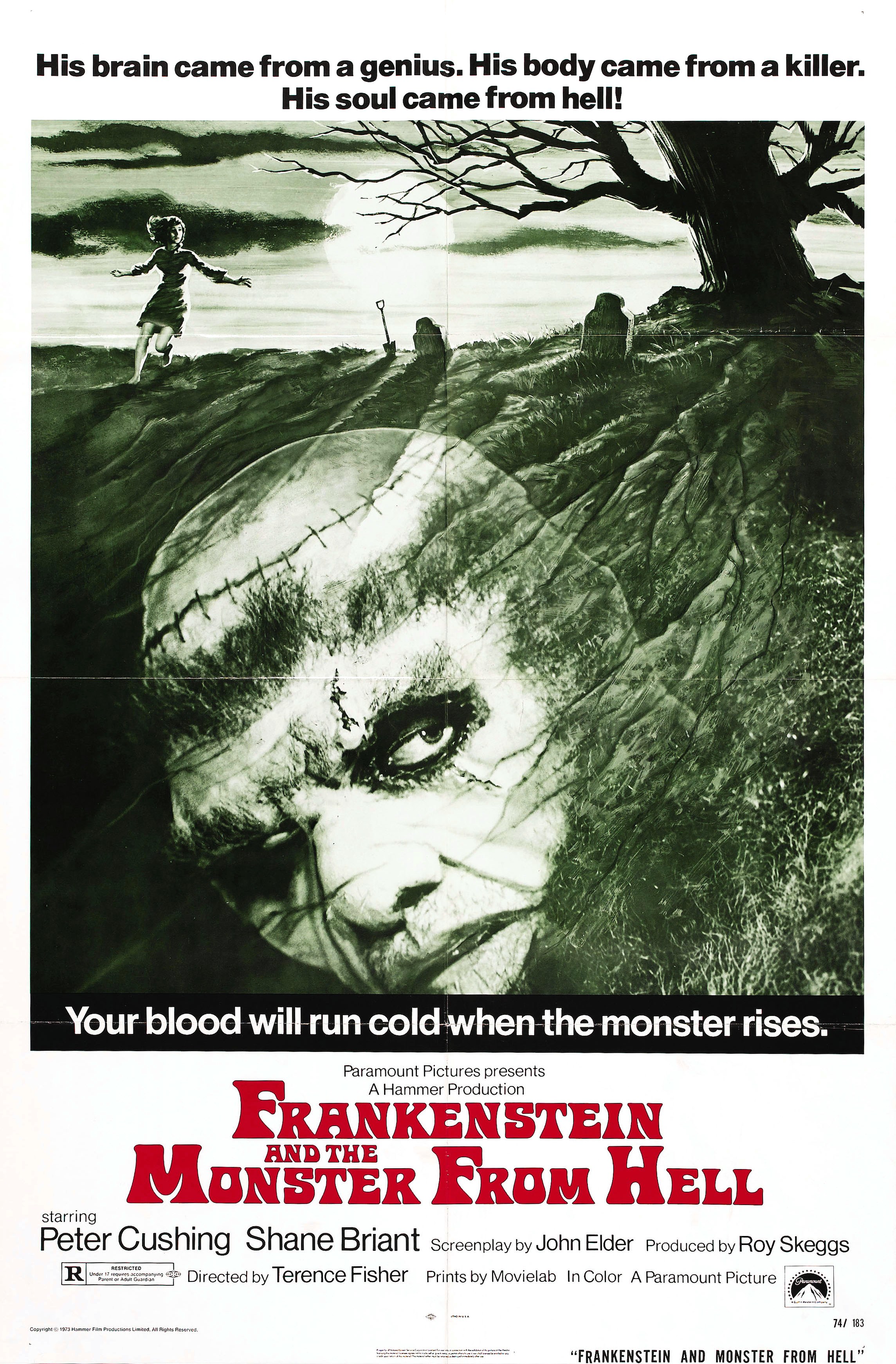

Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon. Today, we’re going to begin our journey through the six Frankenstein films starring Peter Cushing and produced by Hammer Films.

I’ve been a fan of the Mary Shelley classic Frankenstein since I first read it in my youth. The novel is a series of nested stories, starting with the journal of a North Pole explorer and including a tale told by the monster itself, but most of these are abandoned in adaptation for a more linear plotline. I also adore the Universal Pictures film from 1931, starring Boris Karloff and directed by James Whale.

It’s somewhat suprising, then, that I hadn’t seen any of the Hammer Films Frankenstein series until very recently. I had been aware of them, sure, and looked forward to watching them someday, but just never seemed to get around to them. I recorded three of them when they aired on TCM during last Halloween, but still they sat on my DVR, unwatched, until last month when Jon Kitley of Kitley’s Krypt issued a challenge to his Kryptic Army.

The April Mission was to confess to not having seen two “horror classics” and then remedy that. As a dutiful soldier, I chose The Curse of Frankenstein and its immediate sequel, The Revenge of Frankenstein. After a six day work week, they were welcome treats on a lazy Sunday afternoon.

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)

London-based Hammer Films had been cranking out “quota-quickies” for twenty years before The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) was a surprise sci-fi blockbuster. The spelling of the title was a very conscious choice, designed to take advantage of the newly created X certificate given to films of an adult nature, suitable for those 16 years of age or older, and roughly equivalent to the MPAA’s R rating. Even with the X certificate, Xperiment and its would-be sequel, X the Unknown (1956), caused quite a stir with censors because of their macabre subject matter and imagery.

American producers Max Rosenberg and Milton Subotsky had written a script for Frankenstein and the Monster and submitted it to Associated Artists Productions. a.a.p., negotiating to distribute Hammer films in the U.S., forwarded it on to them. Hammer was disappointed with the script and although the novel was already in the public domain, the script borrowed heavily from Universal’s Son of Frankenstein (1939).

Jimmy Sangster had been working for Hammer as an assistant director when his plot for a Quatermass sequel instead became the surprisingly successful Quatermass pastiche, X the Unknown. Despite protests that he was a production manager, not a writer, Sangster was commissioned to write The Curse of Frankenstein in an effort to move the film away from the old Universal treatments. Hammer was so impressed with the results, the project quickly transformed from a black-and-white quickie to a full color production. Though their Frankenstein and the Monster never materialized, Rosenberg and Subotsky would go on to found Hammer rival Amicus Productions, whose horror anthology films would make great use of Peter Cushing as well.

Sangster’s script may have impressed Hammer, but it didn’t fare well with the British Board of Film Censors:

“We are concerned about the flavour of this script, which, in its preoccupation with horror and gruesome detail, goes far beyond what we are accustomed to allow even for the ‘X’ category. I am afraid we can give no assurance that we should be able to pass a film based on the present script and a revised script should be sent us for our comments, in which the overall unpleasantness should be mitigated.”

Regardless, the script remained unchanged. Terence Fisher was tabbed to direct, having already worked with Hammer on some crime films and a couple of minor science fiction entries. Not wanting to be unduly influenced, Fisher avoided seeing the Universal Frankenstein film. Curse was the first time Fisher directed Cushing, but it certainly wouldn’t be the last. Peter appeared in 14 Terence Fisher films in all.

Cushing was chosen for the lead because of his work for BBC television, most notably in Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale’s controversial adaptation of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954). The film opens with Cushing’s haggard and imprisoned Baron Victor Frankenstein receiving a visitor. The priest was summoned by Frankenstein to hear his tale of murder and madness because the people will trust and listen to the priest, and that’s the only chance the doomed Baron has if his story is to be believed.

The Baron’s narrative, told in flashback, forms the basis for the rest of the film. We meet the Baron in his youth, played with smug confidence by Melvyn Hayes. Hayes, 22 at the time, appears far younger as the freshly orphaned Baron, heir to the title and his family fortune. The scene features our introduction to Victor’s young cousin Elizabeth. Played by the buxom “horror queen” Hazel Court (Devil Girl from Mars) for the bulk of the film, here she is played by Hazel’s own daughter Sally. Sally did not care for the acting experience, and this remains her only film credit.

We are also introduced to fresh-faced Dr. Paul Krempe (Robert Urquhart), interviewing for a position as a tutor. Krempe is surprised to find that the Baron and his prospective pupil are one and the same. While at first amused, Krempe sees the opportunity here, but later horrors prove he made a far better tutor in science than father figure.

Though his scene is brief (less than 3 and a half minutes of screen time), Hayes makes quite an impression as the young Baron. He is headstrong, demanding, and impatient, a boy made a man by the untimely death of his parents, and death would prove his great nemesis, not the villagers or authorities who come to fear and loathe him. Hayes had previously worked with Fisher on the Hammer crime film The Black Glove (1954). Though he shares no scenes with Cushing (seeing as how they play the same character), he would re-team with Cushing outside of Hammer Films in the crime film Violent Playground (1958) and the horror film The Flesh and the Fiends (1960).

The passage of years is reflected in the return of Cushing to the title role and the growth of Krempe’s facial hair. Their first great scientific achievement is the resurrection of a puppy. Victor’s gasp of “Paul, it’s alive,” is as close as we get at this point to the shrieking madman presented in the Universal version. The cute animal’s rebirth, amid non-maniacal joyful laughter, only subtly foreshadows the horror to come and subverts our expectations. This is happy, healthy, adorable science at work.

Krempe wants to publish immediately, to announce their discovery and benefit the world. A smug Victor sips brandy from a snifter. Here, he lets Paul do the shouting as he calmly, politely, coldly refuses to share their discovery. Restoring life is not enough for Victor. He wants to create life from nothing.

A hanged man provides the raw materials. The scene of Victor cutting the condemned man from the gibbet was the first shot for the film. This night crime forms our first truly horrific images. The music begins to take on a sinister tone as well. Paul’s concern grows as Victor grimly sets to work, heedless of the blood staining his noble finery. An acid bath, used to dispose of the corpse’s head, is not only a source of grisly sound effects, but functions as Chekhov’s gun, foreshadowing later events.

who experimented with the devil and was forever cursed…”

While Paul is nauseated and unnerved, the work makes Victor hungry. His appetites form a theme that runs through the film, his thirst for brandy coupled with a thirst for knowledge, his hunger for power over death, his lust for the maid Justine and for intellectual challenge. Cushing’s enthusiasm in the role is infectious, and makes some viewers uncomfortable as they root for a Victor Frankenstein that is darker and more selfish than other, more refined incarnations.

While Victor is off procuring the severed hands of an accomplished and freshly deceased sculptor, Elizabeth (Hazel Court) returns. Her exchange with Paul is pure confusion as she first confuses him for Victor (having last seen him as children), and then surprises Paul with the announcement that she’ll be moving into the manor, clearly something Victor neglected to discuss with his mentor turned lab assistant.

When Paul warns against the danger of Elizabeth discovering their activities, Victor doesn’t see the harm. He is blind to the horror he is wreaking in the course of his ambition. Justine, the maid and Victor’s secret mistress, is also less-than-enthused about Elizabeth’s arrival. Victor finds her jealousy amusing. Having grown up without adult supervision or rules, he is a petulant child with no sense of responsibility or accountability.

This is apparent in his murderous scheme to acquire a suitable brain, that of Professor Bernstein. As Bernstein and Frankenstein share brandy and cigars, the professor and Elizabeth try to show Victor the importance of family and fraternity. He is moved by Bernstein’s words of wisdom, but undeterred. He has come too far to turn back now and Bernstein’s fate is sealed with a shove.

In Bernstein’s crypt, Paul confronts Victor in the act of removing Bernstein’s brain. In the ensuing struggle, the brain is damaged, and Victor is distraught for the first time, not from having committed murder or losing a mentor and friend, but from having his plans derailed. Victor is forced to admit that he cannot finish his experiments without Paul’s help, and he resorts to subtly threatening Elizabeth to get his way.

During their discussion, a lightning strike triggers the apparatus and brings the creature to life. It’s nearly 50 minutes into the film before the bandages are torn away and we see the horrifying visage of Frankenstein’s Monster (Christopher Lee) for the first time. While Phil Leakey’s make-up may have been last minute, it lends a bloated, sloughed pallor to the creature that works well in color to indicate its necrotic origins.

If not for Paul’s intervention, creation would have strangled creator to death upon their first meeting. Ungrateful, Victor blames the creature’s murderous nature on the damage done to the brain by Paul. Soon, the monster is loosed on the countryside to murder a blind man and his grandson (the latter heavily implied off-camera). Victor promises to warn the villagers, but doesn’t. His chief concern is not their lives but that of his creation. Paul shoots the creature through the eye and everyone lived happily ever after.

Except Victor cannot let the dead lie. Upon his return to the manor, he is confronted by Justine, who reminds him of his promises to marry her. He laughs at her plight, her innocence and gullibility, both taken advantage of to periodically sate his primal lusts. She claims to be pregnant with his child, causing him to grow serious, but he tells her it would be easily blamed on any of a number of other villagers. When she ups the stakes by threatening to tell the authorities about his experiments, he dismisses her harshly. He is not moved by love or responsibility, but by the danger she poses to his work.

Justine sneaks into his laboratory that night, eager to find some proof of his criminal activities. She stumbles upon the exhumed creature, and Victor locks both the maid and his unborn child in to be murdered at the hands of his true creation. Victor blithely plays off her disappearance at a sumptuous breakfast with Elizabeth. “I expect some village Lothario eloped with her. She always was a romantic little thing.”

With his experiments in order, Victor leaves Elizabeth to plan their impending nuptials. Despite Elizabeth’s eagerness and obvious physical charms, Victor decides to work on the eve of their wedding. Paul arrives at Elizabeth’s invitation, and upon hearing from her that Victor’s work has resumed, immediately heads for the laboratory. There, Victor demonstrates his command over the creature, treating it like a dog, hearkening back to the puppy they first resurrected together.

Paul is horrified, but Victor is quick to share credit as well as blame for the results of their collaboration. Victor vows to continue until his determination is satisfied. Finally, Paul is left with no alternative. He must go to the authorities and tell them of their collective crimes.

Seeing Paul rush out with Victor in pursuit, Elizabeth is concerned. She heads to the laboratory to see what has distressed them so and finds the acid bath, mere moments before she herself is found by the hideous creature, broken free of his chains. It doesn’t menace her immediately, however, and, during his struggles outside with Victor, Paul has the opportunity to see the thing lumbering about the battlements. Victor rushes to fetch a pistol and confront the thing on the battlements, but both shots and the thrown pistol only serve to focus the creature’s rage on its creator. Victor sets the thing alight with a hurled lamp and watches with revulsion as it falls through a window into the acid bath.

We return to our framing device, with the imprisoned Victor miserable at the fruit of his labors. The priest is unconvinced, but Victor perks up at the announcement that Paul has come to call. Victor seeks corroboration from Paul, but Paul insists Victor is responsible for Justine’s murder (her body presumably found in the laboratory). With the monster dissolved and Paul and Elizabeth departed, Baron Victor Frankenstein is left to face the guillotine alone.

So much for five sequels, eh? Well, we’ll see that guillotine again tomorrow as we witness The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958). Be here or be square.