The Peter Cushing Centennial Blogathon begins today, and WeirdFlix is proud to participate in honoring one of the most cherished actors of the 20th century.

Initiated by Frankensteinia (your one stop for all things Frankenstein), the Blogathon will celebrate the life and career of Peter Cushing with profiles, art, reviews, and anecdotes all around the blogosphere. Here at WeirdFlix, we’ll take a comprehensive look at Mr. Cushing’s career in film tomorrow on his birthday. We don’t want to leave you empty-handed on Day One, however, so we’ve got a little curiosity item for you below.

Watching weird movies and blogging about them are just two of my hobbies. If only I could add time travel to the list, I’d have enough time for all of them. I guess watching Doctor Who is about as close as I’ll get.

Here’s a short video of Peter Cushing enjoying one of his own hobbies:

Sadly, the end of the video is cut. Per British Pathé, it should say “…proving, if we needed proof, that playing soldiers is one game that we’ll never grow tired of.”

Much has been made of H.G. Wells’ full title, “Little Wars: a game for boys from twelve years of age to one hundred and fifty and for that more intelligent sort of girl who likes boys’ games and books”. I would contend that Wells didn’t mean for the “more intelligent” quip to be taken any more seriously than the notion that two 150-year-old men would crawl around on the floor playing his game. Indeed, the notion that a girl would even WANT to play a traditionally boys’ game is quite modern, and Wells even suggesting the possibility is pretty progressive for 1913.

I still engage in the occasional tabletop battle, but I’m not terribly skilled at painting the little buggers. I leave that to my lovely wife, who has made quite a career out of it. She does manage to “drag” me to Gen Con every year, and the very thought that I might have pushed my little army against that of Grand Moff Tarkin does indeed warm the heart.

As of this writing, Peter Cushing is one of the most referenced actors on this humble site, as represented by the big honking tag in the list to the right. If you’re reading this after May, 2013, that might have changed, but I have a gut feeling that with over a hundred screen credits to his name, many within the horror or science fiction genres, Mr. Cushing will be a frequent topic of discussion here.

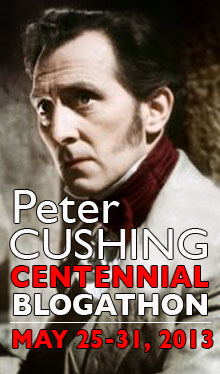

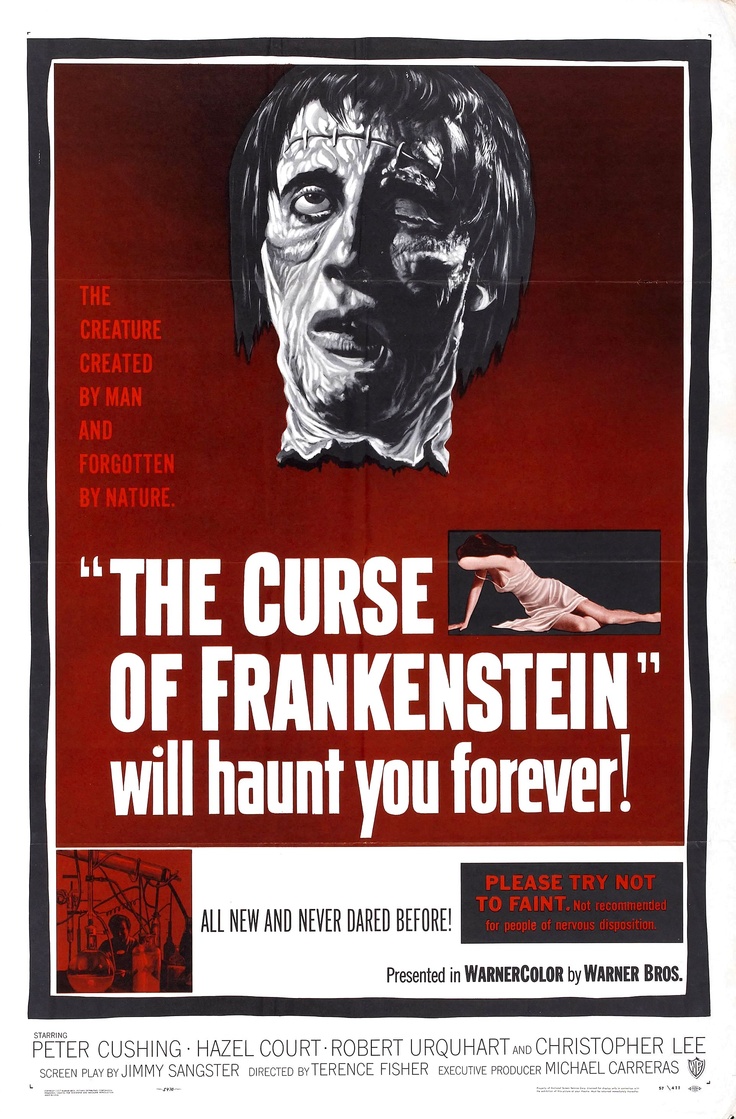

We first mentioned Cushing as part of our drinking game for At the Earth’s Core (1976), a fun if loose little adaptation of the Edgar Rice Burroughs novel. Kevin Connor had previously directed Cushing for Amicus Productions in the portmanteau horror film From Beyond the Grave (1973). Core is noteworthy for Cushing’s portrayal of the quintessential absent-minded professor, a role that is more whimsical than his usual intense scientists, vampire hunters, and detectives.

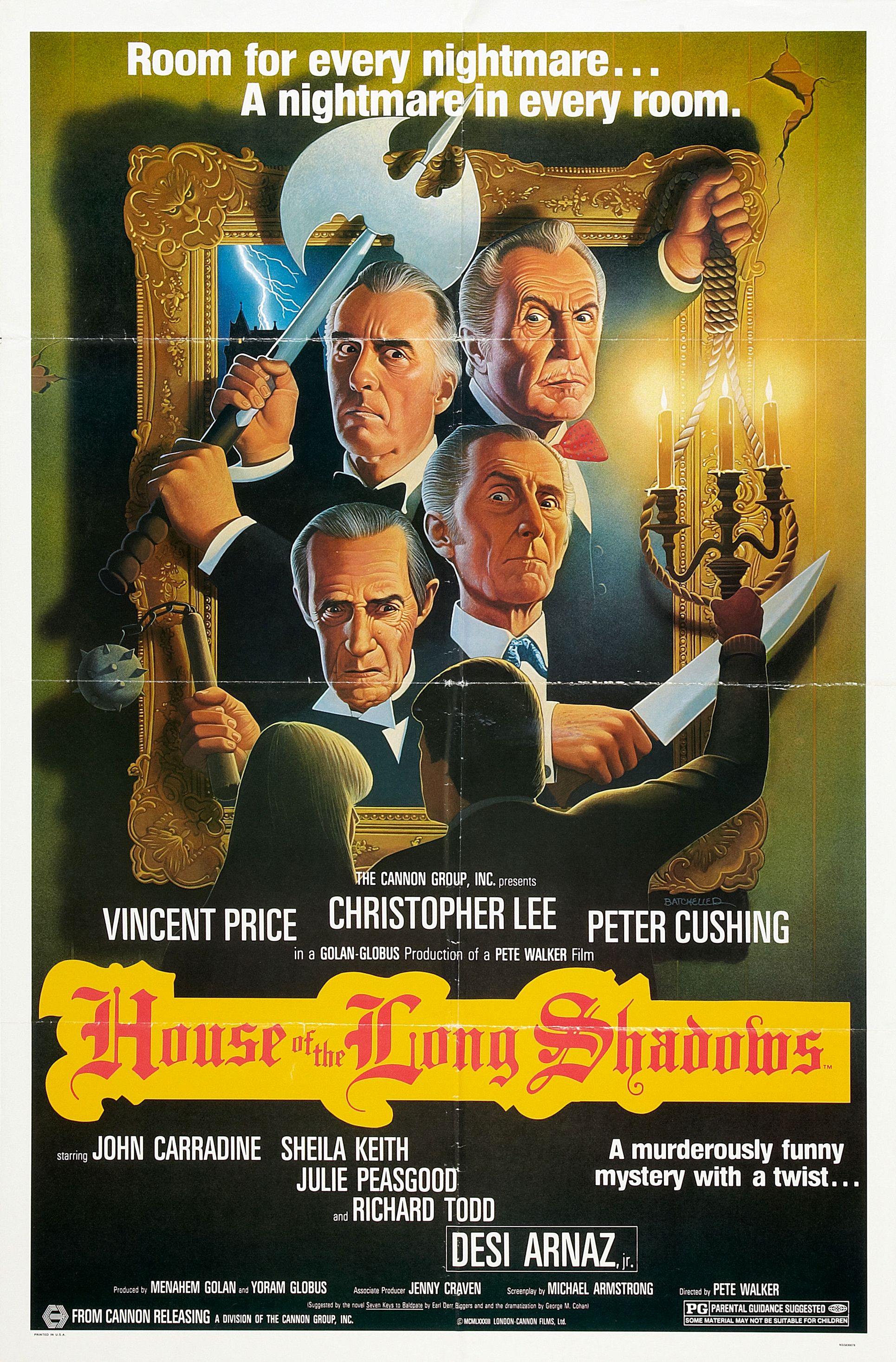

Another literary adaptation we previously examined is the Hammer Films treatment of She (1965). Peter plays the narrator of H. Rider Haggard’s novel, the Cambridge professor and amateur archaeologist, Horace Holly. Holly is a focused explorer and, as a former soldier, a man of action, so he’s a far cry from the absent-minded or bumbling professor archetypes. The film, as a whole, is a fun little adventure romp, and Cushing gets to play against his favorite foil and best friend, Christopher Lee as the devious high priest, Billali.

Earlier, I hinted at my long held affection for Doctor Who, both old and new. In our tribute to Dalek creator Terry Nation, we discussed the pair of Doctor Who feature films with Peter Cushing in a version of the title role. I say version, because this character isn’t the Time Lord seen in other versions, but a human professor whose surname is actually Who.

There is a lot of hand-wringing among science fiction fans about what constitutes “canon”. Lucas Licensing even maintains a continuity database, ranking various elements of the Star Wars Expanded Universe in different levels of canon. It strikes me as particularly absurd, then, that in a series that revolves around travel through space, time, and dimensions (the S, T, and D of TARDIS, respectively), that anyone would take a hard stance on Cushing’s Doctor not being “real”.

As writer Alan Moore so poignantly stated in his introduction to the Superman story, “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?”…

This is an IMAGINARY STORY… Aren’t they all?”

Please come back tomorrow when we’ll celebrate Mr. Cushing’s birthday by looking at his long and storied career in film. Thanks for visiting, and we hope to see you again soon!