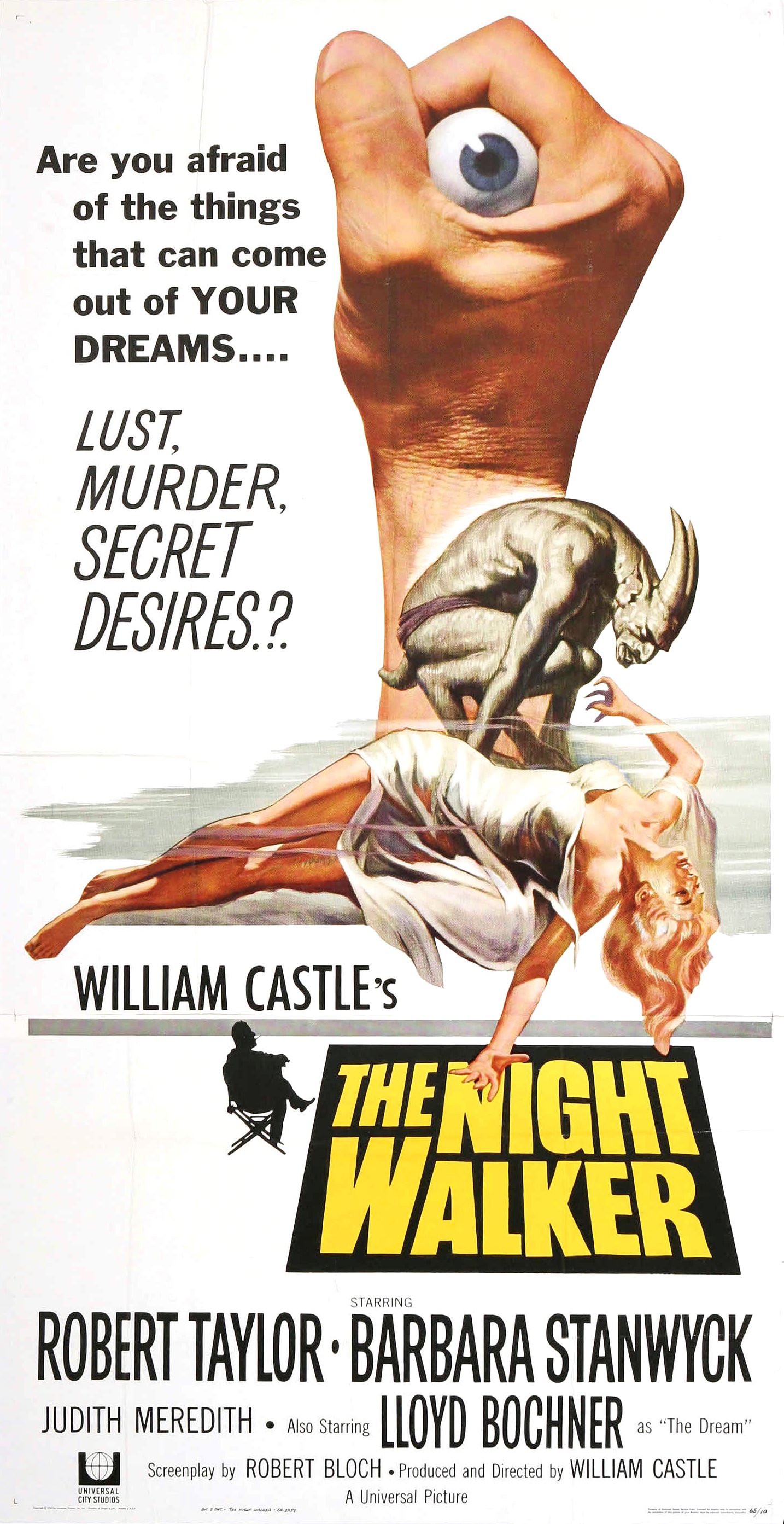

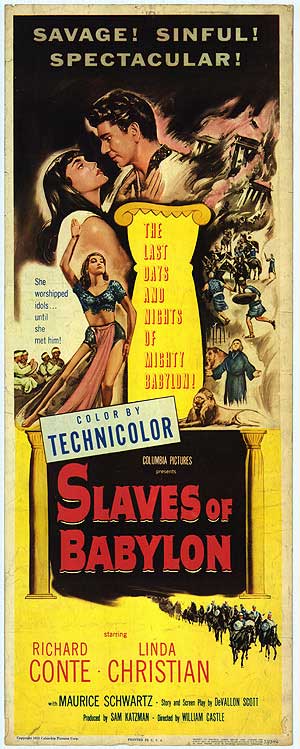

William Castle was born William Schloss, Jr. in New York City on this date in 1914. Schloss took the stage name Castle (translating “Schloss” from German to English) when he made his Broadway debut in 1922. At age 13, William was mesmerized by the Prince of Darkness himself, Dracula, played on Broadway by Bela Lugosi, just a few years before Bela reprised the role on film for Universal. On Lugosi’s recommendation, William Castle was given a job as an assistant stage manager, causing Castle to drop out of high school.

By 1941, Castle had acquired a knack for creative misrepresentation, having already posed as the nephew of famed Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn during his teenage years. With Orson Welles leaving his renowned Stony Creek Theatre in Connecticut to make Citizen Kane (1941), Castle seized upon the opportunity and convinced Welles to lease him the theater. Castle’s leading lady was the Berlin-born Ellen Schwanneke, but theater guild regulations dictated that German-born actors could only appear in plays originally performed in Germany. Castle responded by immediately conjuring up a fictional German play, Das ist nicht für Kinder (Not for Children). Ellen Schwanneke was invited to return to Germany by the Nazis, and this further fueled Castle’s hype machine. Promoting Schwanneke as “The Girl Who Said No to Hitler,” Castle used the telegram refusal as a press release of sorts. He even went so far as to secretly vandalize the outside of his own theater with swastikas to create additional controversy.

It was the first of what would become William Castle’s enduring legacy, promotional gimmicks that were often more memorable than the film they were designed to shill.

The Tingler (1959)

The gimmick at work in William Castle’s The Tingler is Percepto, a 4D film experience provided by $250,000 worth of surplus WWII airplane wing deicing motors. These were affixed to the undersides of seats scattered throughout the theater. At an appropriate moment in the film’s climactic sequence, the screen would go black and these motors would buzz, eliciting screams from startled patrons in the gimmicked seats.

The Tingler is the third of five collaborations between screenwriter Robb White and director/producer William Castle, following Macabre (1958) and House on Haunted Hill (1959). White was a world traveler, a pilot in WWII, and a prolific writer, leaving his engineering job with DuPont after selling his first story for $100. Of his 24 published novels, only one remains in print, the Edgar Award-winning Deathwatch (adapted for ABC television in 1974 as Savages).

So, what is a “Tingler?” Well, according to Dr. Warren Chapin (Vincent Price), the Tingler is a parasite that lives at the base of the human spine, feeding upon fear. If it grows too large, unabated, it will eventually crush your vertebrae, providing a physical justification for death by fright. Screaming relieves some of this tension and causes the creature to relent. This is, admittedly, questionable science at best, and probably more appropriate to a Frankenstein film set in the Victorian era than in the late 1950s, but we’re not exactly talking Watch Mr. Wizard here. This is just a couple years after The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) proposed that the heart is composed of one big cell. I guess movie-goers weren’t exactly up on grade school anatomy back then or they just cared a lot less about such inaccuracies.

For a film with such a hokey sci-fi premise, The Tingler manages to pack in quite a bit of subtext without being preachy or ham-handed. The most obvious juxtaposition in the film is the thin veil between the rational and the irrational, a line easily blurred by drugs, madness, or both. When Chapin is stymied by his inability to frighten himself, he resorts to LSD, providing the first depiction of acid use in a major motion picture. The resulting experience is surprisingly restrained, largely conveyed by the often underrated acting talent of Vincent Price. One can only imagine the gonzo directorial choices of a Dario Argento, Terry Gilliam, or David Lynch.

A particularly stylish demonstration of the irrational is accomplished by filming one of the signature scenes in color. A bathtub filled with garish red blood sits in striking contrast to a set painted in gray tones and an actress covered in ashen make-up to match. The visual effect is surprisingly seamless.

This use of color also highlights another of the movie’s main themes, that of changes in the film industry itself. Oliver and Martha Higgins (Philip Coolidge and Judith Evelyn) are the owners of a struggling revival theatre that shows silent films. Oliver seems to speak from William Castle’s own heart when he pines that “Some of these old silents are just as good as the movies they make nowadays even though the sound and the color and the screen’s a block wide.”

Chapin’s source of wealth involves another of the film’s themes, that of class divide. Chapin’s laboratory and research are funded by his father-in-law, as his unfaithful wife, Isabel (Patricia Cutts), is all to quick to remind him. Isabel cuckolds him with a heartless bravado more commonly seen in film noir. Cutts is delightfully vampish as the spoiled daddy’s girl. Check her out in the lusciously lurid red dress to the left.

Pamela Lincoln and Darryl Hickman round out the cast as Lucy Stevens and David Morris, Chapin’s sister-in-law and research partner, respectively. An accomplished child actor, Hickman had well over a hundred credits to his name before being recruited by Castle to play Lucy’s fiancé in the film. Reluctant at first, Hickman was convinced by Castle that it would help his real life fiancé’s career. Darryl even declined his salary for the role. Sharing scenes as a fellow pathologist alongside Price’s Dr. Chapin, Hickman was forced to wear lifts to bridge the gap between his 5’10″ height and Vincent Price’s towering 6’4″ frame.

The climax of the film takes place in the revival theatre, during a surprisingly packed showing of the silent film Tol’able David (1921). This provides a great opportunity for the film to build suspense without dialogue while the tingler makes its way through the unsuspecting audience in search of a prospective victim. The film comes close to breaking the fourth wall as the screen goes black when Dr. Chapin cuts the power. For theatrical premieres, a fainting woman (in actuality a planted shill) is taken out of the audience on a stretcher. After some verbal reassurances from Chapin to the in-film audience (which serves double duty as Price reassuring the “real world” audience), our film resumes for the grand finale.

The Percepto gimmick made quite the impression on many theater-goers. In his youth, cult film director John Waters would seek out a rigged seat to get the full effect while viewing. “Rumble-Rama” in the film Matinee (1993) and the character of Lawrence Woolsey (John Goodman) are clearly based on Castle and his ambitious promotional style.

Even without the dubious benefits of Percepto, The Tingler is a fun little monster movie, well worth your time. For this and his many other contributions to genre film, we give heartfelt thanks to William Castle. He was certainly one of a kind.