Terry’s Early Work

Terrance Quinn was born in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, on this day in 1952. While attending Central Michigan University, he took up acting as well as writing and directing for the stage. Finding a “Terrance Quinn” already registered with Actors Equity, he adopted the professional name “Terrance O’Quinn,” later shortening the forename to “Terry”.

Terry made a number of unremarkable television and film appearances in the early 1980s, including his feature film debut in the much-maligned Michael Cimino fiasco Heaven’s Gate. In an episode of the television series Tales of the Unexpected, he plays police officer Randy, who unwittingly takes a satchel full of stolen jewelry and negotiable bearer bonds as collateral for a $5.40 cafe check incurred by the panicked burglars. The ending is left purposefully ambiguous, so the viewer never finds out if Randy discovers the loot and what he chooses to do about it. It’s a fun little role, which leaves the requisite twist ending in Terry’s capable hands.

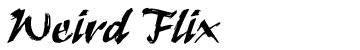

Silver Bullet

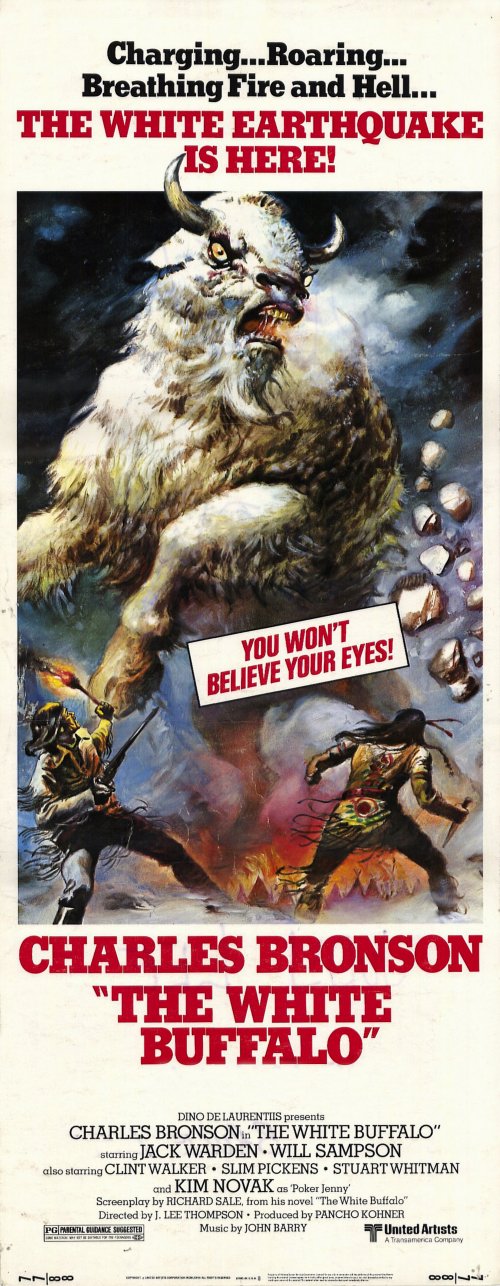

In 1985, Terry appeared in the film Silver Bullet as Joe Haller, Sheriff of Tarker’s Mills, Maine. The screenplay was adapted from the Stephen King novella Cycle of the Werewolf. The film was plagued with production difficulties, causing changes in script, director, and creature design, most at the behest of demanding producer Dino De Laurentiis.

Silver Bullet is the tale of a dysfunctional family in a dysfunctional town. The story is narrated by an adult Jane Coslaw (Tovah Feldshuh, with the younger version played by Megan Follows). It recalls her remembrances of a fateful year (1976) in which a series of murders ravage her home of Tarker’s Mills.

Marty (Corey Haim) is Jane’s younger brother, a paraplegic confined to a wheelchair. While Marty isn’t one to let his disability stand in his way, his can-do attitude really gets under the skin of his big sis, who is tired of being overlooked in favor of the golden child (“Marty, Marty, Marty!”; see “Marsha, Marsha, Marsha!”, Re: The Brady Bunch). This petty jealousy comes to a head when alcoholic Uncle Red (the pitch-perfectly cast Gary Busey) comes for his monthly visit. Jane takes perverse pleasure in pointing out Red’s flaws, his alcoholism and his string of failed marriages, to the crippled nephew who idolizes him.

Marty does have good reason to hold his uncle in such high esteem. Red replaced the usual muffler on his motorized wheelchair (“The Silver Bullet”) with a cherry bomb blast pack and has promised a new, custom wheelchair is already under construction. Of course, even Marty can see that Red’s promises have a bad habit of going unfulfilled.

The Coslow Family drama takes a back seat to a string of murders, starting with a railroad worker, a would-be suicide, and an abusive father. At the local watering hole, Owen’s Bar (named after Stephen King’s own son, Owen), the town gets riled up at Sheriff Haller’s lack of progress and perceived ineptitude. By the end of the first act, Marty’s best friend Brady joins the body count. The discovery of the mangled corpse by Sheriff Haller (O’Quinn) is emotional and effective. Soon, a full-on vigilante mob is formed.

I believe it’s worth taking a moment to address a common complaint about this film and others of its era. As one critic puts it, “After three grisly deaths in a town the size of a postage stamp, you’d think the FBI would descend upon Tarker’s Mills like a tick on a june bug,” whatever that’s supposed to mean. The sad fact is that in 1976, the year in which the film is set, the term “serial killer” and the attendant concept were not widely adopted by law enforcement and were certainly not in use by the public or media. Only with the creation of the ViCAP system in 1985 was the FBI intrinsically tied to the investigation of serial murder. Additionally, without a common motive or method, it’s debatable as to whether a string of seemingly unrelated murders committed by a nebulous “maniac” constitue serial homicide. I’m not playing apologist here, but as I get older I notice more and more of this flawed understanding of history creeping into film criticism, especially films set in a time other than the year in which they were made.</rant>

What follows in the second act is a small town mystery, with Marty convincing his sister that a werewolf is on the prowl. They quickly bring Uncle Red into the investigation, though he is more than a little skeptical, comparing it to a Hardy Boys adventure. There are plenty of suspects, but the audience isn’t kept guessing for long, and I imagine most will have figured things out long before the reveal. Still, I’m not going to spoil the werewolf’s identity here. Thankfully, the trailer below keeps things mysterious as well.

Despite being based upon King’s novella, the Silver Bullet script went through a number of rewrites. Most notable is the initial plan for the werewolf to speak to demonstrate a retention of some of its human intelligence, but this was quickly scrapped. The werewolf demonstrated this trait in other ways, such as angrily beating a man to death with his own baseball bat. Gary Busey was also given license to ad lib in many of his takes. Stephen King and director Danial Attias liked some of them so much, they were kept for the final cut of the film.

The werewolf suit was designed by two-time Oscar winner Carlo Rambaldi (Alien, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, and many other genre classics). Producer Dino de Laurentiis was unimpressed and demanded changes that King and Rambaldi refused. With production looking to stall out, then-director Don Coscarelli (Phantasm, The Beastmaster) began filming the non-werewolf scenes. Eventually, with the werewolf debate still unresolved, Coscarelli quit and was replaced by Attias. Laurentiis was forced to capitulate rather than see the film shelved, but the modern dance actor hired to portray the werewolf still failed to pass muster and was replaced by the actor playing the werewolf’s alter ego, leading to credit for a dual role. I find that the disparity between the Coscarelli-helmed human scenes and the almost campy, old-fashioned, dry ice-obscured werewolf scenes plays to the strengths of both halves of the film.

Terry O’Quinn and Gary Busey aren’t the only actors bringing their A-games to supporting roles. Lawrence Tierney (Reservoir Dogs) is natural as the proprietor and bat-wielding regulator of Owen’s Bar. Everett McGill (Quest for Fire) gets one of his first big roles in this film as Reverend Lester Lowe. Bill Smitrovich (Splash) also gets plenty of lines as local loudmouth Andy Fairton.

Terry’s Subsequent Projects

Terry landed his first starring role in The Stepfather (1987) as the title creep. A low-budget thriller, the film did well enough to spawn two sequels and a remake, though Terry reprised the role only once, in Stepfather II. Terry O’Quinn was singled out for his performance in the original, earning nominations for both an Independent Spirit Award and a Saturn Award.

Terry found steady work in supporting roles on both television and in film, but he is perhaps best known for his breakthrough role as John Locke on the hit series Lost. Having worked with series creator J. J. Abrams previously on Alias, Locke was the only main character that did not have official auditions. After a seven-episode stint on The West Wing, Abrams called O’Quinn to get him on board the fateful Oceanic Flight 815. In 2007, Terry O’Quinn was recognized for his work by being awarded the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series.

From small roles to big, heroes, villains, and otherwise, Terry O’Quinn has ever been a consummate professional. His characters can make you believe in werewolves, Rocketeers, cowboys, and aliens because of his conviction as an actor.

Many thanks and best wishes always.

“Acting has to be your only alternative. You can’t go into it and have a fall-back profession waiting. If you only try halfway, you are going to fail. If you are jumping from one building to the next, do not slow down before you jump. Jump. Jump hard.” — Terry O’Quinn